Guest post by Jessica Nina Lester (Indiana University, Bloomington) & Trena M. Paulus (Eastern Tennessee State University)

In November 2022, ChatGPT was released and became widely available to the public. Some researchers quickly moved to herald its potential in supporting research activities, while others urged caution. An increase in the speed and scale of research production has been positioned as a primary benefit of generative AI alongside an expansion of the ways in which research studies could be implemented.

Guest posts express the views of guest contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CAQDAS Networking Project or constitute an endorsement of any product, method or opinion.

Within the qualitative research community, scholars such as De Paoli have noted the near inevitability of generative AI adoption. Alongside this inevitability have come demonstrations of consistency between what generative AI can do and what human qualitative researchers produce. The leading CAQDAS companies have already integrated AI tools into their software. ATLAS.ti promotes its integration with ChatGPT as being able to “accelerate and customize” research. MAXQDA suggests that AI-assist can “automate your coding process” while functioning as a “virtual research assistant”. Even before ChatGPT was launched, proponents of large language models (LLMs), such as R. David Parker and colleagues, concluded that:

Generative AI and large language models are becoming the norm for analyzing large, complex data. As these tools require human intervention and interaction, qualitative researchers are natural partners to maximize context. The benefit to qualitative researchers is the significant cost and time savings as well as being on the cutting edge of emerging technology which is revolutionizing many fields.

This may very well be the case.

Yet, we wonder what the cost of being “on the cutting edge” might be. What are the seen and as yet unseen consequences of the move towards AI?

This question arises whenever new technologies are created and offered as solutions to particular societal problems. It’s critical, however, not to let the creators of these “technological solutions” be the only ones providing answers. Even now, over two years later, it remains extraordinarily difficult for even experienced researchers to determine the best path forward. What about AI is hype? What is useful? What is ethical?

As a starting point, we offer a reflexivity framework for qualitative researchers to consider the positive and negative, intended and unintended consequences of, as Ethan Mollick suggests, “inviting AI to the table”. As Fielding and Lee noted in 2008, “new technologies come with strings attached” (p. 491), interrogating those “strings” should be part of our digital research workflows.

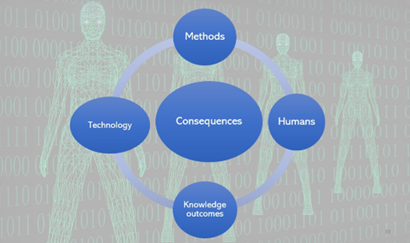

As illustrated in the figure below, we propose four categories (methods, technologies, humans, and knowledge) in which to consider the consequences of AI-assisted workflows and four guiding questions to support reflexivity.

| Questions to Engage in Technological Reflexivity |

| In what ways might existing methodologies and methods need to be adapted when using generative AI in a qualitative research workflow? |

| In what ways might existing AI technologies need to be re-designed or adapted in a way that makes ethical and trustworthy qualitative research possible? |

| What are the potential consequences that humans (both researchers and participants) might experience as they enact a research workflow that includes generative AI? |

| How will generative AI impact the types of knowledge we can produce? |

In the remaining sections we offer a few possible answers.

Consequences for qualitative methods

Generative AI has most certainly afforded new ways to think about doing qualitative research; most often as a speedy and more efficient process grounded in post-positivist paradigms. For some qualitative researchers, AI is described as being a ‘thinking partner’ or ‘assistant’. The strengths of generative AI as a brainstorming companion and ‘assistant’ seem plausible, yet alongside this there have been growing concerns as to how this AI assistant will change, or make obsolete, the human researcher role. We might also re-imagine how we engage with large data sets and innovate methods of analysis that go beyond coding. Yet, due to the lack of transparency around LLM integration, inconsistency of prompt responses and constant threat of errors (hallucinations), AI is still at the moment rightly positioned as a collaborator, co-author, co-researcher, or assistant.

As we look toward the future, we wonder what it might mean for the role of human researchers to be redefined or partially replaced. What is one to make of qualitative research methods if the human researcher is no longer a primary instrument?

Consequences for technology design

Generative AI has impacted qualitative data analysis technologies in three ways: 1) through integration into the existing CAQDAS packages; 2) through the use of ChatGPT and other platforms directly; and 3) with the development of bespoke tools (i.e. AILyze, Reveal, CoLoop and QInsights). To date, traditional CAQDAS platforms are often not available due to cost or lack of resources for training. Researchers without access are likely to turn directly to Gemini, Claude and ChatGPT – tools that have not been intentionally designed for qualitative research.

