By Diane Watt, University of Surrey

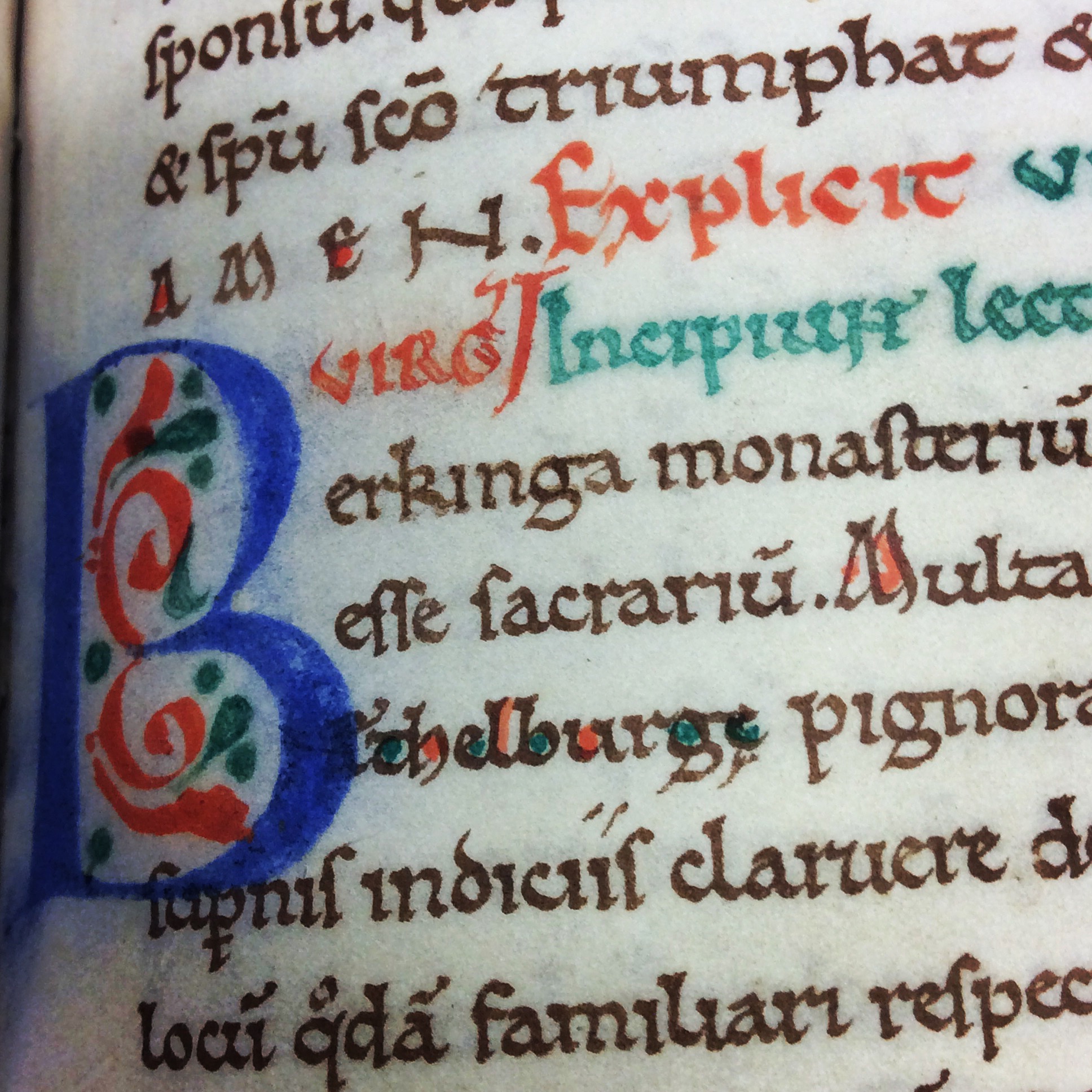

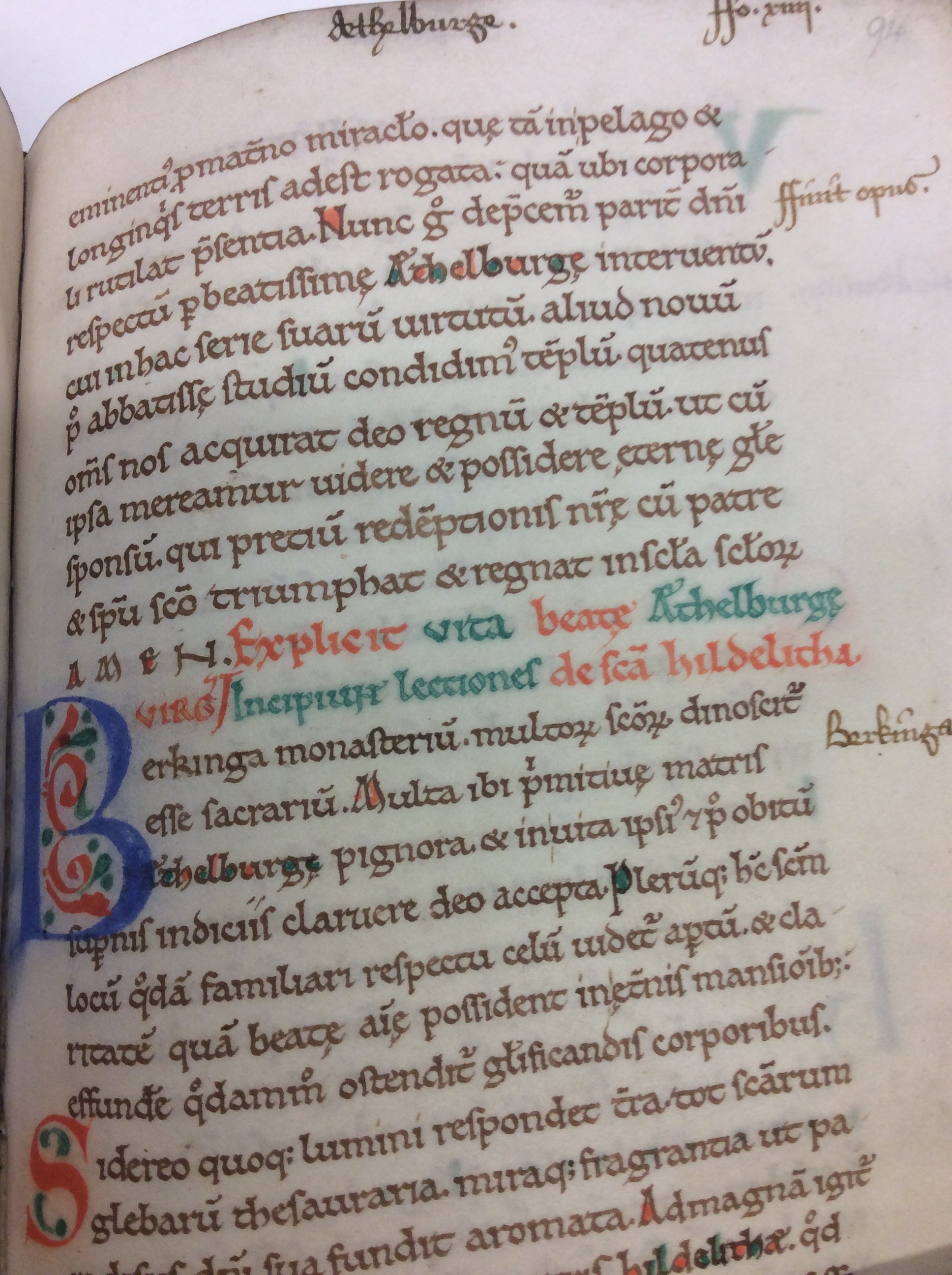

Cardiff, Central Library, MS 1.381, fol.94r. Decorated initial marking the beginning of the lections for St Hildelith (c) Diane Watt.

