In the International Women’s Day blog we posted yesterday we looked at some of the key events in the life of artist Eilean Pearcey. In our second blog Art Collection Audit Officer David Wootton looks at Eilean’s highly significant work in the depiction of Indian dance.

Eilean Pearcey and her images of Indian Dance

As an artist, Eilean Pearcey is synonymous with images of dancing and dancers. She was first inspired to focus on these in the late 1920s on seeing a performance by the great Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, and her company during a tour of Australia. This led to her meeting and drawing Pavlova, and then to her receiving introductions to other major figures in the world of dance. Following her move to London in 1931, she became a familiar presence in many a theatre, sketching performers from the stalls or the wings. Increasingly, and especially from the 1960s, such sketches became the basis of drawings that illustrated the promotional material of dance companies and other publications, including magazine articles written by Eilean herself.

As demonstrated by the wealth of drawings in the Archives of the University of Surrey, Eilean engaged with both a wide variety of dance forms and the many companies that presented them, and she adapted her medium and approach to best capture each subject. Not only did these subjects encompass the classical art of the Kirov Ballet and London Festival Ballet (now English National Ballet) and the modern dance of the Martha Graham Company and London Contemporary Dance Theatre. They also ranged across many non-western cultures and included such genres as Kabuki and mime, which elided dance with other theatrical traditions. Indeed, as her friend and executor, Sir John Drummond, recalled in his obituary of her, ‘her greatest enthusiasm was for Indian dance’ (Independent, 19 February 1999).

Eilean’s enthusiasm for Indian dance was sparked when she was introduced by Anna Pavlova to Uday Shankar. Inspired by her visit to India in 1922, Pavlova had commissioned Shankar, who was then a young art student in London, to create two Indian themed ballets for her. As a result, he choreographed and designed A Hindu Wedding and Krishna and Radha, and danced in them at the Royal Opera House in October 1923. Eight years later, in 1931, he settled in Paris and established the first Indian dance company in Europe. And, in that same year, Eilean and her husband, Allan Ramsay Moon, moved from Australia to England. Her introduction to Shankar probably came soon after, and she became a devotee of his company’s performances, making drawings of them and promoting them in the press. In one article, aimed at an Australian readership, she wrote that ‘Uday Shan-Kar is a great dancer … The poetry and spirit of the dance is never crushed beneath the weight of the technique’ (Herald, 14 January 1938).

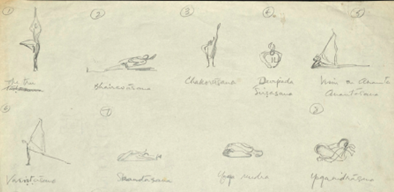

Through the decades, Eilean’s knowledge and understanding of Indian dance, music and general culture broadened and deepened. As John Drummond explained in his obituary, she benefitted from ‘the important work of the Asian Music Circle’, founded in London in 1946 by Ayana Angadi and his English wife, the painter, Patricia Fell-Clarke. Despite its name, the AMC encouraged a wide range of communications and collaborations between British and Indian creative figures, and brought many performers to the capital, whom Eilean then befriended. It even introduced yoga into Britain by hosting the classes of the teacher and author, B K S Iyengar. Eilean came under his influence, and ‘from being an enthusiastic student … in late middle age, [she] became an outstanding teacher’. Furthermore, she illustrated his handbooks on yoga with her crisp, clear line drawings, as she did The Music of India (1976), written by her friends, Jamila and Reginald Massey. Not content with absorbing these influences in her adoptive home, she also travelled to India, and subsequently gave a talk on the temples of Bhubaneswar on BBC radio’s magazine programme, Woman’s Hour.

