Written by Nikolai Kutsch with Professor Amelia Hadfield. Nikolai is an undergraduate international exchange student from North Carolina State University, North Carolina, US, who is studying Politics this year at the University of Surrey. He is joined in this blog by Professor Amelia Hadfield, Head of Politics and International Relations at the University of Surrey.

Following the political developments of America is a favourite, indeed long-established pastime. King George III famously expressed his astonishment at George Washington’s decision to resign the Presidency after two terms, saying this voluntary relinquishment of power rendered Washington – his wartime adversary – “the greatest man in the world”.

In recent times, British political leaders remain more than willing to wade into the American political fray, particularly an election. It isn’t always plain sailing, however.

From “sociopath” to “common cause” – Britain’s diplomatic approach to the Special Relationship

In 2018, current Foreign Secretary David Lammy, then a backbench Labour MP, lambasted the former president in a TIME article ahead of his first official visit to the UK. Then, Lammy labelled Trump a “woman-hating, neo-Nazi-sympathising sociopath” and “profound threat to the international order”, accusing him of “racist attacks on the U.K.” and citing his “sympathy for white supremacists” during time in office.

As British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson directed criticism at Trump following the January 6th insurrection in 2021, arguing that Trump had “encouraged people to storm the Capitol” and worse, had “cast doubt on the outcome of a free and fair election”. By 2024 however, Johnson had shifted his stance considerably, praising Trump for facilitating a “peaceful transfer of democratic power” and denying that the former president had ever intended to “overthrow” the Constitution.

In the final weeks running up to the November US election, little has changed. Democratic Vice Presidential nominee Tim Walz’s plea to “mind your own damn business” made headlines at the Democratic National Convention. The Minnesota governor was in this case prescribing a hands-off approach to women’s reproductive freedoms, but the phrase is equally helpful in summing up the rule of thumb for British – and indeed all international opinions – lobbed towards America in during election season. Indeed, that would be the preferred approach for US politicians during and after the election: minimal intervention from other governments alongside a willingness – however pragmatic – to work with whoever

resides in the White House. The irony is that while being in opposition represents something of a licence to punch candidly, being in government inevitably requires individuals to replace boxing gloves with softer versions. Six years later, and now heading the Foreign Office, Lammy has demonstrated reluctance to deem Trump a racist. Instead, he emphasises the importance of finding “common cause” and ways to “work together” with whichever U.S. leader succeeds the Biden administration. Lammy isn’t alone in his hushed noninterference – Keir Starmer’s dedication to preserving the “special relationship” regardless of the election results extends across his government.

Yet not all prominent Labour voices are joining Starmer’s chorus of non-partisanship. London Mayor Sadiq Khan, known for trading barbs with the former president via tweets during his presidency, has remained a vocal critic. While urging Americans to vote for Democratic nominee Vice President Kamala Harris, Khan described U.S. politics as a “metronome” with the potential to set the tone across the world for the political culture of the years ahead.

This remark may also explain why many Labour activists, unburdened by the politeness of government, feel empowered to voice their preference for Harris. Yet in picking a side, they are entering the fray, and run the risk of getting caught in the crosshairs of current and former US politicians, who may not appreciate their presence.

Indeed, two weeks before decision day, Trump’s legal team accused the Labour Party of “foreign interference” in a letter to the Federal Election Commission. This followed a LinkedIn post by Labour operative Sofia Patel, in which she announced “10 spots available” for party activists interested in travelling to North Carolina to campaign for Democrats.

Though the legal reasoning is questionable (Labour is not paying activists’ travel expenses and “spots” refers to accommodation at the homes of Democratic volunteers), Starmer’s quick dismissal of Labour involvement indicates his determination to continue to project neutrality. With Trump having vowed retribution against his adversaries as a top priority in a second term, it may come as no surprise that Labour have an interest in placating the volatile personality who might be inaugurated as president in less than three months.

Britons keep a close eye on the US elections – and desire certain outcomes.

Away from the world stage, the British public is increasingly tuning in to US news, with clear opinions: both on which candidate they prefer, and which they see as most likely to win. This campaign however, is unlike any other. It represents one of the shortest head-to-heads in U.S. history after presumptive Democratic nominee President Joe Biden dropped his re-election effort following a stumbling debate in July.

Possibly because of the US election’s truncated timeline, Britons’ views have shifted throughout its duration. Ipsos polling in July 2024 – the month Vice President Kamala Harris entered the race – found 50 percent of respondents favoured a Harris victory, with only 21 percent preferring her opponent. Support for Harris was especially high at 72 percent among respondents who voted for Labour in the 2024 UK general election and lower among Conservative voters at 38 percent.

This suggests that for many Britons, ideological divides transferred and translated wholly or in part from the ecosystem of British politics colour their view of American affairs accordingly. The historically friendly relations between Republicans and Conservatives as well as between Democrats and Labour is certainly well established. But how these preferences actually translate into forms of political partisanship based on expectations of a preferred candidate actually winning is a separate matter. Indeed, partisanship seems less important in estimating candidates’ chances. That same poll showed 49 percent of British respondents expected Trump to win the race while only 22 percent saw a clear path to victory for Harris.