In Cardiff, Central Library, MS 1.381, a life of the fifth-sixth century Breton saint Winwaloe, abbot of Landévennec (fols.1r-80v) is bound together with a collection of lives of the saints (fols.81r-146r), containing seven items. The first is a Life of Æthelburh (fols.84r-94r), written in the late eleventh century by Goscelin of St Bertin and commissioned by the nuns of Barking, which is followed by lections for St Hildelith (fols.94r-96v), the Life of Edward, King and Martyr (fols.97r-102v), a Life of Edith of Wilton, also by Goscelin (fols.102v-120r), a Life of St David (fols.121r-129v), a metrical Life of Mary of Egypt (fols.130r-135v) and a Life of the Frankish hermit saint Ebrulf (136r-146r).

Dating to the first half of the twelfth century, some of the contents of the collection of saints’ lives in Cardiff, Central Library MS 1.381 indicate that this was a manuscript for nuns. In his Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries II, Abbotsford-Keele (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), N.R. Ker contends that the first two items (the life of their founding abbess Æthelburh and lections for her successor St Hildelith), may have been copied for or at Barking Abbey and that all the items, including the life of Edith, were foliated at Barking Abbey around the end of the fifteenth-century or beginning of the sixteenth (348-49). Ker also suggests that the Barking nuns were responsible for the marginal annotations that run through the collection.

Cardiff, Central Library, MS 1.381, fol.94r. ‘Berkinga’ or ‘Barking’ appears as a marginal annotation at the beginning of the lections for St Hildelith (c) Diane Watt.

While the assorted lives in this collection are fairly eclectic, one immediately striking inclusion is the Life of Edward, King and Martyr, a version of a text that may have been authored by a nun of Shaftesbury, or at any rate was produced for the convent. Edward was the half-brother of Edith of Wilton and this life is in the same hand as the life of Edith. Furthermore, the narrative of Mary of Egypt, with its account of the desert mother’s devotion to the Virgin Mary, is one that may have appealed particularly to women.

It is, however, the presence of Goscelin’s histories of Æthelburh, Hildelith and Edith that is most indicative of a strong female interest in this manuscript. The former text, along with Goscelin’s other Barking works (with the exception of the Hildelith lessons) is also found in Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS 176, which Marvin L. Colker unsurprisingly thinks may also be a Barking manuscript, although there is no additional evidence to support this (‘Texts of Jocelyn of Canterbury’, Studia Monastica 7 (1965), p.393). Goscelin (c.1035-after 1107), was a highly skilled writer who was in high demand amongst the religious communities of the South of England, including the important houses of women at Wilton and Barking.

The Life of Edith is the first part of the larger Legend, which was composed by Goscelin in the late 1070s. The second part is the Translation of Edith, which focuses on posthumous events and miracles. Commissioned by the Wilton community, the Legend draws heavily on the testimony of the nuns and on oral records passed down through the generations. Goscelin also worked from materials he consulted in the Wilton library, including now lost texts authored by the nuns themselves. The Barking lives were written a decade or so later, and an important source for Goscelin in their production was the nun Judith, whose memories informed some of his accounts.

