This summer I spent six weeks working in the University of Surrey Archives & Special Collections department assisting with completion of several projects which, for the most part, are the culmination of previous projects undertaken by volunteers to the archive, all of whom have given generously of their time and have contributed additional knowledge specific to individual objects in the collections. Their work and invaluable additional information animates far more readily the data for anyone coming into contact with the Archives catalogue at Surrey.

Working alongside the Archivist (Collections Management) and the rest of the team, I assisted with the completion of several summer projects. Projects undertaken:

E H Shepard Archive: World War I Correspondence from Florence Shepard to E H Shepard

Battersea Polytechnic and University Training Restaurant Silverware Catalogue: Data Transfer

Posters Audit and Condition Check

Battersea Polytechnic Photographs Audit and Data Transfer

Strong Room Audit

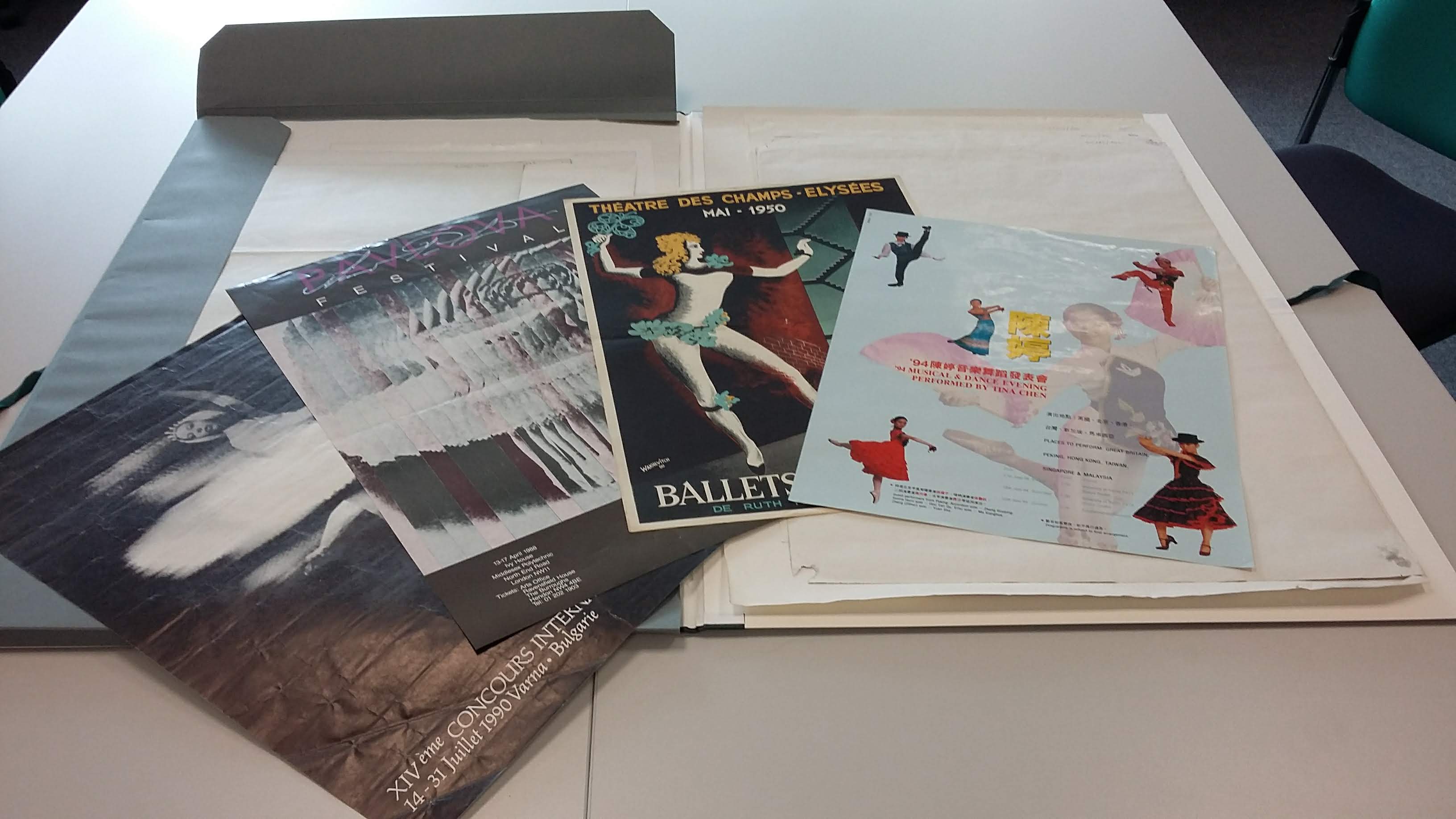

As individual works of art in their own right, the historical posters from collections held in University of Surrey’s Archives & Special Collections department, document performances of major dance companies throughout the 20th century, and showcases the distinct artistic oeuvre of each company. During my preparatory introduction to audit and condition check these incredible objects, it struck me how the data relating to each item far belies its intrinsic worth and encyclopaedic cultural value. Bound up and injected into each of these predominantly photographic images, we witness a multiplicity of professionals’ crafting and artistic input, which in turn requires the care of archivists, conservators, curators, and specialist librarians to make available such artefacts to increasingly wider audiences. Not only do such visual material cultural objects enrich our social and historical knowledge of each dance company, but in so doing they grow their archives exponentially.

This led to my thinking, not only about the objects/artefacts held at the heart of these collections, but also their intended audiences and who they might be, the networks as it were, who enter the archives to interact with these objects. Included in this evaluation is the time required and invested to make objects of a collection readily available and accessible. I do not mean monetary values, but rather, the value placed upon them as cultural and sociohistorical objects.

