Current PhD Creative Writing student Melissa Addey writes about her recent research trip to China.

I should have known there would be trouble ahead when I watched a documentary with my husband about Beijing. The camera panned across the cityscape and I recoiled. “It’s so ugly,” I wailed. My husband laughed. “You’ve got 18th century Beijing in your head,” he pointed out. “It’s not like that anymore.” I knew that, of course, but it was still hard to reconcile the screen’s offering with my imagination.

I should have known there would be trouble ahead when I watched a documentary with my husband about Beijing. The camera panned across the cityscape and I recoiled. “It’s so ugly,” I wailed. My husband laughed. “You’ve got 18th century Beijing in your head,” he pointed out. “It’s not like that anymore.” I knew that, of course, but it was still hard to reconcile the screen’s offering with my imagination.

My PhD is in Creative Writing, for which I will need to complete two components. One is a full-length novel, the other is an academic element of about 30,000 words, exploring some aspect relevant to the novel. I am writing a novel set in 1700s China, a prequel to a novel and novella already written and set in that era. It is the story of a Jesuit priest-painter and a concubine who became Empress Dowager and their relationship with one another as well as with the Garden of Perfect Brightness, the Yuan Ming Yuan. My academic element asks how writers of historical fiction recreate lost landscapes. It includes analyses of other novels in the historical fiction genre to see how their authors have brought past settings to life as well as considering my own work and how the reader might experience the past through reading historical fiction.

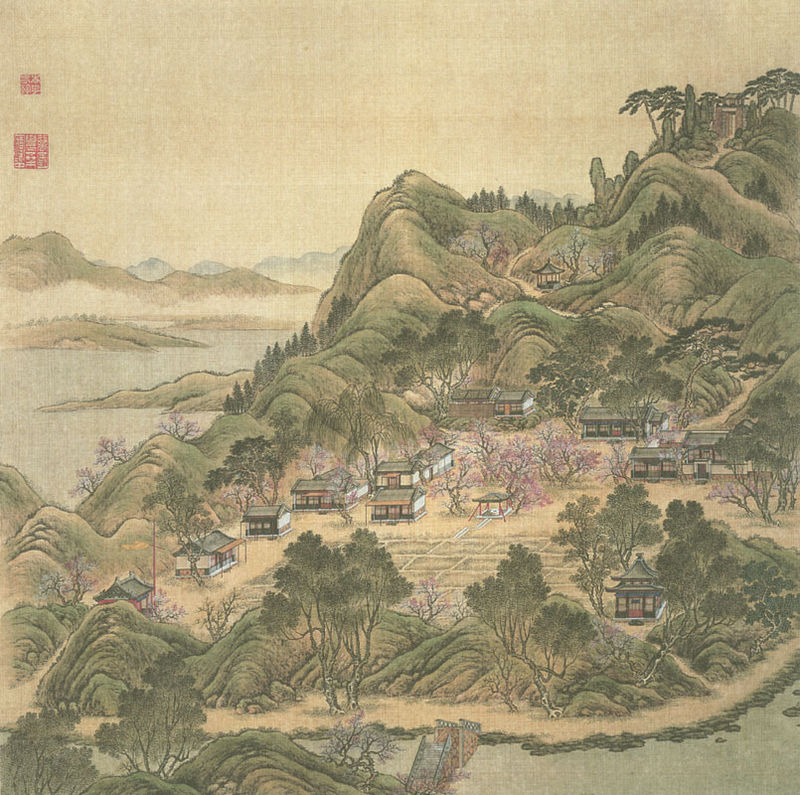

The Yuan Ming Yuan was originally a simple country estate, gifted to a prince who unexpectedly rose to become Emperor. He began to craft the (very large) estate, adding flora and fauna and decorative buildings, using it as a quiet escape from his formal life. His son, the Qianlong Emperor, went on to turn it into the Imperial Summer Palace, every inch of it manicured and shaped to his whims. By the time he had finished its development it included miniature gardens, manmade mountains and lakes, a ‘shopping street’ designed to mimic the real world so that concubines could pretend to haggle with eunuch stallholders, a pretend ‘farm’ (think Marie Antoinette as shepherdess) and gigantic decorative ‘stone gardens’ transported thousands of miles from the south of China. It also had ‘Western Palaces’, created by the Jesuit painter-priest, an exotic European flourish set in the midst of Oriental splendour. Sadly this wonderworld did not make it to the present day unscathed. In 1860, during the Opium Wars, British and French troops burned and pillaged the Yuan Ming Yuan, leaving it a broken ruin for many decades.

Today the Yuan Ming Yuan is a gigantic and charming park, a major tourist attraction in Beijing. Ancient pines mix with flowering cherries, there are lakes, rivers, canals and streams everywhere: it is something like a countryside Venice. Little pleasure boats float you from one island to another. A Western visitor, unaware of its history, would see a very beautiful park. It’s only when you begin to notice odd flat areas amidst the manmade hills, a few tumbled blocks of carved stone, an island containing the foundations for a building that isn’t there that you realise that something is missing: the many buildings that were destroyed and never replaced.

I have been researching this location, amongst others in China, for years. I have seen endless drawings, engravings of how it used to be, CGI reconstructions. I have immersed myself in its history. It is not just a location for the novel I am writing now, I regard it almost as a character in itself. To actually go and stand there was hugely exciting. I had my family in tow: my PhD journey is unavoidably built around two small children, something that can be both a blessing and a curse.

