‘Great Beasts Isolated on Mountains’ (see citations in the text). Image: Crocodile from the Rochester Bestiary. Wikimedia Commons

What did it mean to read and write as a medieval woman? This is of course one of the big questions that the Women’s Literary Culture network is investigating: scholarly work on the writings of Margery Kempe and the Paston women, discussed in other blogs on this site, has highlighted issues of agency and style to help answer this. Yet I think it is a question with an urgent contemporary aspect too: what does it mean to read and write about medieval women as a female medievalist in the 21st century? What follows is a short, personal, and to my surprise a statistically-focused reflection on this question from my perspective as just such a medievalist. It makes no claim to being definitive, but might give some food for thought.

Recently I’ve been researching a chapter on the antique texts of Alexander the Great. As a medievalist with a shaky grasp of classical literature, it was a fascinating learning curve, but what struck me the most was the maleness of the scholars. Only 15% (13 out of 86) of the secondary works I read were by women. This shouldn’t be surprising, perhaps, given the historical position of the classics in the UK school system as the mark of a prestigious (and mostly male) education, but what struck me more forcibly than the gender of the critics was the genre of their criticism. Mostly dating from the 1960s onwards, the majority of the research was focused on identifying sources and judging historical accuracy. In other words, it was mainly empirical and ‘scientific’, interested in facts and figures. This approach is a historically contingent trend found more widely, but what is more surprising is that it seems to have continued to dominate in Alexander studies after newer approaches had become the norm in other areas of classics. A memorable review of contemporary Alexander research highlighting this was published by James Davidson in the LRB in 2001: https://www.lrb.co.uk/v23/n21/james-davidson/bonkers-about-boys

‘In Alexanderland scholarship remains largely untouched by the influences which have transformed history and classics since 1945. Some great beasts, having wandered in, can still be found here decades later, well beyond reach of the forces of evolution. Secluded behind the high, impassable peaks of prosopography, military history and, above all, Quellenforschung, Alexander historians do what Alexander historians have done for more than a hundred years.’

Davidson describes eloquently what he sees as a problem for Alexander scholarship. What I find fascinating, and disturbing, is the language and imagery he uses here: surely deliberately, he talks of ‘great beasts’ (dinosaurs?) isolated on mountains, simultaneously invoking aggressiveness and isolation. He is describing predominantly male critics in terms that construct a sense of traditional maleness: physicality, self-sufficiency, a position at the top of the food chain and of the geographical world. Although I don’t think Davidson meant to link gender to the critical tendencies this imagery suggests, this is the effect: ‘this is the kind of research men do’. One could argue, a bit crudely, that gender, approach and critical genre correlate: being a man results in researching like a man, and ‘researching like a man’ means a focus on source study and empirical evidence. Alexanderland is for men and masculinity.

This is a bit of an exaggeration. But it has important implications, I think, for medievalists. Are there areas of medieval studies that experience the same apparent correlation of gender and critical approach? What would this mean for the discipline as a whole? My own experience to date has felt gendered in two fields in particular, namely medieval Latin studies and romance. I started to investigate whether my instinct was an accurate reflection of the fields by spending an evening trawling databases.

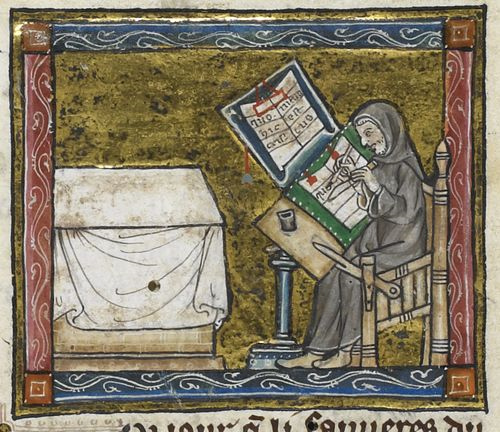

Detail of a miniature of a hermit at work on a manuscript, from the Estoire del Saint Graal, France (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315 – 1325, Royal MS 14 E III, f. 6v. British Library

For medieval Latin, the results were apparently stark. Given the vast number of potential hits, I searched for articles on the twelfth-century Latin epic Alexandreis, a major school text that survives in over 200 MSS, to delimit the search area and also to test my ideas about Davidson’s imagery on similar ground. I found 54 articles listed on a well-used medieval database (not all completely focused on the poem, in fairness), of which only 14, or 26%, were written by individuals with names generally applied to women (with no allowance made for multiple entries by the same scholars, which would probably bring the percentage down even further). So there appears to be a marked gender imbalance, at least in studies of this Alexander text.

The next question I asked was whether this imbalance might be related to the kind of critical work undertaken on the poem. Looking at the 54 articles, I found only 11 that seemed to adopt more ‘literary’ and thematic approaches. This statistic seems to support Davidson’s hypothesis about classical Alexander literature in this medieval context: it is empirical and factual evidence, like manuscript studies, editing, and source study, which has caught scholars’ attention. What is especially interesting is that of these 11 more ‘literary’ approaches, 46% (5), are by women: although this is a small sample from which to extrapolate, there appears to be a strong correlation between gender and approach. In medieval Latin Alexander studies, then, women apparently research differently from men, focusing less on manuscript studies, editing, and source study and more strongly on thematic and ‘literary’ approaches. Going back to Davidson’s dinosaurs, we could crudely assume that female scholars are less interested in questions of sources and empirical historicity than in more thematic study: women ‘research like women’. This is a big claim to make from a very small sample, and I’m no statistician: in addition, individual women have made vital contributions to medieval Latin manuscript studies and editing (Jill Mann’s Ysengrimus edition, for example). However, I think what is clear is that Medieval Latin (as represented here) is, firstly, a discipline unequal in terms of gender balance, and, secondly, one that does not display the variety of scholarly approaches that can be found in other areas of medieval studies. It’s evidently not just Alexander studies that can be found, roaring, holed up in mountain fastnesses.

