“My ambition is handicapped by laziness.”

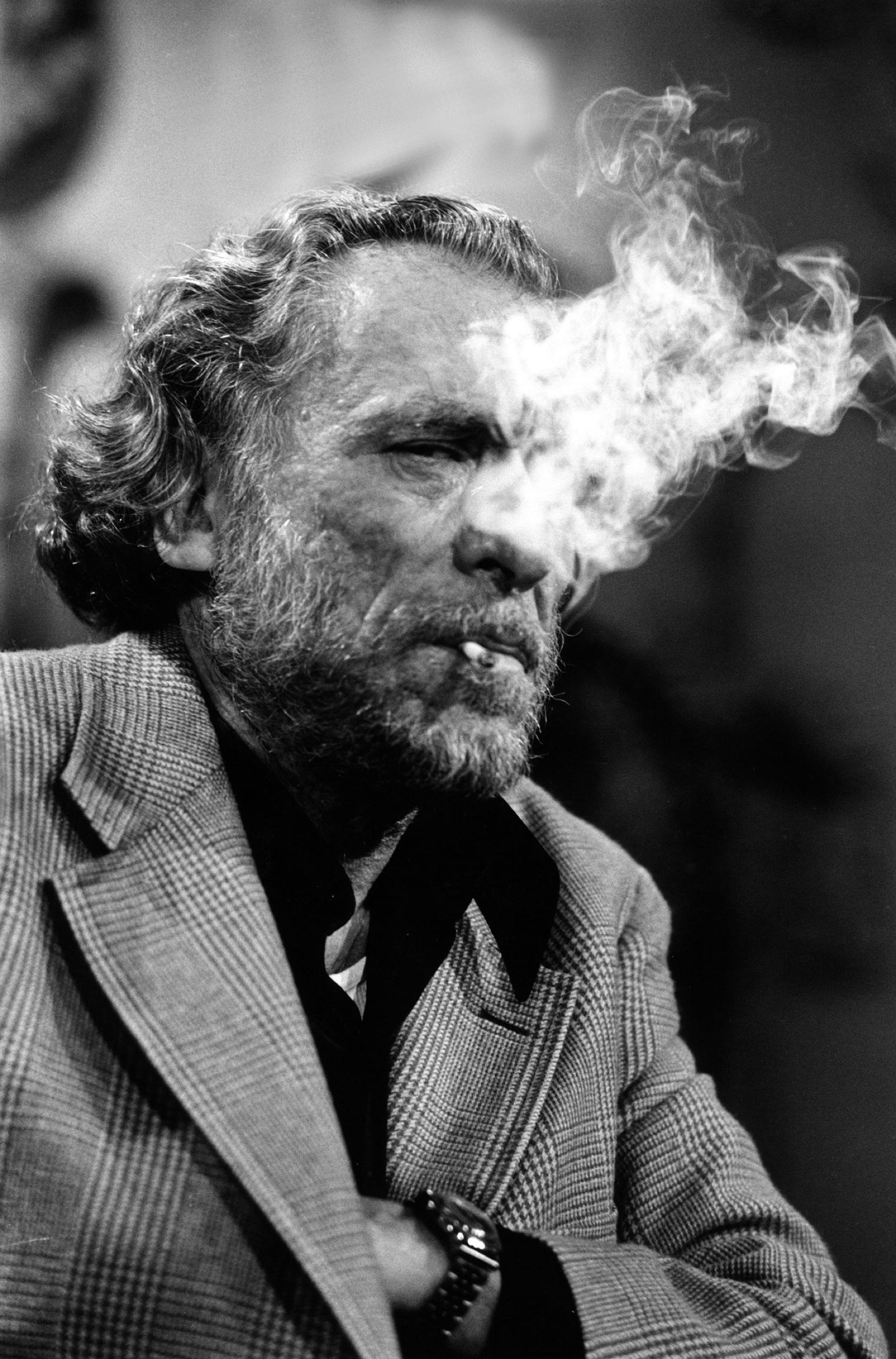

Charles Bukowski: a ‘mythic roughneck’, a ‘brawler, gambler, companion of bums and whores, boozehound with an oceanic thirst’. Bukowski is the author of a wealth of literature, ranging from poetry, to short stories, to full novels. Referred to as a ‘laureate of American lowlife’, and well known for his cynical outlook, Bukowski’s literature is grimy, anti-social and, ultimately, liberated. Though some think his fiction ‘disgusting’, ‘overly simplistic’ and narcissistic, there’s something about this honesty that readers devour. The brutal and self-indulgent candour with which Bukowski writes is what distinguishes him from contemporary writers. It’s also the reason that my guest this week, Zachary Zarantonello, has been reading Bukowski during the Coronavirus lockdown.