When I think about the archive I tend to think visually, and I wanted to see where connections occur. Two terms which really stood out for me: object or artefact, inanimate under the appreciative gaze of our research and exploration, but subsequently reanimated by its intellectual force; and network, an audience who participate in and are part of its network, and who produce, view, conserve, and produce networks enlivened by their interaction with these objects. This most crucial aspect provides a conceptual apparatus wherein the object is reanimated by continual audience interaction through a network of those whose time, professionalism and, for want of a better phrase, man-hours, amplify an object’s value. In other words, if we take one of the posters as an example, we see represented the additional value of the craftsmanship of each photographer or artist. Each is at pains to convey something of themselves alongside the artistic vision they aim to project to the intended audience.

Posters under the umbrella of the National Resource Centre for Dance (NRCD) collection, include collection strands such as Rambert Dance Company and Harlequin Ballet. During the period from 1940s-2000s Rambert Ballet posters displayed images of dances or performances from their twice yearly shows at Sadler’s Wells, but we know from other sources that post 2007 these images were more focussed upon specific dancers, rather than specific works – photographic output is politicised and yet more informational. Injected into these images we have not only a snapshot of a show, but also an insight into the careers of many artists. Although the value of objects are subjective, they have the power to hold onto traces of all these individuals.

The experience and journeys – professional, academic, and non-professional – of these artists and all whom facilitated or crossed their paths, become implicated in ventures with these dance companies, and are made visible by the objects. Added to this and invested in these objects, we not only have the years of challenge it has taken the professional dancers, musicians, costumiers, lighting, stage scenery and management, to hone their craft, but also the input from their respective tutors. All these invaluable crafts and skills merge into the productive process needed for each poster. The archive provides both repository and conditions to preserve the object, and also a stage/platform from which to generate new conversations and ways of approaching or thinking about them. By our interaction, we reanimate the cultural values manifest in these objects. Inanimate they may be, but they are not dead to us and, I would like to suggest, they are there to be reinvigorated, reimagined, and used to inspire future individuals to produce new responses in their learning and/or enjoyment of these objects.

