“Welcome to the dystopia of dysfunction.”

Taken from the pages of The Swan Book, these words are eerie in the light of the past few weeks’ events. ‘Epic political theatre’ seems to have taken the UK by storm[1]. Among other news, the Government’s most senior advisor has been accused of flouting the Coronavirus lockdown rules, even while showing symptoms of the virus, sparking various debates[2]. Indeed, it seems that the UK political scene has been plunged into a state of dysfunction, one not too far from the fragile, flawed society presented in this week’s novel, The Swan Book.

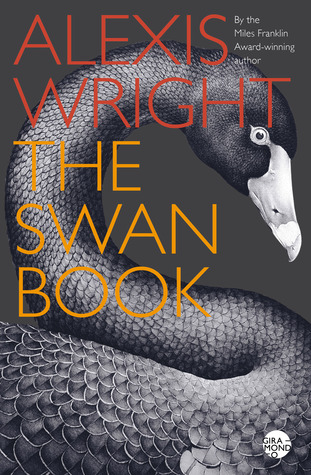

The Swan Book is the third novel from Indigenous Australian author, Alexis Wright. Set in a dystopian future, it follows the story of Oblivion, a mute orphan who is found, cowering in the base of a gum tree. Living in the swampland of northern Australia, Oblivion attempts to navigate the landscape and society of a world that has been irrevocably altered by climate change. This is the novel that my guest this week, Lisa Cosham, has been reading during quarantine. Lisa and I are both Literature students at Surrey, and we travelled Australia together on a study year abroad prior to the Coronavirus pandemic. I’m lucky to have her as my first guest: she’s patient while I try to make sense of my thoughts and translate them into coherent questions.

Lisa and I begin by talking for a while about the current political and social climate. She describes a general state of tension that she feels is spreading across the country, a need for people to ‘stretch their legs’. We agree that hardship of the Coronavirus pandemic seems to be taking its toll on British society. ‘It’s easy to get lost in the tiredness and frustration of lockdown’, she says, ‘especially with the Government’s lack of clarity’.

It’s just as easy to get lost in the rich, evocative language of Wright’s narrative. Lisa explains that ’Alexis Wright uses a lot of metaphor, which can be really intense and a little bewildering’. She feels that this is compensation for the protagonists’ muteness: ‘she can’t articulate her thoughts, she has to do as she is told’. I’m struck here by how this notion, of ‘doing as you’re told’, echoes the sentiments of lockdown and I ask Lisa what she thinks of this. ‘There is so much in there that really relates to what we’re living in now’, she replies, and it’s at this point that she mentions the dystopia of dysfunction quote that I mentioned at the beginning of this post. ‘I’ve been obsessing over this quote; it’s just so accurate for these times.’

And so it is, like much of The Swan Book. To Lisa, there’s something about this novel and the fractured, altered world that it presents that feels familiar. ‘Life as we knew it three months ago, is gone’, she says with a refreshing frankness, ‘people are going to need to come to terms with that.’ I suggest that there is a likeness between The Swan Book and contemporary circumstances because both are just different versions of a bizarre new future that we must come to terms with. The dystopian worlds that once seemed so alien have been transformed. They have become warnings, terrifying possibilities for our own future. Lisa and I agree that the Coronavirus pandemic has shaped the way in which we view these fictional futures. ‘We’re closer to a dystopian future than we think,’ Lisa suggests, and there is alarming truth in her statement.

To me, one of the most fascinating things about literature during the Coronavirus pandemic, is the way in which my understanding of dystopian fiction has shifted. It no longer seems as far away as it once did. As I discussed last week, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four is far less distant than it once was: the Government surveilled society is suddenly very real, very palpable. For Lisa, The Swan Book is the same. These dystopian narratives that once seemed to take place elsewhere are now filled with realism and potentiality, and a global pandemic has proven that. “Fiction” no longer seems to apply. ‘It’s important to confront the ugly possibilities before it’s too late’ Lisa says, and it’s literary texts such as The Swan Book that help us do that.

To close, I ask Lisa what she thinks the future of literature looks like following Covid-19. She tells me: ‘I think we’ll see a move toward reflective writing, almost introspective. I think authors will reflect on the human condition and our behaviours, the way that we reacted and learned to function throughout the pandemic. It’s also very likely that there will be a rise in dystopian and utopian fiction, as a form of escapism.’

As we finish up, I can’t help but feel that Lisa may be correct in her suspicions. It is, indeed, very likely that, with our future so unknown, authors will take to exploring the potential outcomes of the future. It seems that this may be what The Swan Book was to Alexis Wright. An exploration of a potential future, one that turned out to be closer to home than first anticipated. ‘Pandemic literature’ might just be this: twenty-first-century authors writing answers for their unanswered questions.

I’d like to thank Lisa

Cosham for taking the time to speak with me this week. You can find a copy of The

Swan Book, by Alexis Wright on Amazon, if you’re interested. Join me next

week, where I will be talking to English Literature graduate and Surrey Union

staff member, Zachary Zarantonello, about the pressure to be productive during

quarantine and Charles Bukowski’s literature.

[1] Martin Farrer. Who is Dominic Cummings, and why has his lockdown car trip convulsed UK politics? The Guardian. (2020)

[2] Dominic Cummings: What is the scandal about? BBC News. (2020)