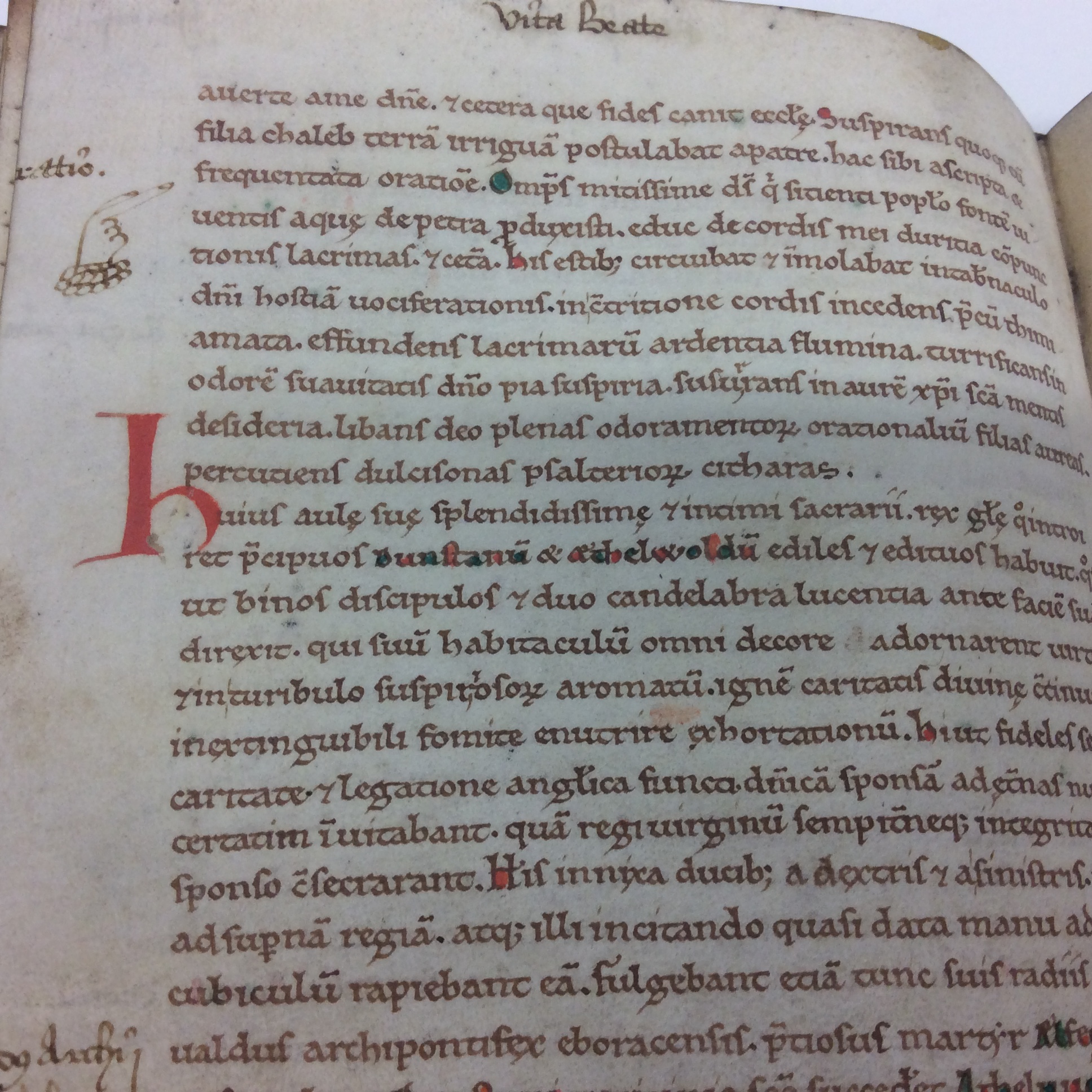

The Life of Edith that appears in Cardiff, Central Library MS 1.381 is particularly important because it is the earliest surviving version of that text. Edith (961-984), daughter of King Edgar and Wulfthryth, abbess of Wilton, seems a somewhat unlikely model of sanctity. According to Goscelin’s account, rather than confine herself to the simple habit of a nun, she sometimes arrayed herself in regal dress, and she also maintained a private zoo within Wilton for her own enjoyment. Yet despite such controversial behaviour, her memory was cherished by the nuns. The chapel she had built at Wilton was remembered long after it had been replaced, a book of prayers copied in her own hand was preserved as a relic, and, of course, her story was revived by one of the most important monastic hagiographers of the age.