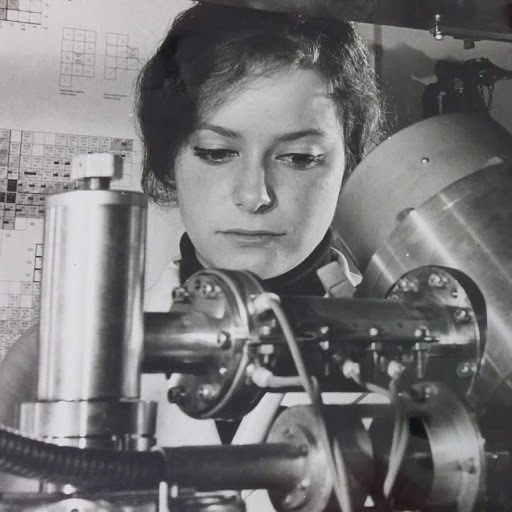

Photograph of Chemistry student Lesley Paneth in a laboratory at Battersea College of Technology using a Mass Spectrometer, 1960s. Photographer unknown. Ref. No. BA/PH/2/1/2

Among the networks which participate in preservation and documenting these objects are the ongoing volunteer projects which led to my assisting with the summer projects of 2018. Battersea Photographs Audit and Data Transfer involved 100s of photographs which document the historic transitory pathway of Battersea Polytechnic up until 1956/7, when it became Battersea College of Technology (1957), and finally to its current incarnation as the University of Surrey. The photographs, and some of the more fragile posters, had been placed individually into protective polyester film sleeves. Each had any supplementary information found on the reverse entered into CALM Surrey’s archive management system, in preparation for my editing and transcription.

Another of the summer projects was to transfer meticulous summary records of letters found in the E H Shepard Archive; these were some of the letters written from E H Shepard’s first wife, Florence, to him during World War I. Again, invaluable work was initially undertaken by a volunteer, an MA student on a short placement (blog post https://blogs.surrey.ac.uk/archives/2018/02/21/a-new-recruit-to-the-archives-team-and-a-whole-lot-of-letters-to-read/). I had the great pleasure and privilege of transferring this data into CALM, so that researchers, and all those wishing to explore the catalogue, immediately have a clear idea of what each letter contains. I must confess that as with all the exquisite collections held in the archive, it is easy to become lost in, and transfixed by, these historical artefacts which have so much to tell.

This is also true of even the simplest of tasks I undertook during my time in the archives, such as measuring up books of historical records held for Battersea Polytechnic, Battersea College of Technology, etc to be housed in new protective boxes. You can see evidence of the quality of booking binding in each record. Another case in point involved auditing the strong room while updating records to check locations of items in the collections. It was incredibly easy and hugely pleasurable to disappear down a (research) rabbit warren, as it were, to read the press cuttings and pamphlets (1970s) relating to a Japanese Kabuki Theatre and Dance company, which I myself had seen in their most recent incarnation – now several generations on, but from the same theatrical family. And as for the Farrar Collection…

Marbled paper used in bookkeeping records for Battersea Polytechnic and Battersea College of Technology

Working on transcribing, editing, and data transfer of information relating to “Training Restaurant Silverware Catalogue: Data Transfer”, was a particular highlight of my time in the archives, along with meeting the alumni researcher and volunteer, who had originally undertaken this project. These aesthetically pleasing objects are variously, and sometimes incorrectly, referred to as the “Surrey Silver”. Each piece is electroplated nickel silver and some bear the inscription of Mappin & Webb, and came from Battersea to the University of Surrey to be used in the training restaurant. Each piece has been carefully itemised, wrapped and boxed, but it is all the supplementary information supplied by the volunteer about these objects which is so invaluable. Historical specificity relaying to us how these training objects were used, who used them as a teaching aide and who trained using them, becomes interwoven with the object and its social history.

This therefore, is not only our history, but an historical representation of high-end dining out in the first half of the 20th century, which in turn directs us to the social history of female emancipation and the crisis in domestic service post WWI. The added value of this knowledge, and of each man-hour invested in the creation of an object’s history, is key to our understanding of how it is experienced by student, lecturer and everyone else who comes into contact with each individual object. These networks of knowledge accompany each poster, photograph, and piece of training silverware, and experienced in this light, the object becomes a cultural interface, a point of valuable interchange where knowledge can be exchanged. Objects are the central purpose of an archive and each object is not an ending, but a new beginning of discovery, research, and development of the archives and its networks. We are the network.

I shall presently have the pleasure of interviewing the alumni researcher and volunteer who gave so much of her time and her invaluable knowledge. This will appear in a further blogpost from University of Surrey Archives & Special Collections.