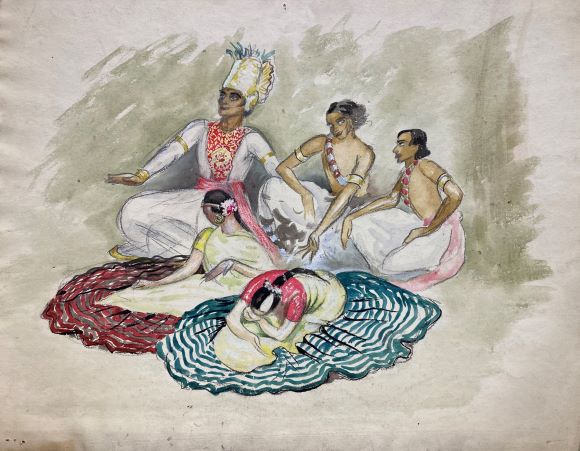

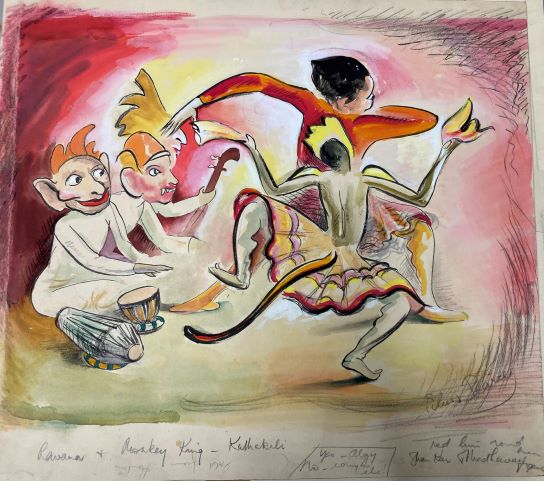

In the mid-1980s, Eilean donated to the University of Surrey a group of drawings and paintings of Uday Shankar and his company in performance. They relate to some items in the much larger, more comprehensive bequest that was accepted by the University following Eilean’s death in 1999. Together, they well characterise the artist’s approach to depicting Indian dance, as they include studies and finished watercolours of the same compositions. The current blog highlights two compositions that date from the 1930s: Ravana and the Monkey King and Siva and Gajasura.

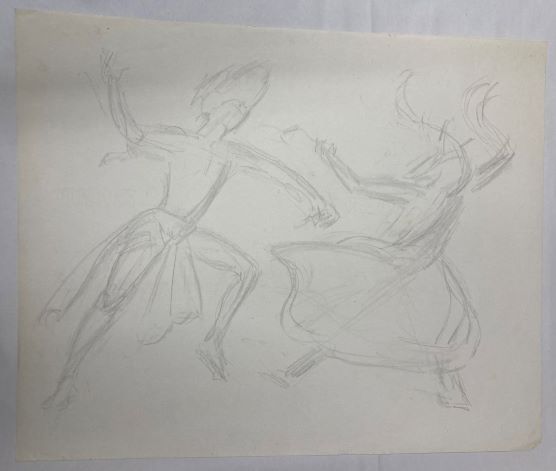

The dance of Ravana and the Monkey King was based on the fifth book of the Hindu epic, the Rāmāyana, and enacted the successful attempt of the monkey king, Hanuman, to rescue Sita from the demon king, Ravana. Shankar’s version drew on the Kathakali dance form of southern India, which incorporates athletic movements and employs brightly coloured costumes. Both are caught brilliantly by Eilean in her vibrant and dynamic painting, which she arrived at via a fluent pencil sketch (both EP Portfolio 13) and a strong outline drawing in ink (Art Collection). Accompanied by musicians wearing large false heads, Hanuman seems to taunt Ravana in echoing his demonstrative gestures and wide steps.

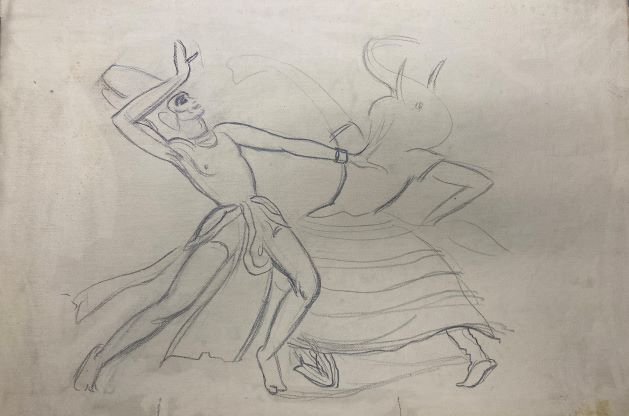

Eilean’s other sequence, showing the dance of Siva and Gajasura, is, if anything, even more dramatic. Based on an episode of the Hindu text, the Kurma Purana, it shows the god, Siva (or Shiva), battling with the demon, Gajasura, who has taken the form of an elephant in order to terrorise a community. The beautifully balanced composition of the culminating painting (in the Art Collection) indicate a well-matched struggle, though the position of Siva, the expression on his face and the gesture of his hand all suggest that he is likely to be victorious. And while the vivid colour was introduced late in the work’s development, its electric sense of movement was sustained from the immediate early sketch and throughout (EP Portfolio 15).

Siva was almost certainly danced by Uday Shankar and Eilean’s depiction may be considered a portrait of him. The witness to so many of his performances, she can describe him better than almost anyone else, in word as well as image, and under one drawing of him as Siva, which accompanied her article in the Herald, sits the phrase, ‘all is gracious and flowing’. It sums up the best of her art as well as his.