The texts that comprise the Legend survive in two other manuscripts alongside Cardiff. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson C.938, dates to the thirteenth-century, and contains both the Life (fols. 1r-16v) and Translation (fols. 16r-29v) and probably represents the text in its original form. There is also another text of the Legend which follows the version found in Rawlinson, but with some additional changes and without the metrical sections. It appears in a large collection of British saints (including the Barking saints and indeed the Life of Edward, mentioned above, inter alia) in the an early fourteenth-century manuscript of English provenance: Gotha, Forschungsbibliothek, Codex Memb. I.81, fols.188v-203r. The version of Goscelin’s Life found in the Cardiff manuscript, although earlier than Rawlinson, seems to incorporate substantial and substantive authorial revisions. Indeed it is likely that this version was actually adapted by Goscelin for the use of the nuns of Wilton.

Stephanie Hollis has summarised the main changes Goscelin made to the text in the Cardiff Life (‘Goscelin’s Writing and the Wilton Women’, 238-244).The Cardiff text of the Life excludes the original prologue but develops other aspects. It emphasizes Edith’s position within an élite female genealogy, expanding on the significance of Wulthfryth, who was of course greatly revered by the Wilton community, as an exemplar for Edith. The Cardiff manuscript also has a specificity that may be derived from local knowledge, identifying, for example, the location of the zoo within the building. It is striking that one the Barking nuns’ annotations to Edith’s Life in the Cardiff manuscript is the insertion of a manicule that directs the readers to the prayers in the added passage concerning Edith’s devotional manual that was so valued by her successors (fol.106v).

Cardiff, Central Library, MS 1.381, fol.106v. A marginal annotation and manicule directs the reader to the prayers of the saint in Goscelin’s Life of Edith (c) Diane Watt.

Other annotations to this manuscript highlight female figures, such as a comparison of the nuns to Christian Amazons (fol.107r) and another between Edith and Martha and Mary (fol.107v).

In his Legend, Goscelin records the history of the Wilton community even as he rewrites it, representing Edith as an idealised example of female monastic spirituality inspired in turn by her familial predecessors. Goscelin recognised the appeal of Edith’s story, or his version of it, to a female audience. A few years after he had completed the Legend, Goscelin composed the Liber confortatorius, addressed to Eve, a young recluse formerly of Wilton (c.1058-c.1125). There are some clear connections between the Cardiff manuscript and this subsequent work. A series of additions to the Cardiff text anticipate the apocalyptic representation of Edith as the mystical bride of Christ found in the Liber confortatorius. Hollis even goes so far as to suggest that the Cardiff manuscript ‘was a version intended for Eve … as well as for the Wilton community’ (Hollis, ‘Goscelin’s Writing and the Wilton Women’, 244).

To sum up, the Cardiff manuscript includes a version of Edith’s Life that was commissioned by a community of nuns in commemoration of one of their predecessors, and was subsequently adapted by its author for their use and to reflect their own interests.The connections between the Cardiff Life and the Liber confortatorius indicate that Goscelin may have assumed his addressee, Eve, was already familiar with the former text. Furthermore the manuscript reveals that Edith’s life was considered to be of sufficient importance to be incorporated within a collection of saints’ lives that was in the possession of Barking Abbey by the fifteenth century and that included Goscelin’s life of their own founding abbess. Indeed some of the Barking nuns’ annotations provide tantalising indications of specific areas of interest. The Cardiff manuscript is then testimony to the interest later generations of women readers had in Edith’s story.

Author’s Note: I am grateful to the Sir David Hughes Parry Award scheme (which funds work on topics of Welsh significance) for supporting my initial research on Cardiff, Central Library, MS 1.381. Further research in Cardiff, Dublin and Oxford was undertaken as part of my Leverhulme Trust Major Research Fellowship. Cornelia Hopf of the Forschungsbibliothek Gotha has kindly answered my queries about the Gotha manuscript. All errors are, of course, my own.