Neurodiversity is generally defined as ‘the diversity of human brains and minds – the infinite variation in neurocognitive functioning within our species.’ It can be thought of as analogous to biodiversity. The term itself is neutral and is simply a descriptive term. However, the neurodiversity paradigm and the neurodiversity movement are philosophical and political perspectives that emphasise embracing neurocognitive diversity and challenging the idea that there is a ‘normal’ type of brain. Through the neurodiversity paradigm, we embrace there is variation in neurotype within our species and no neurotype is more valid than any other. Rather than being a concept of division and othering, neurodiversity is all about connection and celebrating that we are a neurodiverse species.

It’s also a relatively new term; coined in the 1990s by sociologist Judy Singer. In her words:

“For me, the key significance of the Autism Spectrum lies in its call for and anticipation of a politics of neurological diversity, or ‘neurodiversity.’ The neurologically different represent a new addition to the familiar political categories of class/gender/race and will augment the insights of the social model of disability. The rise of neurodiversity takes postmodern fragmentation one step further. Just as the postmodern era sees every once too solid belief melt into air, even our most taken-for granted assumptions: that we all more or less see, feel, touch, hear, smell, and sort information, in more or less the same way, (unless visibly disabled) – are being dissolved.”

-Disability Discourse, Mairian Corker Ed., Open University Press, February 1, 1999, p 64

From this, we see that neurodiversity as a concept comes from a socio-political standpoint rather than a scientific standpoint. It also comes from lived experience as Singer is autistic herself. She expands on her thoughts on neurodiversity in this post.

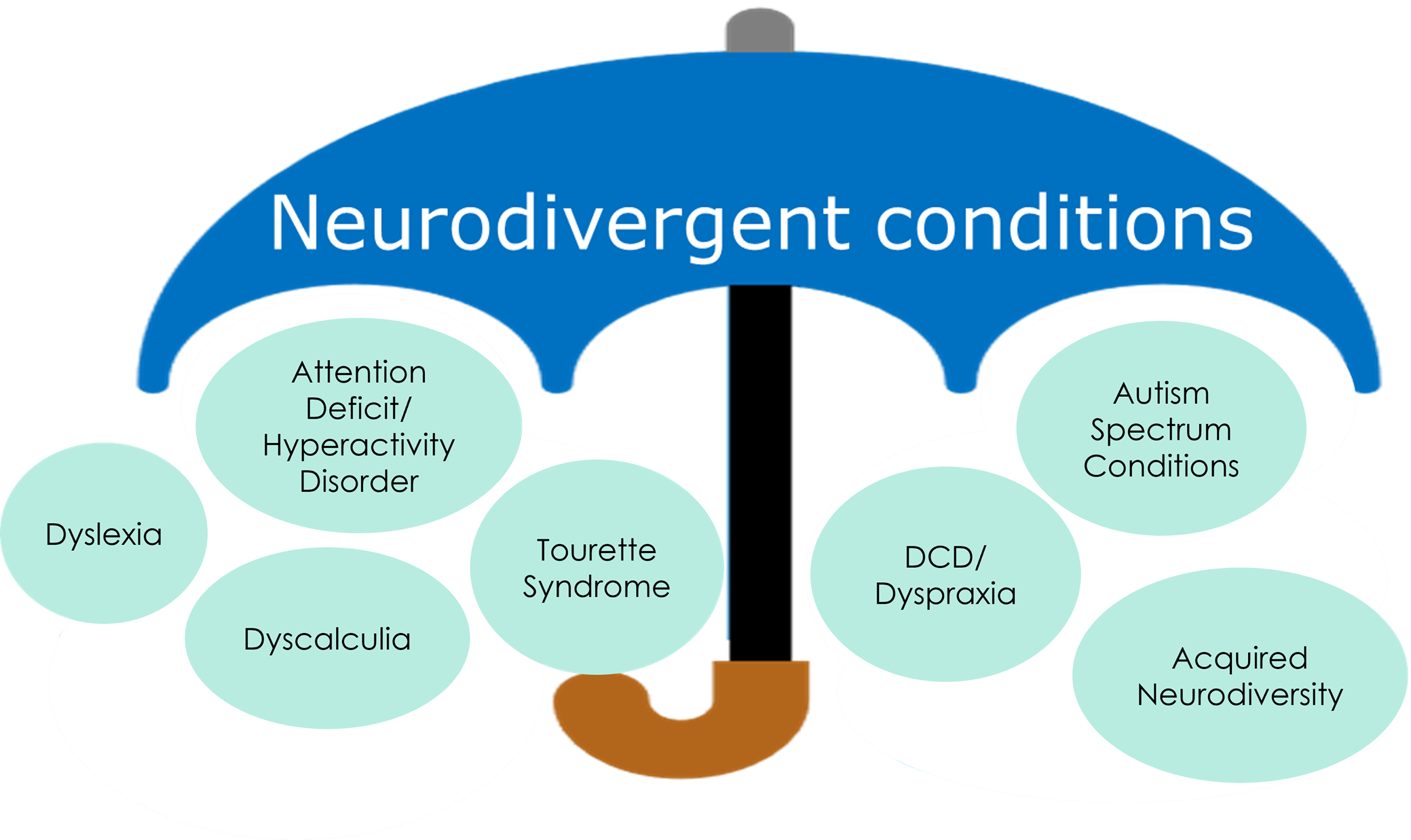

Although Singer’s thesis focused on autism, the term ‘neurodiversity’ is now used more broadly as an umbrella term for people with neurodevelopmental differences. These include ADHD, autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, and Tourette’s syndrome (note that this is in no way a comprehensive list). These are often referred to as ‘neurodivergent conditions’ and one could describe people in this group as ‘NeuroMinorities’.

Because neurodiversity is a relatively new concept, its meaning is still being formed within our social consciousness. Many people point out the differences between the term neurodiversity itself, the neurodiversity paradigm, and the neurodiversity movement. This article defines some of these different terms but it should be noted that people sometimes use different definitions. For example, some people do refer to themselves as ‘neurodiverse’ even though linguistically it might make more sense to stick to just ‘neurodivergent’. While I try to stay consistent with how I use such terms, it’s important to acknowledge that as we are still forming the language to talk about these aspects of our species, things have and will change over time.

One core aspect of the neurodivergent experience that is often cited is that of a ‘spiky profile’. That is, in neurodivergent people we see a profile of skills and perceptions that is inconsistent, whereas neurotypical people tend to have a more even neurocognitive profile. For example, a neurodivergent person may have exceptional artistic and musical skills but lacks the ability to plan ahead and struggles with basic self-care. To find out more about this concept, this page from ‘Genius Within’ is worth reading. Neurodivergent people are wired differently and experience the world differently which means that sometimes we need support and adjustments to function in everyday society.

Want to read more about neurodiversity?

Check out our Neurodiversity Network Resource Padlet for lots of links to resources and the Neurodiversity at Surrey blog to hear what the neurodivergent community at Surrey has to say.

Celebrating neurodiversity at Surrey

Inspired by other equality, diversity, and inclusion initiatives at the university—such as the rainbow network– we recently established neurodiversity networks for staff and students. You can join a network as a member or as an ally to show your support for the neurodivergent community. The sign-up form can be found here and feel free to get in touch via email at studentNDnetwork@surrey.ac.uk or staffNDnetwork@surrey.ac.uk

.