#HelloMyNameIs Beth, and I am a third year student children’s nurse.

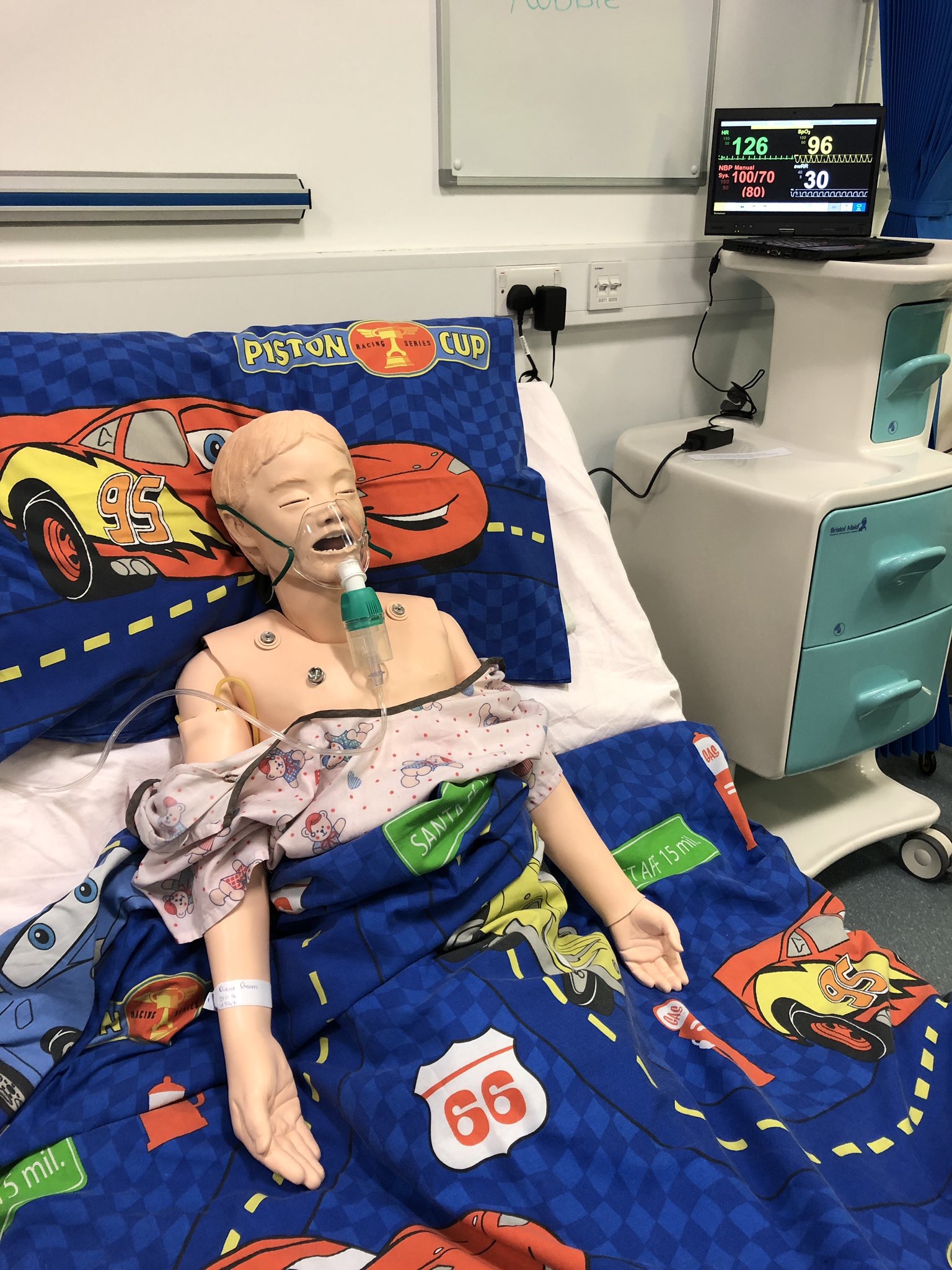

It’s a Wednesday morning, and I’m on shift on a busy general paediatric ward. My patient is a four year old boy with viral induced wheeze. His anxious mother looks suspiciously like one of the tutors at University, and she keeps wandering off to chat to the other parents and make phone calls, but it’s okay because her son is stable now. He’d given me a run for my money after a hairy moment where his oxygen saturations dropped into the 80s and I couldn’t for the life of me find the nebuliser mask despite it being sat right in front of me. But it was fine now. Observations taken, wheeze protocol followed. I’d given oxygen and salbutamol nebulisers, I was drawing up the prednisolone ready to give. Everything was under control. Wow, I was sort of like a real nurse!

