I moved to the UK from Zambia when I was 13. My mothers father was white British and moved to Zambia during the colonial rule of the country. Unlike many other white men at the time, my grandfather wasn’t wealthy at all. He was a young tradesman from Stoke-on-Trent who moved to Zambia as there was a need for skilled labourers to build bridges, decorate buildings and other manual labour. During his time there, he met and fell in love with my grandmother, a black Zambian woman who he went on to have 10 children with. At the time this was illegal and when the authorities found out my grandfather was with a black woman he was cut off from all funding and employment. This meant he was unable to return to the UK and died in Zambia in the 80’s. He wasn’t just cut off financially, but from family too. He had siblings that never heard from him, never knew who he married or how many children he had, never knew when he died or whether he was happy. And yet still, he sacrificed what would have been a life of financial, social and political security as a Brit to start a family with a woman who his own people considered to be below him. Whilst my grandfather’s race certainly had its privileges, I highlight this backdrop as way of making the less known stories of white people who chose to lose that privilege for love, justice, equality and fairness.

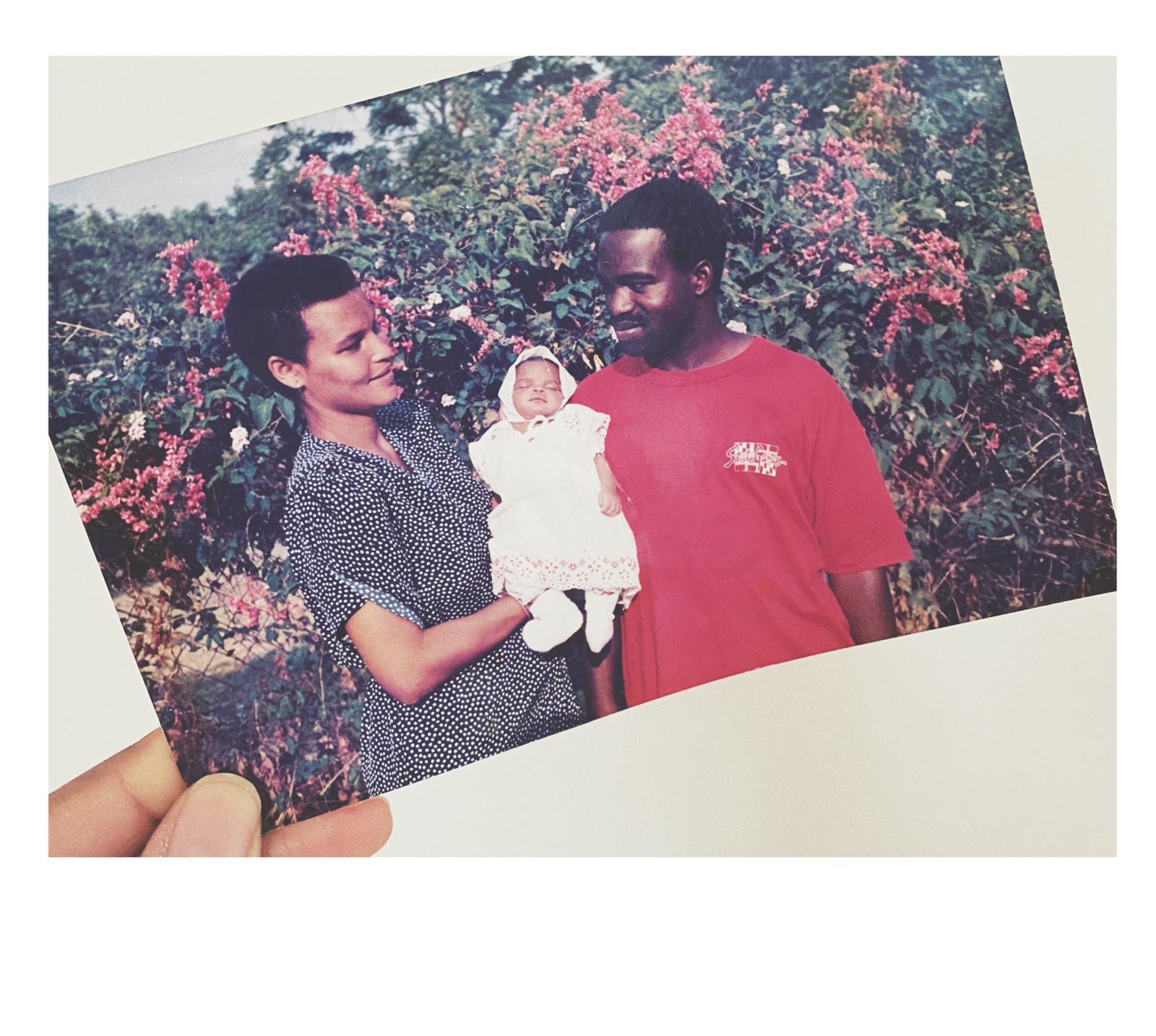

My mother was born in the year Zambia gained independence from British rule. As a mixed race woman, she grew up with a varied experience of privilege and discrimination, receiving preferential treatment for her evident whiteness as well as being victimised for being related to ‘the oppressor’. My mother has always been a stunning African woman, but in Zambia this was often only credited to her based on her European features; her lighter complexion; a warm cappuccino tone, her hazel eyes that have a wonderful range of expression in them, and her angular nose of particular interest to many. My father often jokes about winning her over because mixed race people were at the time (and in many ways still are) seen as prizes to be won – a remnant of the imperial mindset that places higher value on whiteness.

I experienced some of this myself growing up in Zambia – my complexion and features visibly indicate the mixture in my somewhat heritage. I was often singled out and othered in ways that were mostly beneficial for me. I now know that to mean privilege.

A really significant part of migrating to the UK has been redefining our familial racial identity. Here – my cappuccino toned mother is still a proud African woman but her experiences are shaped by her being perceived as undeniably black instead of her whiteness. I am deeply aware of the fact that anti-blackness is embedded in all of us and it is our responsibility to engage in uprooting these beliefs and values in ourselves then in our communities. The black lives matter movement has been for me a realisation of some of the parts of my culture, and being as a black African woman that I have suppressed and silenced in order to fit in and thrive in the UK. I’m saddened that my accent doesn’t reflect my Zambian upbringing much, I’m saddened that I’d probably feel out of place if I decided to wear my African print headscarf to work, I’m saddened that some people still call Zambia ‘Northern Rhodesia’ (don’t do that!).

But I also have hope. Hope that as I learn and unlearn the deep intricacies of my life and lineage, that my black children will be able to do that quicker and better.