Our first day of sightseeing and we arrived at the Yuan Ming Yuan by about 9am (it opens at 7am). I was excited, ready to see something lovely, camera at the ready, notepad and pen in hand to jot down inspiring writerly thoughts. This was something I’d been looking forward to for a long time.

It didn’t take long to feel disappointment kicking in. My five-year-old son persisted in trying to climb along the rocky edges of deep lakes or wanted to wade into the muddy areas where he had spotted tiny fishes and other things to poke at with twigs. I couldn’t look about me because he seemed in constant peril. When I finally did, there were local Chinese tourists everywhere, blocking scenic views, trying to photograph my daughter (for her blue eyes), wanting to try out their English on us and above all talking (how dare they?), making lots of noise so that I found it impossible to feel the ‘atmosphere’ I’d so much discussed with my supervisors ahead of the trip. Along the delicate winding paths were row after row of vendors, selling tourist tat and snacks. Fake rocks hid speakers which piped out traditional Chinese music, perhaps to give an ‘authentic’ feel to the surroundings. We got lost multiple times, it’s very hard to keep your sense of place when the style of gardening aims to keep you within one scenic view at a time (there is no place within the whole complex where you can see the entire landscape laid out before you).

I snapped. I told off the children, gave up taking photos, got a grim look on my face and started to walk ever faster through the landscape, barely looking at it, ranting at my husband that this whole trip was going to be a disaster: it was unpleasant, impossible for me to get any idea of it as it would have been in the 1700s, it was horrible, commercial, my family was in the way. I was angry and disappointed. If I hadn’t ranted I would probably have cried.

My husband herded the children away and left me alone for a while. When we regrouped they had found a tiny dried-up lake, bereft of tourists but complete with a waterfall of rocks and a flowering cherry tree. The children clambered over rocks that were not perilously close to deep water and I found myself relaxing a little. Thinking about the characters in my novel I focused on the fact that the future Emperor Qianlong grew up in this place. He was a child here. I had my concubines strolling along pathways and over bridges, elegant and poised. But what does a little boy do in such a landscape, princeling or commoner? He finds a twig and pokes at fishes, of course, he climbs over rocks even though his mother begs him not to. My son had inadvertently shown me how my prince would behave in this place.

We left and saw other sights. I studied the layout of the Garden and returned to see the ruins of the Western Palaces. We got up much earlier and had a more peaceful visit. There is only one reconstructed building in the Garden: a stone maze I have used once before in a novel and am about to use again. We walked in it and managed to get lost, which pleased me. I stood where the Emperor would have stood. We sat in a pleasure boat and floated across the lakes, escaping the piped music and experiencing a mode of transport that has not changed much in three hundred years. My husband, a keen photographer, took hundreds of beautiful photos. It was a fun and pleasant place to play as a family.

On my last day in China I returned for the third time to the Garden of Perfect Brightness. I went alone and got up at half past five in the morning to arrive just before opening time. I turned away from the most obvious tourist sections and headed to where the imperial family actually lived during the time my novel is set. There is a small lake surrounded by nine islets, each linked by a little bridge. The whole place seemed to be bursting into bloom. The piped music was silent for the first hour of the day and I heard birdsong. I walked from islet to islet, wondering what it would be like to live there, seeing for myself that you could spot someone you knew even on the other side of the lake, that the tiny streams seemed to divide up territories. I found a place that was once ‘Apricot Blossom Spring Villa’, one of the official Forty Views (scenic spots) of the Garden. It contained tall trees grown up around stone ruins and millions of tiny violet flowers. I sat alone and listened to the birdsong, my writing pad on my knee. I smelt the flowers and felt the lake breezes on my skin. I thought about my lead female character and how she would have seen her home go from the peaceful country retreat of a minor noble family to the decorated and managed Imperial Summer Palace. How she might have missed its birdsong and quietness when she saw the noisy ‘shopping street’ and found the little pathways filled up with servants and officials, courtiers and the many, many gardeners it would take to sculpt the Garden into her son’s lavish vision for it.

I learnt a lot on this trip. I learnt that if you want to look at tourist sights uninterrupted, you need to get up good and early, it makes a huge difference. I learnt that maps and drawings are no substitute for being there, especially if you are spatially challenged like me. Above all I learnt that your own feelings about a place can translate into your fictional world and that the actions of others in a place are worth noting: they may be interacting with that landscape in a way that has escaped you but which may be important for characters in your work.

Beryl Bainbridge, one of the historical fiction writers whose works I am analysing for my academic component, said that her own life experiences helped her to write historical fiction. “(our imagination) must surely grow with us, built from lost conversations and forgotten events, dependent on impressions and sensations which fall through the mind like shooting stars; gathered from fuzzy remembrances of pictures in story books, of wallpaper patterns, fragments of nursery rhymes and Sunday school parables, whispers in the next room, footsteps in the dark, etc. etc.”[1]

My time in the Garden of Perfect Brightness has brought new impressions and sensations with which to feed my imagination in recreating this landscape for a new audience.

Melissa Addey is in her first year of a Creative Writing PhD at the University of Surrey. She writes historical fiction set in 1700s China and you can try one of her books at www.melissaaddey.com/free

Image of the Apricot Blossom Spring Villa, one of the Forty Views of the Yuan Ming Yuan by Shen Yuan, Tangdai, Wang Youdun – MIT, from Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Beryl Bainbridge, 1987, Forever England, BBC Books: UK p.58