“Can I have some help here?!”

Yes, just like on an episode of Holby City. My fellow student nurse is yelling from the bed next to mine, tone slightly panicked. Instinct kicking in, I don’t give my patient as much as a second glance before I run over to the baby who is in cardiac arrest. We start resuscitation, suddenly the little girl’s grandmother is thrust in my direction. She’s distraught. Crying, she asks me if her granddaughter is going to die. We’re doing everything we can, I tell her gently, but inside my stomach is swirling with the adrenaline. We’re all student nurses, I think to myself, we’re winging this!

Somebody comes to take over from me, I can return to my little boy. Giving myself a bit of a shake I plaster a smile on my face as I note mercifully he’s not deteriorated in the time I’ve been away.

“Are these for me to take home? It’s just that they were there at the end of his bed.” his mum says, grasping a bottle of medication.

“Oh, no!” I cry, reaching to take the bottle from her. It was a bottle of prednisolone tablets. When the crash bell went, I’d left them sat on the table by the little boy’s bed, along with a pot of the tablets dispensed out to mix with water. Damn, I thought to myself. I’ve broken every NMC guideline for safe medication administration and it’s not even an hour into my shift.

And then the timer went off.

This wasn’t the shift from hell, thankfully. It was in fact a real-time simulation exercise held at University. The real-time simulation day has become a bit of a legend amongst children’s nursing students here – I remember being absolutely horrified at some of the stories told to me by the third years when I was a first year, only six weeks into my training and hadn’t yet step foot on a ward. If you’re a first year student right now, you would be forgiven for feeling exactly the same when reading this blog post. However, scaring you half to death absolutely isn’t my intention here, I promise! I actually wanted to talk about making mistakes.

In the Cambridge Dictionary, the word mistake is defined as “an action, decision, or judgement that produces an unwanted or unintentional result.” Since I started University I’ve had it indoctrinated into me to always look for an evidence base when you want to say anything and I did the same in this case, looking at a few different definitions in different dictionaries. But this one was my favourite, because the example of the word used in context was very simple:

“I’m not blaming you – we all make mistakes.”

It’s inevitable that we’re going to do things wrong in our lives, but our very nature as health-care professionals means that when we make a mistake in our job, it can feel a bit like the end of the world. I’m not going to pretend that when you do make an error you’re not going to feel awful about it, however much you’re told everybody makes mistakes, but I think it’s important to change our perspectives on mistake-making.

Historically there have been some monumental mistakes made in the NHS – Mid-Staffs, Shrewsbury and Telford, the Northern Irish hyponatraemia deaths, to name just a few of many. However, there have also been significant learnings taken from each of these events. NHS culture was changed irrevocably when the Francis Report was written after mid-Staffs. During my elective placement at Royal Belfast Children’s Hospital, I noted I have never seen more accurate, comprehensive and meticulous fluid balance paperwork.

Demonstrating we have learned from our mistakes is what makes us good practitioners. It is vitally important to debrief and reflect upon events and wonder what we could do differently next time to make sure it doesn’t happen again. The value of engaging in simulation as a student nurse is that you can make those mistakes in a safe environment where it really doesn’t matter if things go a bit wrong, as long as you reflect upon it and learn. In my case, I’ll always remember to take medications with me in my pocket if I’m called to an emergency!

You have probably heard the phrase “I’m going to Datix you!” thrown around in your placements as a threat. The blame culture still exists in the NHS and I think it’s our job as student nurses, a new generation, to accept our mistake making. You want to Datix me, that’s fine. I can demonstrate learning and reflect upon the mistake that I made and I’m not going to beat myself up about it.

I’m going to make the change and be the change.

Author: Beth Phillips, Year 3 Student.

Photograph: @UniS_ChildNurse Twitter

Disclaimer: This blog contains personal opinions of students only and does not necessarily represent the views of the Children’s Nursing team, School of Health Sciences or the University of Surrey.

If you’re interested in writing a blog post for us – whether it’s a one-off about something in Nursing you’re passionate on, or as a regular contributor, please email Beth Phillips (bp00183@surrey.ac.uk), Ellie Mee (em00607@surrey.ac.uk) or Maddie McConnell (mm01664@surrey.ac.uk) – we’d love to hear from you!