Perhaps this ‘maleness’ in medieval Latin can be explained in part by school-level education. From anecdotal evidence, it seems that men are more likely to learn Latin before university, and therefore to have greater access to degrees focusing upon the language, than women: my younger sister, for example, was the only woman reading classics in her year at her Oxford college (although she thought the overall balance across all the colleges was a reasonable 60/40 male/female), and she initially felt disadvantaged by her male peers’ greater language skills gained at their schools. Yet I don’t think there is any similar explanation for the apparently equally gendered nature of the other field in which I work, medieval romance.

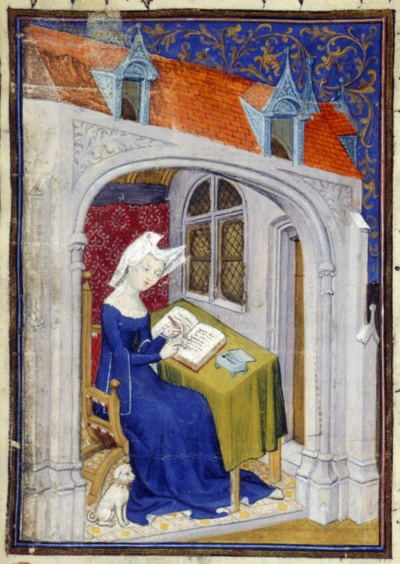

Detail of a miniature of Christine de Pizan in her study at the beginning of the ‘Cent balades’, Harley MS 4431, f. 4r. British Library

In complete contrast to medieval Latin, romance studies is dominated by female medievalists: certainly many of the field-defining scholars working on romance over the last twenty years are female. Helen Cooper, for example, has not only played a significant role in constructing romance studies’ parameters, but has been the scholarly catalyst for many other important scholars who began academic life as her doctoral students: as the first female fellow at University College, Oxford, and latterly as the Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge, her influence has been and remains immense. Statistics also seem to support this sense of a field driven by women: at a recent fascinating conference on romance, 71% of the listed speakers were female.

However, there is no pre-existing reason that I know of, unlike Latin education, for this female dominance in romance studies. It may be in part because of the importance of feminist and gender studies in the field, for which it has of course been a fertile area, particularly for research into women’s literary culture. Such research is far from being exclusively the preserve of women, but another database trawl with ‘romance’ and ‘gender’ as search terms brings up 100 hits, with 26 by individuals with names traditionally given to men. (This is a very neat statistical reversal, since exactly the same percentage – 26% – was attributed to female names for articles on the medieval Latin Alexandreis above.) It would seem that one reason for women’s engagement with romance studies is because of this theoretical approach, which seems to resonate with female scholars in particular. So again there seems to be a certain relationship between critical approach and scholars’ gender.

Does this relationship mean that women ‘research like women’ in romance studies more widely, however, as is potentially the case for medieval Latin? Interestingly, moving away from gender studies makes the case less clear-cut. A database search for ‘romance’, refined by ‘manuscripts and palaeography’ (the nearest option to ‘source study’ available) makes this clear: it gives an almost exactly 50% gender split by name for the first 100 entries. (These entries only cover the last 10 years or so: it would be interesting to see if the gender balance is different in past decades.) So this example contradicts the apparent situation in medieval Latin studies, since both men and women are ‘researching like men’. Does this mean that the apparent correlation between scholar and subject, between academic and approach, is only demonstrable from a very sweeping perspective, and breaks down on closer scrutiny? Or is it the case that different fields attract certain kinds of research (and researchers) for reasons that are not primarily to do with gender? I don’t know: a lot more research is needed. In any case, these delvings into romance studies’ statistics seem to show less of a correlation between gender and genre of criticism than is the case for medieval Latin.

These brief investigations have made me realise just how complex a business identifying connections between medieval studies and their medievalists is. Certainly I would not claim any essentialist relationship between field, gender and mode of research, either from a personal perspective or an analytical one: as I said above, I’m no statistician, and I can’t get away from the suspicion inherent in ‘lies, damned lies, and statistics’. However, if we return to the larger question of what gendered fields and (potentially) approaches might say about medieval studies more widely, I wonder whether lack of gender balance might be one sign of other biases with an impact on scholarship: are we creating silos and echo chambers in which we simply talk to others like ourselves, and therefore aren’t challenged to look out beyond the horizon? Recent conversations about lack of ethnic and racial diversity in the academy come to mind here as a parallel. From this perspective, gender and critical genre are only one aspect of a larger question about who we are collectively, and how we relate to, and reflect, wider society in the 21st century: whether we choose to stand bellowing on distant peaks or to reject seclusion and evolve into different, more expansive individuals and institutions.

Whatever our personal perspectives on that question, I want to end by returning to the issue of what it means to write as a medievalist, of any gender, in the 21st century. Beyond all the database trawling and statistical wrangling, if we accept that as medievalists we reflect our own experiences and views in our choice of subject and our approach, then there is a relationship of fundamental importance between what we write and who we are, between our textual and extra-textual selves. In researching women’s literary culture and the medieval canon, then, we are not just undertaking ground-breaking research: all of us, whatever our gender, approach, or background, are writing ourselves, prehistoric or otherwise.

Dr Venetia Bridges