Further, there is still very much a lack of transparency around the nature of the algorithms, data security levels and/or whether or not the data uploaded to AI-assisted platforms is being used for LLM training. MAXQDA, ATLAS.ti and NVivo, platforms that were initially developed by qualitative researchers for the purposes of qualitative analysis, seem to be carefully considering the consequences as they choose when and how to integrate generative AI.

Still, vigilance is required when assessing the outcomes and consequences of their use. A key part of our reflexivity should be to speak back to the developers of these new tools. The Algorithmic Justice League has documented how “AI systems can perpetuate racism, sexism, ableism, and other harmful forms of discrimination”. Dr. Joy Buoalmwini has articulated ways in which algorithmic bias results when AI systems are built on data that advantages the privileged few and causes harm to already marginalized groups. Addressing the harms to data workers, threats to the environment, data security and privacy concerns, and inherent bias would ideally be addressed by companies generating, or integrating, these models.

Consequences for human relationships

It is increasingly obvious that AI is not environmentally neutral; that is, there is clear and growing evidence that alongside the proliferation of “data centres that house AI servers” comes the production of significant “electronic waste”. The developers of large language models are amassing vast stockpiles of unethically scraped or, lately, purchased data. These are stored in data lakes and warehouses that have serious and often hidden costs, in particular, energy demands to keep the servers cool. University of Maryland Information Studies Professor Dr. Katie Shilton noted that:

Generative AI tools are trained on text and images that were created through significant human effort and creativity. After that training workers, many of them poorly paid, are contracted to flag obscene and hateful content to make these systems safe for work and for classrooms. Class activities, in contrast, prioritize students doing their own work. Benefiting from unpaid and poorly paid labor in many other people to complete class assignments is ethically fraught. If you’re using these tools to make your life easier it’s worth thinking about whose lives they made harder.

Concerningly, these environmental impacts are not equal, as some communities and regions of the world are being affected more so than others. In deciding to engage with AI, what “footprint” will our research projects leave? Is it possible to reduce our “methodological footprints” when engaging with AI?

Consequences for knowledge outcomes

As with any research technology, there is rarely one single right way to put it to use. It helps to know what the research goal is before asking generative AI for help. An AI-assisted digital research workflow could be useful to give a birds-eye, first pass of the data and to inspire particular approaches to moving forward. Or, AI could be used at the end of the research process to see if anything was missed.

While the primary discourses around generative AI and qualitative research focuses on how it will eliminate parts of the process we find boring or tedious, this may be shortsighted. As Kevin Gannon has pointed out from a pedagogical perspective, the process IS the product (Gannon, 2024):

AI tools are increasingly being used to outsource all of the process elements of meaningful learning. Take writing–struggling with ideas and creating rough drafts is part of the process of becoming a writer. Having an LLM generate a draft for you is simply shortcutting past the part of the process where actual growth–the learning—occurs.

We argue that the same is true of qualitative research. Struggling with the data, drafting possible ways of organizing the findings, and engaging in the iterative nature of making meaning through text and writing is both part of what makes a good researcher and the parts of the process often handed over to AI platforms.

Not only may we be shortcutting the process, we can’t even be sure that the AI-generated prompt responses are accurate. These models are learning based on training data that was created and curated by humans and hence subject to existing patterns of bias and discrimination. Because training data is being scraped from everywhere (without permission), there are no available metrics on representativeness or generalizability. The models aren’t transparent. As Daniel Turner, developer of Quirkos software, noted:

…one thing that these models almost certainly weren’t trained on is qualitative research, which almost never has publicly available participant data or coding frameworks that these tools could learn from. So while we can’t know for sure what data was used to train ChatGPT (which is problematic in itself), we can be fairly sure that it does not include much qualitative data, and contains inherent bias.

The consequence for knowledge outcomes is that these platforms are built to provide an answer to a prompt whether or not the underlying data is insufficient, inaccurate or biased. Responses can’t be relied on for factual accuracy; instead they are programmed to generate credible, confident responses, including realistic but hallucinated citations in persuasive and authoritative tones.

Where does this leave us? Given technologies pervade our day to day lives in known and unknown ways, we recognize opting out may no longer be an option. Yet, as qualitative inquirers, we choose to engage with caution – and to – wherever and whenever possible – opt out.

What positive and negative, intentional and unintentional consequences have you experienced in your use of generative AI for qualitative research?

AI use: This post was conceived entirely by the authors and written in Microsoft Word. The authors did invite ChatGPT to offer ideas for the title of the blog post.