Picture that blissful moment when you receive the email finally accepting your paper. Picture those feelings of relief and pride to have successfully addressed even the obscure demands of the infamous Reviewer 2… All those hours of writing, editing, polishing, rewriting; all those weeks waiting for an editorial decision, are finally rewarded.

Let’s face it; these wonderful feelings leave no room for the boring stuff that comes with paper acceptance. Copyright transfer agreement? Licence to publish? Creative Commons Licence? Who cares! Let’s sign the thing away, whatever it says: the article will be out there soon and this is all that matters.

Except—as you will have guessed from the title—this is not all that matters. What we all want, after all, doesn’t stop at publication; this is just the beginning. We want our research to be easily found, widely read and highly cited. And yet it is the tedious jargon on the copyright document that dictates whether others can access and re-use our work.

Three things to look for in a copyright/agreement/licence.

- Do I keep the right to share the paper online?

Most publishers will ask you to sign away the copyright to them. What is important is that you retain the right to share your article online, so that non-subscribers (including non-academic audiences that you may want to reach) can access it, too. This will give you a big advantage when it comes to impact: papers available on open access are much more highly cited that papers that are not. It’s easy to see why—many more people will be able to read your paper—but if you need evidence you can find it here.

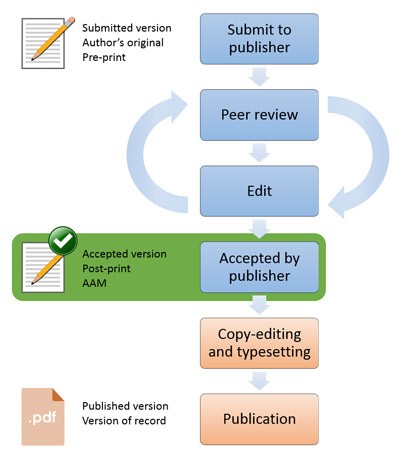

But do publishers allow you to share your paper online? The good news is that many of them do: journals published by most major publishers, including Elsevier, Sage, Springer, Taylor and Francis, Wiley and many others usually allow you to share your own version of the paper (usually referred to as the Author’s Accepted Manuscript; see diagram below). As this is the peer-reviewed version as accepted by the publisher, it has the same content, if not the same format, as the published PDF.

Author’s accepted manuscript. Image reproduced from the REF open access policy FAQs

In short, many publishers allow sharing, as long as what you share is your own version. Too good to be true? Here’s where the small print comes in…

- If I keep the right to share my paper online, when, where and how can I do this?

Most publishers do allow you to share your accepted manuscript online; however, there are restrictions. As every journal has different policies as to the ‘whether, when and where’ of open access, it is important that you read your publishing agreement.

As a general rule…

When. Most publishers do not allow immediate sharing: you can only share the paper after an embargo period, which is usually 12 months after publication for science/technology journals and 24 months for humanities and social sciences journals.

Where. You can share your paper in your University’s open access repository. Sometimes a funder’s repository, like PubMed Central, is also acceptable. However, sites like ResearchGate or Academia are not allowed.

How. Different Universities offer different systems/services to help you share your papers. Here at Surrey we have kept things simple: just e-mail your accepted paper to the Library along with the acceptance e-mail by the journal, and we will do the rest. We will upload the paper for you in the repository and apply the correct embargo, if necessary.

- If I publish open access, can I share my paper anytime and anywhere?

Publishing open access involves paying a fee to the journal. In return, you usually keep copyright and the paper is immediately available as open access. Whether you can share it yourself, and allow others to share it, again depends on the agreement under which the paper is published. The average open access fee is £ 2,000 (higher for some disciplines) so you should make sure that your paper can published under the licence you require, for maximum impact.

Open access papers usually get published under a Creative Commons licence, which specifies how others can re-use your work. The licence you choose depends on how you want others to re-use your work. The most permissive one is the CC-BY licence, under which users can re-share and re-use your paper in a number of ways, even commercially. You can use different versions of the licence if you don’t want adaptations of your work to be shared by others or if you want to restrict re-use to non-commercial. In any case, proper attribution to you as the author is required.

Being aware of the options offered to you by a CC licence is important: you have a say in how others share and re-use your work.

Being copyright-savvy helps us comply with funders.

Many funders including UKRI, the European Commission, the European Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and Cancer Research UK all have requirements related to open access. Some of these requirements are closely tied to copyright. For example, UKRI research councils require open access papers to be available under a CC-BY licence, and the open access policy for REF2021 requires papers to be available in a repository within a specified time period.

Knowing our journals’ policies helps us understand whether we are compliant with our funders’ requirements.

What if a journal does not support open access?

Some journals may not allow open access within the time frames we or our funders require; a few may not support open access at all. In addition, one journal’s policy may be not compliant with, say, both REF and Wellcome Trust requirements. Being aware of authors’ rights is one thing; keeping track of all the details of various policies is, however, a big challenge.

This is where the UK Scholarly Communications Licence (UK-SCL) comes in. This licence ensures that authors retain sharing rights to their publications, regardless of the journal they publish in: the UK-SCL legally overrides any other publishing agreements. The licence has been developed by a group UK institutions, led by Imperial College, and is due to be adopted by a number of Universities in 2019. Surrey is among the early adopters. Once implemented, the licence intends to make authors’ lives much easier.

To conclude…

We should all be aware of what our publishing agreements allow us to do and how they restrict us. This is, of course, important for any other work we publish; not just for journal articles. Monographs, book chapters, research data, portfolios or reports, are all important work that we want others to discover, enjoy, benefit from, cite and re-use. In many cases we may even be able to negotiate copyright. The first step towards this is to be aware of what we are asked to sign in the first place.