I manage to catch Zach after his first day back to work, from home, following a month of furloughed pay. He’s the Video Content Producer for the University of Surrey’s Student Union, and I’ve had the pleasure of knowing him for about a year or so. Zach’s a creative person. He’s an English Literature graduate and a writer. I’ve watched him pore, sometimes for hours, over different graphics and transition effects and title screens for his Student Union videos.

This week, Zach wants to talk to me about creative drive and the pressure to feel productive during lockdown. He describes an internal and external ‘pressure’ to ‘use lockdown productively’. I share his anxieties. It’s been difficult not to feel as if I should be making the most of the free time that lockdown provides. While in quarantine during the bubonic plague, Isaac Newton discovered gravity, and Shakespeare wrote some of his most famous works, including Antony and Cleopatra, King Lear and Macbeth. Zach tells me he feels ‘an obligation, especially with creative endeavours, to constantly improve.’ This notion of obligation feels familiar. Every weekend, I have stared at the unfinished chapter of an unfinished novel that I have been trying to write, willing creative inspiration to strike.

Zach continues: ‘I like to write, I’m constantly trying to improve as a film maker. I think a lot of those that pursue a creative walk of life share in the same romantic idea that we’ll one day create our masterpiece. The thing that puts us on the map as a contributor to our respective art form.’ For Zach, and many others, the Coronavirus lockdown posed a perfect opportunity for such “masterpieces” to be worked on. Finally, we had the free time to learn new skills, try out new hobbies, finish novels. And yet, as Zach says, ‘it didn’t happen.’ The dreams of creative excellence became ‘unassailable goals’. Zach continues: ’I’ve been subscribing to this narrative to an extent, but it’s hard to keep up with the pressure to perform. There have been moments where I have been really good and productive, and, equally, there have been moments where I have done absolutely nothing.’

This is why the literature of Charles Bukowski is comforting. The Bukowski novels that Zach has been reading – Ham on Rye, Factotum, Post Office – indulge in a philosophy of general apathy. The novels are semi-autobiographical in nature, drawing on Bukowski’s own life experiences and beliefs. All the novels have a recurring protagonist, Hank Chinaski, and the character is often referred to as Bukowski’s literary alter ego . As aforementioned, Bukowski was revered as being profoundly cynical. These novels ‘reject the narrative that you should be using free time productively’, Zach explains, ‘[Bukowski] was a bum, a drifter, working a series of menial jobs, a bit of an alcoholic. He’s a bit of a degenerate.’ To Zach, Bukowski ‘indulges in basal desires’. Despite his love of literature, Bukowski does not succumb to the pressure to create, to succeed, to write a masterpiece.

‘Being trapped in lockdown has made me restless,’ Zach continues. ‘I have a desire to go out and experience the world, to live a full, eventful and fulfilling life, something that I really can’t do right now’. Zach is not alone; this desire is the same for most, if not everyone, during lockdown. The cabin-fever, the itch to see friends and family, to visit pubs and climb mountains, to swim in the sea, to meet new people, collect new memories. As Zach puts it, ‘all of that is on pause’. This is why Zach finds Bukowski’s ‘cynical, jaded look at the world oddly comforting’. Bukowski relishes laziness: ’he’s a master of drifting, it doesn’t bother him in the slightest’.

I can see why Bukowski’s novels are reassuring in times like these. The aimlessness, the ‘drifting’ that Zach describes in these stories, all of it feels pleasantly familiar. Lockdown has left many of us confused, lost, directionless, even apathetic. Yet, Bukowski makes this type of inertia his home. He luxuriates in lethargy, he drinks excessively, and, as Zach says, ‘he has no artistic commitment’. In a period of stagnancy, like lockdown, I can see why it’s refreshing to read about a character with such a blatant lack of drive. Adventure-filled narratives, stories of great romances and daring feats, glorious battles, spiritual awakenings: all have the same nostalgic effect. They belong to the outside world. They are unattainable at the best of times, perhaps, but even more so whilst in the confines of lockdown. Though narratives such as these are great forms of escapism, they also hold the ability to remind us of just how trapped we are.

With Bukowski, however, there is none of this. To Zach, there are no ‘fanciful adventures, hard-work, creativity’, because ‘Bukowski is the antithesis of all that.’ The beauty of Bukowski’s literature is the potential it has to alleviate some of our own lockdown guilt. It works to undo the ‘pressure to succeed’ that Zach describes. The hedonistic, half-baked approach to work and life portrayed within these novels encourages us to forgive ourselves for moments of inactivity or a general failure to be productive. Bukowski, in his unapologetic lack of motivation, makes a few quiet days on the sofa seem like nothing. We need only be thankful that, unlike Bukowski in Post Office, whose ‘ambition is handicapped by laziness’, our ambition is only momentarily hindered.

I’d like to thank Zach for taking the time to talk to me. Join me next week for the fourth instalment of Isolation Insight. In the meantime, and as a result of this week’s post, I have just ordered my own copy of Charles Bukowski’s Ham on Rye. I’m looking forward to spending a few lazy days reading it.

Emily Byfield-Riches