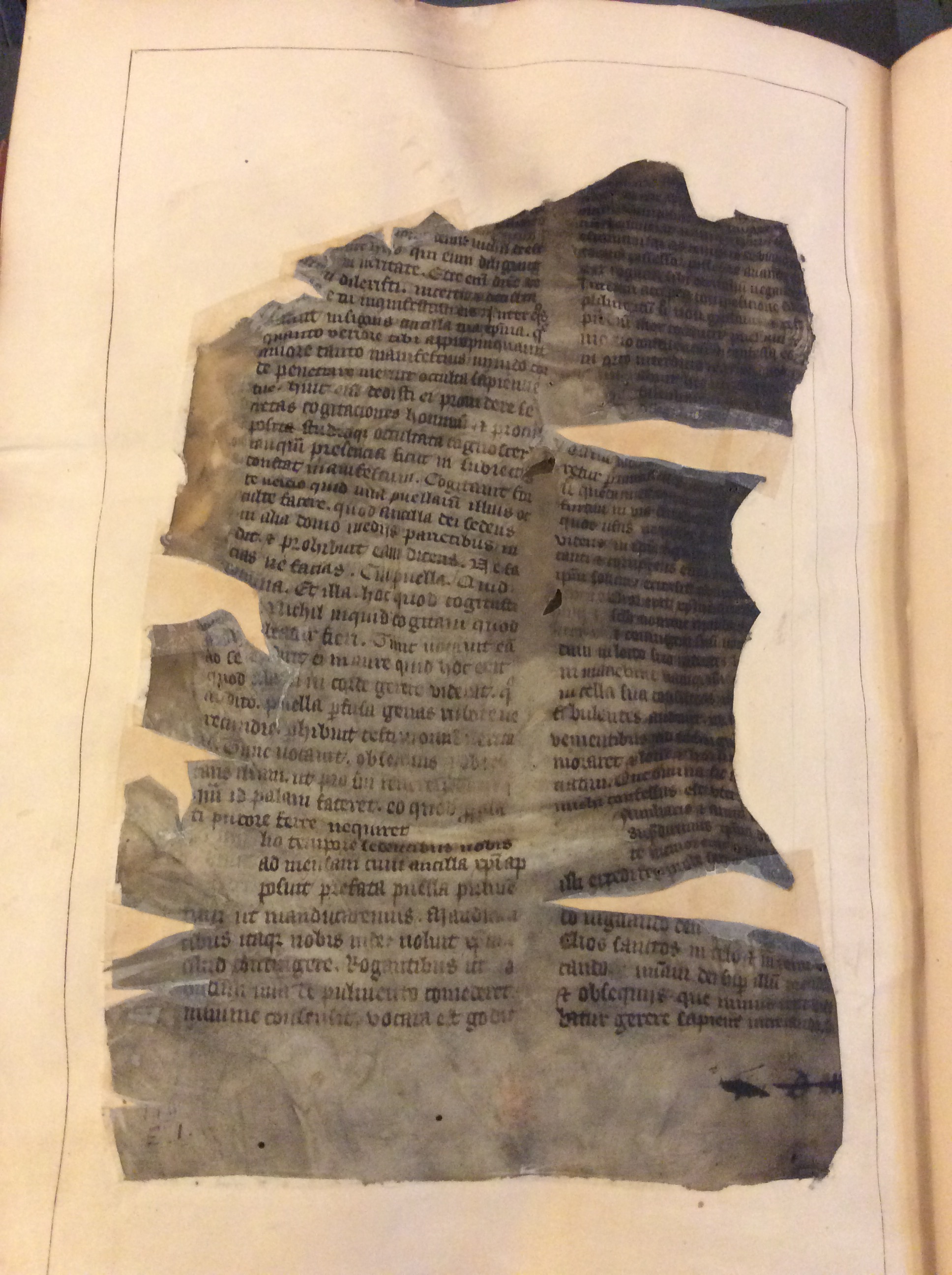

© British Library Board. London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius E.I, volume 2, fol. 167v.

© British Library Board. London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius E.I, volume 2, fol. 167v.

by Diane Watt

One of the challenges of the project ‘Women’s Literary Culture Before the Conquest’ is that many manuscripts related to early medieval women are scattered across Britain and Europe, and some are found even further afield. Books that once were owned by a single individual, a family, or a community, if they have survived at all, are often widely dispersed, and their present condition varies greatly. This is the case also with works from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the very end of the period that I am studying. A case in point is that of the manuscripts associated with the twelfth-century holy woman and prioress, Christina of Markyate (c.1096-after 1155).

