by Emily Butler, John Carroll University

In Anglo-Saxon England, the eleventh century was a time of great upheaval and political turmoil, with serious Viking raids, followed by a Danish conquest first in 1013 and more definitively in 1016, then the more famous Norman Conquest of 1066. One of the most important figures in the first half of the century was Emma of Normandy (d. 1052), and the text now known as the Encomium Emmae Reginae [In Praise of Queen Emma] offers a narrative of the Danish conquest and its aftermath, within an interpretive framework that places Emma herself at the centre of the story.

One of the most controversial aspects of the Encomium is the way that it departs from the accepted narrative of events, but when we remember that Emma not only commissioned the text, but was probably an important informant for the Encomiast (as the author of the text is known), these departures point to both the limitations and the opportunities for a widow trying to maintain a position of security at a deeply factionalized royal court.

Emma’s marriage to King Æthelred II in 1002 was the first foreign marriage of an English king since 856, and that fact prefigured Emma’s role at the heart of a web of international connections that was implicated in both of the eleventh-century conquests. As a nod to Æthelred’s saintly grandmother, Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury, Emma was known in England by the Anglo-Saxon name Ælfgifu. After the victory of the Danish Swein Forkbeard in 1013, the Anglo-Saxon royal family took refuge with Emma’s relatives in Normandy, until Swein’s death in 1014 opened the door for Æthelred to reclaim his throne. Following Æthelred’s own death in 1016, Swein’s son, Cnut, accomplished a second and more lasting Danish conquest at the Battle of Assandun.

Rather than being sidelined as the widow of the deceased king, whose successor had also been defeated, Emma married Cnut and became an important symbol of continuity with the former regime. It is not entirely clear how much agency Emma was able to exercise in the arrangements for this marriage. Whereas the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has her being ‘fetched’ to be Cnut’s wife, the Encomium later characterized the match as one for which Emma was wooed intensively and to which she agreed only on certain conditions.

Both of these sources should be taken with a grain of salt, and the truth may lie somewhere in the middle.

Nevertheless, perhaps as a result of her increased age and experience, as well as her status as a symbol of supposed continuity after the Danish Conquest, Emma seems to have played a more prominent role during the reign of Cnut than she did during the reign of Æthelred. It appears that she was still using the name Ælfgifu during Cnut’s reign, as can be seen in Stowe Charter 38, which claims that Cnut gave woodland to the Archbishop of Canterbury ‘at the request of his wife and queen, Ælfgyfe’ (petitione coniugis ac regine Ælfgyfe).

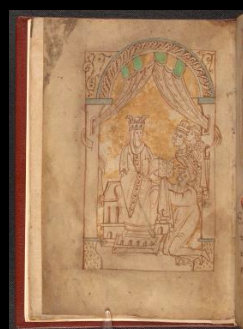

Cnut understood the power and potential significance of patronage in both Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon models. While he cultivated skaldic poetry at his court at Winchester, he also continued with the Anglo-Saxon tradition of ecclesiastical donation, as in Stowe Charter 38 or in this image that depicts Cnut and Emma (again referred to as Ælfgifu) as donors to New Minster at Winchester.

Stowe MS 944, f. 6 (c. 1031). Public domain.

After Cnut’s death in 1035, Emma was once again in a vulnerable position, with the succession in doubt and rival factions trying to advance the claims of different candidates. Emma took refuge in Flanders after a failed return from exile by her sons Edward and Alfred led to Alfred’s death. In 1040, Emma and Harthacnut (her son by Cnut) returned to England, and around 1041 or 1042, an anonymous Flemish monk completed the Encomium, apparently to shore up the delicate balance of power that saw Harthacnut and Edward sharing control of the country.

Much as Emma had spent her adult life navigating and interweaving different political and cultural identities, the Encomium drew on both Classical and Germanic traditions in order to present Emma as a peaceweaving figure whose presence at the royal court could unite different factions.

The text is written in Latin, rather than any of the vernaculars spoken by those at court, including English, Danish, French, Flemish, and perhaps even Welsh. While the choice to use Latin may look repressive, if we choose to view the linguistic history of the Middle Ages as a struggle between Latin and vernacular languages, the Encomium is a particularly clear example of a more constructive understanding of the linguistic dynamics of the period.

Rather than assuming a struggle or contest, it seems more accurate to say that there were situations when Latin was viewed as the more advantageous or prestigious language, as well as situations when a vernacular language was desirable for any of a number of reasons. In the Encomium, Latin is deployed as being the mother tongue of no one in the factionalized audience, for whom the memory of armed conflict must have been all too fresh.

For a more contemporary illustration of this principle, we might think of the way that English, even though it is associated with a former imperial regime, has gained a broad acceptance in India precisely because it does not represent the cultural heritage of any one region or ethnicity in the country.

The eleventh-century manuscript of the Encomium in the British Library is probably not the original, but it seems to be a close copy or relative. In the frontispiece of the manuscript, we can see Emma receiving the text from the anonymous Encomiast, while her sons Edward and Harthacnut (sons by Æthelred and Cnut, respectively) look on.

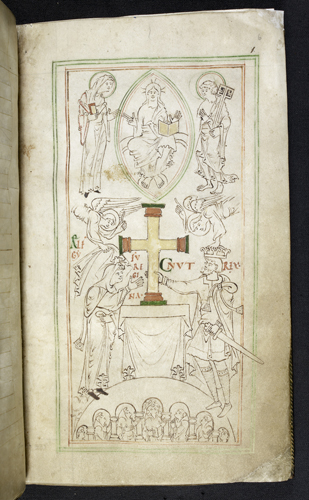

Additional MS 33241, f. 1v. Public domain.

This image of unity between mother and half-brothers may not have reflected reality, but it and the emphasis on such unity in the text of the Encomium tell us a lot about what Emma and others at court may have been concerned about in the late 1030s and early 1040s. In a sign of the apparent difficulty of her relationship with Edward, Emma’s property in Winchester was taken from her control towards the end of her life.

It might be tempting to see this ‘reduction in circumstances’ as an indication of an ultimate powerlessness or of a fundamental lack of influence or significance, but we can choose to learn instead from what Emma accomplished and what she endured in order to do so, in spite of the way that her family had been fractured by the effects of the Danish conquest.

Beyond what she did to try to ensure her sons’ succession, Emma served an equally important role as a model of patronage. It seems likely that Emma learned from what her mother, Gunnor, did as a patron of Norman historiography, encouraging the promulgation of an approved narrative of her deceased husband’s tenure as duke of Normandy. As a widow twice over, Emma seems to have used the Encomium in her efforts to see at least one of her surviving sons established on the throne, while securing for herself a stable position at court.

Although the actual text of the Encomium was composed by someone other than Emma herself, it reflects the concerns of a woman intimately familiar with the effects of conquest, the uncertainties of succession crises, and the dynamics of different language communities in close contact.

Shortly after the Norman Conquest, Emma’s daughter-in-law, Edith, herself a widow by that point, commissioned the Vita Ædwardi, ostensibly a Life of Edward the Confessor, son of Emma and Æthelred. (See Mary Dockray-Miller’s recent post on this blog). As with the Encomium, although Edward was the apparent focus (as Swein and Cnut had been prominent in the Encomium), the text seems to have been intended as a justification or support for Edith at a time when she was in a vulnerable position, as the widow of a king from the defeated regime.

There is no reason to believe that Emma and Edith collaborated on any text or other patronage project, but there is good reason to believe that Emma served as an important example of how a widow might leverage her seeming vulnerability into creative output and an assertion of her own status.