By October 2024, the ground had shifted dramatically not only in American polls, but in a further survey of Britons, this time by YouGov. Here, Harris had gained significant traction as 64 percent of British respondents preferred her and only 18 percent – boosted by the 54 of the respondents aligned with Reform UK – backed Trump. Favourability for Harris had leapt to 57 percent among Conservatives, and to well over 80 percent for Labour and Liberal Democrat supporters.

While the vast majority of these surveys’ UK-based respondents will not have the chance to cast a ballot in the US election, such polling is purely hypothetical in its consequences. Hundreds of thousands of British citizens reside in the United States, and many of those will have acquired US citizenship, and with it, the right to vote. Equally, according to Politico some of these have expressed their approval for Trump particularly on the economy, these British Americans could be influenced in part by conversations with friends and family back in the UK imploring them to vote for Harris.

The United Kingdom – a swing state hidden in plain sight?

Even thousands of miles away from American shores, the US election is playing out on British soil, as groups like Democrats Abroad and Republicans Overseas urge Americans living in the UK to make use of their federally-protected right to cast their ballot from abroad.

According to Statista, as of 2021, nearly 166,000 Americans were resident in the UK. This figure represents tens of thousands of votes that could help shift, or even flip key swing states, particularly those like Georgia and Arizona where the 2020 election was decided by fewer than 15,000 votes.

(Caption) A pop-up campaign office hosted weekly in Central London by Democrats Abroad provides a base for UK Democrats to write postcards and phonebank to the US, including calling voters in Michigan and further battleground states.

Americans in the UK, including this co-author, have spent the weeks preceding the election participating in an elaborate nonpartisan ground operation to urge Americans – whether students spending a semester abroad or expatriates who have been living in Britain for decades – to take advantage of resources like Vote From Abroad and follow their state’s guidance about the intricacies of overseas voting.

(Caption) Some Americans, including the co-author, have participated in nonpartisan efforts to reach US voters in high-traffic areas across the country, from farmers’ markets to railway stations. Volunteers answer questions about ballots and direct them to overseas voting resources like Vote From Abroad.

These Americans exercise not only electoral, but significant financial sway in each campaign cycle, often sending substantial sums of money in the form of donations to candidates and campaigns, as well as political action committees in the US.

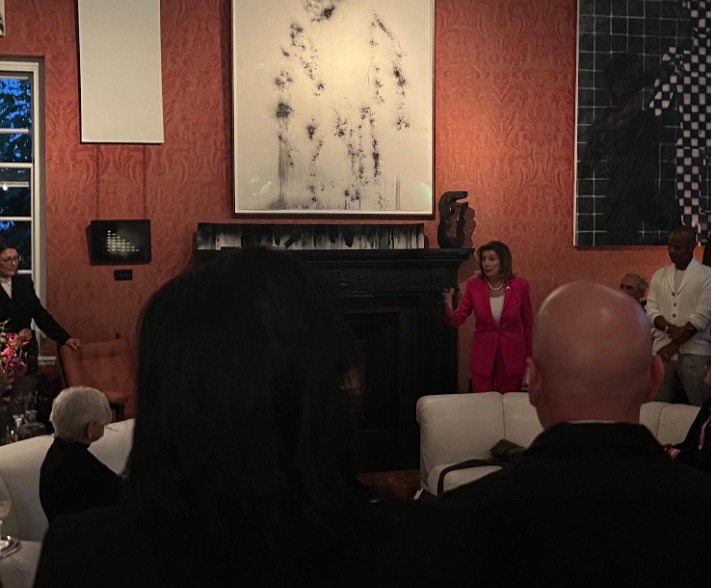

American politics is not only a major source of political activity within the UK. The election itself however is a focal point that materially throws these activities into stark prominence, in a way that average Britons themselves can see more clearly, while simultaneously renewing the commitment of UK-based Americans in terms of their electoral desires. These dynamics are further catalysed by the various high-profile visits to London by key US politicians, including by former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. Pelosi visited the Democrats Abroad campaign office and spoke at a cocktail reception hosted by the powerful Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee for American donors.

(Caption) Former Speaker of the House and current US Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi spoke at a Democratic fundraiser in London on 14 Oct., 2024.

There, Pelosi reminded supporters that the American electorate abroad could not only decide the presidency, but control of Congress – a decisive factor working for or against whoever controls the executive. In doing so, Pelosi conjured up remembrances of the 2018 midterm elections, where Democrats wrestled back control of the House of Representatives from Republicans. “The difference was made by the Democrats Abroad votes,” in the swing districts that ultimately handed her the speaker’s gavel, Pelosi said.

Pelosi closed with a call to action she deemed equally relevant to Americans overseas as to those remaining stateside: “No wasted time, no underutilized resources and no regrets the day after the election.”

As that day approaches, both Britons and their American neighbours in the UK follow the headlines and anxiously await results. From Westminster to the workplace, conversations about the future of the US – and its ramifications for Britain – seem poised to be a staple not only of the coming week, but for years to come.

Meanwhile, many Americans abroad will not be ‘minding their own business’. Whether or not they endorse the Vice President’s election effort, they are likely to agree that one of her most frequently repeated slogans bears truth for whichever party they support: When We Vote, We Win.