Two major works are associated with Christina and her community at Markyate, which was a dependant priory of Abbey of St Albans, an important centre of manuscript production. The first is The Life of Christina of Markyate. This text was written, probably in the 1130s or 1140s, by an anonymous monk of St Albans whom Katie Bugyis has recently identified as Robert de Gorron, and who was to become abbot of St Albans from 1151 until his death in 1166 (‘The Author of the Life of Christina of Markyate’). Robert was the nephew of Geoffrey de Gorran, abbot of St Albans from 1119 to 1146, Christina’s chief supporter and patron. Geoffrey almost certainly commissioned the writing of The Life.

The Life in its most complete form is attested to in only one manuscript, London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius E.I, volume 2, fols. 145r–167v. The Tiberius manuscript, which is of English provenance, dates to the second half of the fourteenth century, and was once owned by Thomas de la Mare, abbot of St Albans from 1349 until 1396. Within the manuscript, The Life appears at the very end of the Sanctilogium Anglie, a fourteenth- century encyclopaedic collection of Latin hagiographies of British saints from before and after the Conquest compiled by the chronicler John of Tynemouth who may also have been a monk of St Albans. The Life is the last item in the manuscript, and it begins on a new folio and was copied by a different scribe.

The Sanctilogium Anglie was to prove a popular text. It was, for example, adapted to become the De sanctis Anglie and the Nova Legenda Anglie (the latter was misattributed to John Capgrave, and subsequently printed by Richard Pynson in the early sixteenth-century), but these later versions did not include the additional Life of Christina of Markyate.

