Winner of the 2018 CES World Environment Day blog competition:

Author: Ceri Fenwick

Open up the arguments, and things are more complex than they first seem.

When I first heard about the right to repair movement, which is currently stemming from the US, I thought it could only be a good thing for the environment. Give consumers the power to make their products live longer, by regulating companies into making schematics, spare parts, and firmware and so on available to all who ask. Since starting my doctorate, based in the technology industry, I have started to understand the practicalities and challenges of implementing sustainable development concepts in organisations. I have come to question more and more why this repair movement may not be the sustainable solution it first seems.

Firstly, there are some elements of designing for repair that may clash with designing for a longer product lifetime (i.e. durability). A good example is waterproofing, which tends to improve a product’s lifetime but does make disassembly for repair more difficult. This is especially true for mobile phones, as they are usually carried everywhere by the user, thus increasing risk of being exposed to water. Once a phone is taken apart; it would be very difficult to waterproof it again. So how do we decide between trade-offs in designing for durability or designing for repair? It will depend on many factors, such as the product itself, how the product is used by the consumer, expected lifespan and so on. I would argue that generally speaking products should be as durable as possible, in order to reduce the need of repairs in the first place.

However, even that argument may be too simplistic when you consider the environmental impacts of electronics in their use phase, which is mostly how much energy is consumed. As products are released that are more energy efficient than previous versions, companies often consider when it is worth switching a product sent in for repair for a newer or upgraded one. This can be better for the environment by reducing the consumer’s energy use. There are many factors to consider when trying to ‘eco-design’ a product and without information on what happens throughout it whole lifecycle, it can be easy to make assumptions that may not be true in reality. To introduce Ecodesign legislation that prioritises reparability over all else would mean manufacturers may not be able to consider the other product specific attributes to make the best ‘eco’ decision at the product design stage.

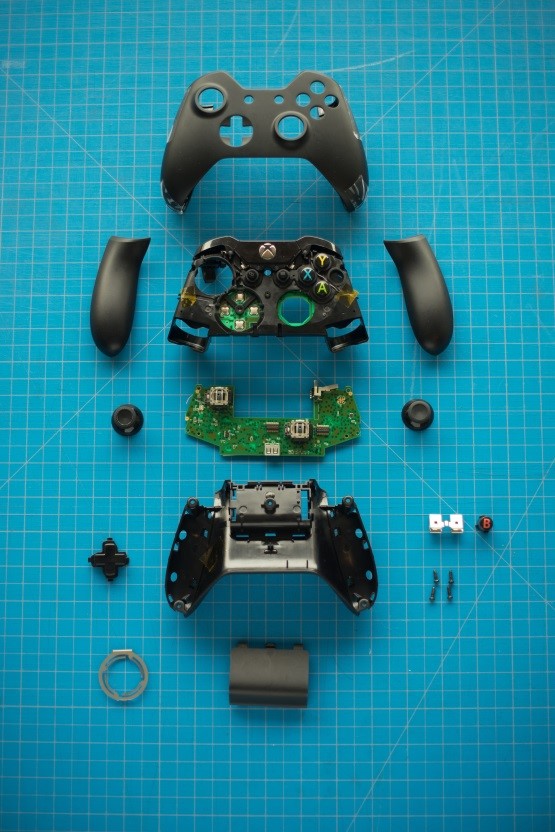

The Right to Repair movement also doesn’t seem to be concerned about the risk of increasing waste through poor repair practices. Just because products can be disassembled and schematics can be provided, doesn’t mean a consumer has the skill to fix it. Complex electrical products require specialised repair, in order to maintain the quality of the product, as well as making sure consumers won’t accidentally electrocute themselves! In these cases, it would be best to have skilled personnel carry out the repair in order to make sure it is successful, reducing e-waste as well as addressing quality and safety concerns.

Logistically and environmentally, using regulations to make it compulsory for manufacturers to make spare parts widely available is another area where the right to repair arguments have not been fully developed. Availability of spare parts is not a feature that can be designed into product durability or reparability, as availability in practice is influenced by many things, including those outside of a manufacturer’s control. Distributing spare parts to individuals rather than central warehouses would dramatically increase environmental impacts associated with transportation. In addition, making availability of spare parts mandatory for a certain number of years may actually lead to overstocking; which would have a negative environmental impact, through increased and unnecessary manufacture.

As stated above, electronic products are complex and often there are a variety of ways to facilitate their repair. In fact, one product may have options for repair or upgrade by the user, as well as a manufacturer-led repair process; the two are not mutually exclusive. Any legislation will, therefore, have to consider the variety of repair options available for any given product groups and not just consumer-led repair.

The manufacturer may spend time, money and resources on designing products to last longer, increase reparability, upgradeability and recyclability but it is still completely up to the consumer to use these features. How many people will choose a new product instead, for its ‘new’ look, improved specs and so on? How many will dispose of their products responsibly? Right to Repair seeks to give consumers back control of their products, but as consumers do not currently always choose the more environmentally friendly option, will this be any different? Ultimately future Ecodesign and waste legislation for consumer goods cannot focus on one area of product design and should consider the all of the issues discussed in this blog (as well the issues not discussed!), in order to reduce the environmental impact across a product’s entire life cycle and therefore to become more sustainable.

What is “Right to Repair”?

Right to repair legislation, also known as the fair repair act, is being introduced and debated throughout the US; aiming to give individuals the ability to repair their own products. Originally stemming from farmer’s efforts to repair their own tractors without access to proprietary diagnostic software, this movement has now caught the eye, and criticism, of big tech firms who argue that not all should be allowed to carry out repairs.

Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this blog lies entirely with the author.

Images used are in the public domain, sourced from https://unsplash.com/