By Kaya Holder

© K. Holder,2021

Would you change your name if it was more lucrative or opportunistic to do so? For instance, imagine if all UCAS applications to Surrey were nameless and therefore solely based an academic skill and nothing else. What would be the impact on intake, the student body and the wider Surrey community I wonder? This idea was proposed in 2016 by David Cameron, as a potential way to remove discriminatory, subconscious bias and blockers for POC in HE by way of a ‘name-blind’ approach but was rejected unanimously by the HE and Oxbridge communities. This article will explore some reasons how names and bias affect job opportunities, educational achievements and daily micro aggressions.

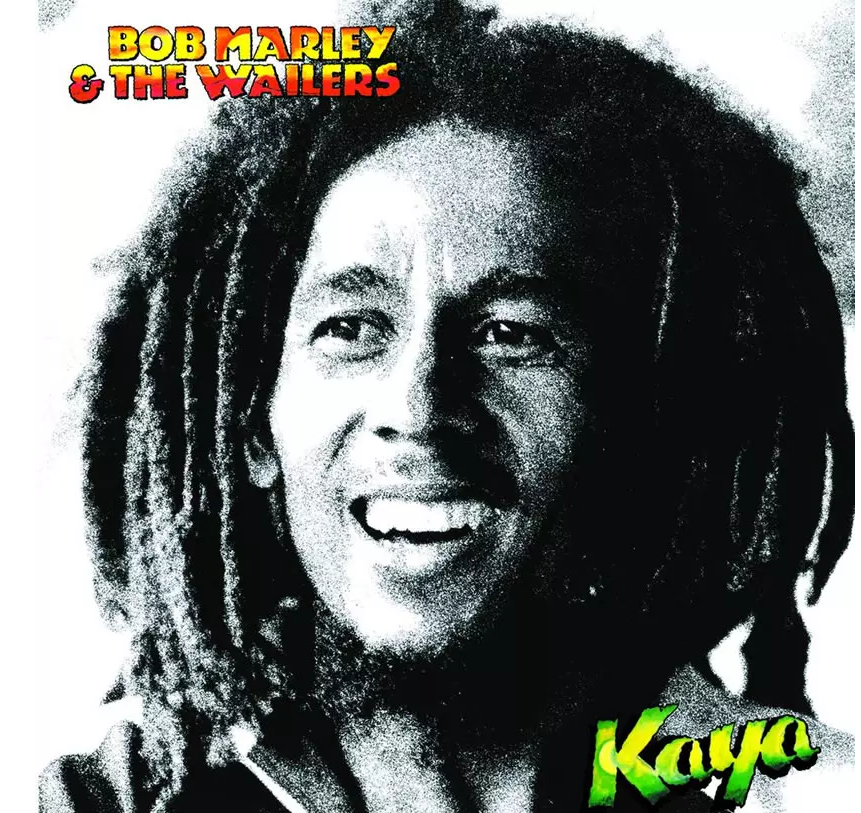

For many POCs, your name carries a plethora of predetermined assumptions. It can be a source of conversation, a cultural reference, link to your diaspora or simply a proud family tradition. My name, Kaya, can often be attributed to all. Most notably, my name became a conversation starter when I lived in Japan for several years, because as luck would have it, Kaya is also a Japanese word, so can easily translatable to the Japanese hiragana script, which generally foreign words can’t. For the first time in my life everybody I encountered could read and pronounce my name perfectly!! “Kaya”, かや, 茅 is a type of thatch/grass as well as an area in Tokyo called ‘Kayabacho’ so it became a fun way to introduce myself. Culturally I would explain that my name represents my heritage and that I was named after a Bob Marley album and song (see image 1). Growing up my dad and my paternal family were huge reggae fans, so this correlates unswervingly with my West Indian heritage. Furthermore, my surname ‘Holder’ is the equivalent of ‘Smith’ in Barbados, so it’s usual for me to meet people with my surname or see a street with the name on whenever I visit.

Before going to Japan I had only really considered my name as part of my individuality, however in a culture where your surname becomes your work prefix, as well as your house name, it dawned on me the predominance on first and not second names is unique to the West (note: ask me about middle names and almost missing a flight to Hawaii in person). If people refer to me as Holder Sensei, I would often not respond to their dismay due to the British preference to envelop our first names predominantly. Therefore, being the odd one out anyway, I would be known as ‘Kaya Sensei’ which was not only of familiarity but demonstrated acceptance of my individuality.

Back to the question in hand, have I suffered negatively as an impact of having a non-English name being born in England? Unfortunately, the answer would be yes. According to the authors of ‘Slay In Your Lane’, there are multiple instances where your name can block opportunities. For one, they refer to a Guardian article whereas a job applicant listed their job application under an English name with the exact same work experience history and obtained an interview. They also applied for the same role with their authentic name yet even with the same experience failed to get shortlisted. 1

There are many instances upon arriving in England, whereas non-UK citizens have adapted their names to fit the status quo, but is this just cultural assimilation or a step too far? In many ways microaggressions and mispronunciations are avoided entirely once you remove the cause, but is this acceptable in 2021 as an approach? Personally, I think removing names from job applications, LinkedIn profiles, UCAS etc eliminates this obstacle, without the sacrifice of having to denounce your name. Ultimately, I try to positively approach meetings with new people and if asked, am happy to explain the meaning, context and cultural connotation of my name. I’ve also added the pronunciation to my email signature to encourage and allow others the opportunity to know without having ‘that’ discussion should they find it awkward. I don’t consider being called anything else a microaggression, but it is disappointing that these two syllables aren’t important enough for a colleague or acquaintance to remember. I would wholeheartedly welcome the removal of names in the job/university of application process, to remove any stigma or managerial concern over mispronunciations or awkward scenarios, as well as level the playing field.

Sources

Adegoke, Yomi; Uviebinené, Elizabeth. ‘Slay In Your Lane’ (2018). HarperCollins.

Anon. ‘I applied for the same job using an English name and got the interview.’ (24 March 2016). Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/media-network/2016/mar/24/british-journalism-female-ethnic-minorities-reporters-editors