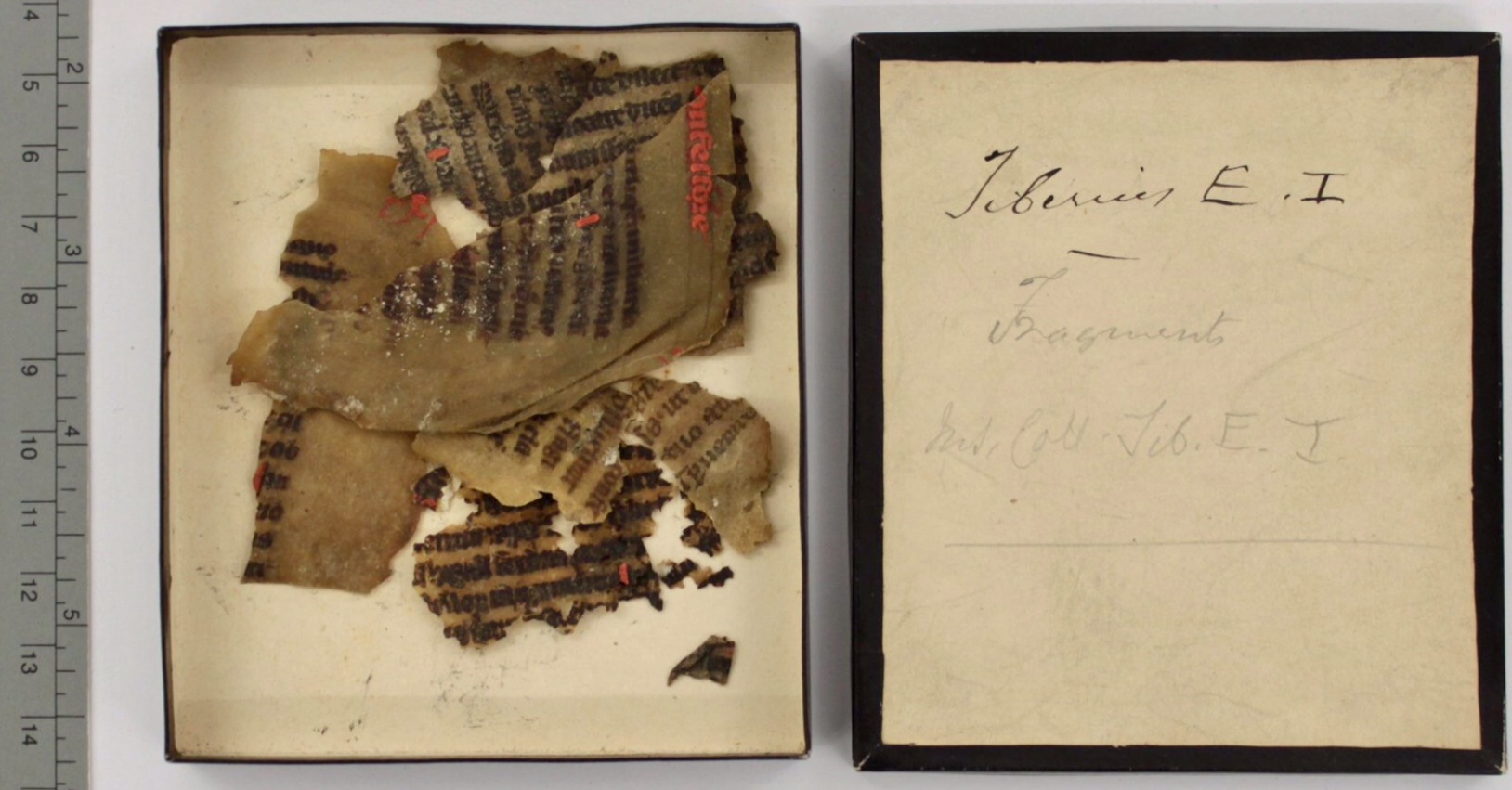

The Tiberius manuscript, containing as it did the only surviving copy of Christina’s Life, was very nearly destroyed by the fire that devastated the Cotton collection in the eighteenth century. As is apparent from the image at the beginning of this post, the parchment is badly charred and the manuscript is clearly missing its final leaf. Nevertheless the full extent of the damage is unclear. Approximately eight pieces of parchment that are believed to have belonged to the manuscript were salvaged and are now preserved within one of the boxes catalogued as Cotton Fragments XXXII. These fragments are so fragile that viewing is prohibited.

© British Library Board. MS Cotton Fragments XXXII. Tiberius E.I Fragments.

Yet while The Life of Christina of Markyate is missing its ending, other evidence indicates that this cannot be attributed to fire damage alone. A century before the Cotton fire, the antiquarian Nicholas Roscarrock (c. 1548–1633) consulted the text in the Tiberius manuscript and produced a summarized account of the Life in his monumental (and paradoxically titled) ‘Briefe Regester or Alphabeticall Catalogue of such Saincts and sainte like persons as have graced our Island of Great Brittaine, Ireland and other British Iselands’ (c.1644): Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, MS Add. 3041, fols. 3r-402v (at fols. 123v-125r). A comparison between Roscarrock’s synopsis of Christina’s Life and the version in the Tiberius manuscript reveals that the manuscript was already incomplete at the time Roscarrock viewed it and that only a small amount of text was subsequently lost (see Nova Legenda Anglie, ed. Horstman, vol. 2, 532-537).

Extracts of the Life of Christina of Markyate also appear in another St Albans’ manuscript, London, British Library, MS Cotton Claudius E.IV, which dates to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth centuries. Like Cotton Tiberius E.I, Cotton Claudius E.IV is now bound in two volumes. The extracts of Christina’s Life are part of a continuation of Matthew Paris’s mid-thirteenth century Gesta abbatum monasterii Sancti Albani written by Thomas Walsingham in the late fourteenth century which is found in volumes 1-2, fols. 97v–321r. The extracts themselves appear in volume 1, fols.111v-113r. These sections differ slightly but significantly from the surviving Life and therefore attest to the existence of another copy of the Life, which has subsequently disappeared (Gesta abbatum, Vol. 1, ed. Riley, 98-105). They also refer directly to a copy (possibly their immediate source) held at Markyate Priory, where Christina was founding prioress (Gesta abbatum, Vol.1, ed. Riley, 104-105).

From this, we can deduce that at least two different versions of the Life were in circulation in the later Middle Ages and that, although the Life was a product of St Albans Abbey, at least one manuscript, as one would expect, was at some point located in Christina’s own community at Markyate.

The second work closely connected to Christina is the St Albans Psalter: Hildesheim, Dombibliothek, MS St Godehard 1. Unlike the Tiberius manuscript, this beautiful codex is very well preserved. The Psalter was produced in the twelfth century, so is roughly contemporaneous with the writing of Christina’s Life, but, as I have discussed more fully in an earlier post on this blog, art historians and critics continue to disagree about fundamental issues such as its exact date (usually located sometime between the 1120s and the 1150s), whether it was intended for personal or communal use, whether it was planned as a single codex or is a composite manuscript, and whether it was even produced at St Albans Abbey.

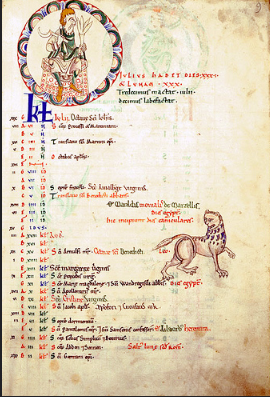

Even if we choose not to accept the argument (compelling though it is) that the Psalter was commissioned by Geoffrey de Gorran for Christina’s own use, it was clearly adapted for the Markyate community at some point. For example, it includes a Calendar that makes reference to the dedication of Markyate Priory in 1145, and notes the deaths of Christina and members of her family, and of both Geoffrey de Gorran and the hermit Roger with whom Christina had shared a cell before her profession as a nun. Bugyis identifies the scribe of the obits of Geoffrey, Christina and her family members as Robert de Gorran, the same monk who she believes wrote Christina’s Life (Bugyis, ‘Author’, 728-737).

St Albans Psalter Calendar, July, which includes Christina of Markyate’s obit. Hildesheim, Dombibliothek, MS St Godehard 1, p.9. Public Domain. Accessed 20 June 2018 from flickr

In addition, the St Albans Psalter calendar includes within it the feasts of three Anglo-Saxon women saints: Hild of Whitby (c. 614–680), Æthelthryth of Ely (d.679), and Frithuswith (Frideswide) of Oxford (c.680-727). These names are also written in the hand that Bugyis attributes to Robert de Gorran and are therefore part of the same supplementary scheme (Bugyis, ‘Author’, 728-737.) All three women were early founding abbesses and mothers of the English church, and, like Christina herself, two of them, Æthelthryth and Frithuswith struggled against the social and familial expectation that they should become wives. It is perfectly plausible that Christina and her community understood her life story in terms of this insular tradition of married women saints who sought to remain virgins and that is why their feasts were included on the Calendar for the use of the Markyate community.

Tantalizingly, the inclusion of these feast days in the St Albans Psalter Calendar also provides a further loose connection to the Tiberius manuscript. Latin hagiographies of a number of saintly women appear in the Sanctilogium Anglie, including, alongside an extensive list of other insular saints, male and female, Æthelthryth (volume 1, fols. 19r–20v), Frithuswith (volume 1, fols. 85v–87r), and Hild (volume 1, fols. 113v–115r), as well as that other important early English abbess, Æthelburh of Barking (d.686) (volume 1, fols. 79v–81r). Again, it would seem that Christina was viewed as part of a longer British tradition of sanctity. Likewise, the summary of Christina’s Life that Roscarrock includes within his collection locates it within a firmly insular tradition that harks back to the earliest history of the church and its founding mothers as well as fathers.

While scholarship on Christina and her books tends to focus on her Life and the St Albans Psalter, another psalter is also associated with Christina and her nuns. The St Albans Psalter provided the base text for a translation of the psalms from Latin into French prose that is found in the twelfth-century Oxford Psalter: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 320, fols. 37r-75v. In comparison to the St Albans Psalter, Douce 320 is only sparsely decorated. Ian Short, in the introduction to his recent edition of the Oxford Psalter (9-10), makes the case that Douce 320 was produced at St Albans specifically for the Markyate Priory around 1145, in other words at the time of its foundation. As Short points out, Douce 320 was copied by the same scribe responsible for many St Albans productions in this period, including Markyate Priory’s foundation charter. Taken together the two psalters reflect the multilingualism (Latin, English, and French) of the Markyate nuns and of women religious of the period more generally.

Yet another mid twelfth century psalter produced at St Albans, St Petersburg, National Library of Russia [formerly Leningrad, State Public Library] MS Q.v.I, 62, includes a Calendar with an entry for the saints Christina and Alexis. While I haven’t yet had the opportunity to view this manuscript either directly or in digital form, Rodney M. Thomson observes that within this entry the name Christina is partially erased (Manuscripts of St Albans Abbey, vol. 1, 37). This psalter does not have any direct links to Markyate itself and by the end of the twelfth century it had passed from St Albans into the possession of Wherwell Priory, a house of Benedictine nuns in Hampshire. Yet, as Rachel M. Koopmans points out in her essay, ‘The Conclusion to Christina of Markyate’s Vita’, while the Christina named in the Calendar could well be the more famous legendary virgin martyr of Tyre because connections do exist between the lives of St Alexis and Christina of Markyate it is perfectly plausibe that it is she who is referenced here (664-5), and that this entry provides additional evidence not only of an early cult of Christina, but also (with the erasure of Christina’s name) of its suppression.

The Life of Christina of Markyate and the St Albans Psalter together provide a particularly appropriate end point for my project, chronologically speaking, precisely because they connect back to earlier lives of saintly women, including the early Anglo-Saxon abbesses. But, looked at in the context of other manuscripts and texts, such as Roscarrock’s summary life, the extracts in the Gesta abbatum monasterii Sancti Albani, the Oxford Psalter, and the St Peterburg Calendar, they are also important because of what they reveal about, first, the uncertainties that continue to cloud our understanding of textual production and women’s book ownership in twelfth century, and, second, the scattered and fragile nature of much of the surviving evidence of women’s engagement with literary culture throughout the Middle Ages.