To manage plastic waste the UN plastics treaty must be able to measure it, but are current systems for tracking the global trade of plastic trash and the polluting chemicals it contains up to the job? In the first of a new series of blogs, Shashi Kant Yadav explains why the devil is in the detail.

Plastics move. The worldwide plastics trade is massive, with plastics exports reaching more than a trillion dollars or 5% of total trade in 2018. International trade occurs at every stage of the plastics life cycle, beginning with feedstocks and progressing through primary plastics in pellet and fibre form, intermediate plastic goods, final manufactured plastic items, and plastic trash.

Plastics are composed of several chemicals. More than 10,000 chemicals are used in the process of manufacturing plastics to facilitate the synthesis and processing of polymers and to preserve, improve, or add specific properties. Certain chemicals are also produced inadvertently during the plastic manufacturing process as reaction by-products, breakdown products, and contaminants from raw materials and manufacturing processes. Moreover, when plastic trash is exported to developing countries, these chemicals are further broken down into their various components during the recycling and/or dumping process. The variety and complexity of chemicals in plastics can have different environmental and health impacts.

However, the current system of tracking and managing the flow of plastics and their chemical components at the global level does not sufficiently cover all the trade in plastics leading to various leakages of these chemicals into the environment. Thus, it is critical to have coordinated, multilateral action to maintain a database of these chemicals and their migration across different countries to reduce plastic pollution. The Global Plastic Treaty, currently under negotiation phase, can provide a platform for such an action.

Plastics Data: current system

Practically all nations are involved in the global plastic trade, participating at different stages of the plastic life cycle based on their endowment of plastics feedstocks (fossil fuels) or infrastructure (refining capacity; position in global manufacturing chains), or the character of their economies (agricultural or industrial).

The trade data on plastic is maintained at the global level by the United Nations International Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade) based on information reported by more than 170 countries dating back to 1962. The UN Comtrade international data repository is broken down by trading partner and commodity and individual items categorised according to the World Customs Organization’s (WCO) Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS). HS hierarchically arranges data in a code of 2, 4, or 6 digits, where longer codes provide more details on the chemical components of a product.

Primarily, plastics in HS are listed under the two-digit code 39, as ‘plastics and articles thereof’. In 2017, these two-digit codes for plastics were further broken down into 26 4-digit codes (for instance 3909 denotes ‘Amino-resins, phenolic resins and polyurethanes, in primary forms’) and 126 6-digit codes, highlighting further details of plastics being traded. These codes cover plastics from their most basic form (chemical composition) to plastics as finished goods.

Gaps in current system

Since HS is a voluntary process, countries may choose not to provide sufficient information regarding the chemical composition by merely providing two-digit codes and not revealing the chemical composition of the plastic being traded. Thus, the movement of chemicals in the form of plastics is often hidden and very challenging to track.

Moreover, the HS reporting system records only a portion of the actual trade in plastics, as the HS system was not originally intended for product identification at the level of chemical composition. The movement of a significant amount of items that use plastics but which are not classified as ‘plastic products’ (like electronic goods and packaging of cars) is also not recorded under the HS system.

For example, the United Kingdom’s advice to importers and exporters on how to classify their trade products indicates that the crucial criterion is whether the product’s ‘defining characteristic’ is its plastic component or something else. Thus, a product which describes plastics as an associated product will not be registered under chapter 39 of the HS classification system, and the movement of plastics (and underlying chemicals) in that product will go unaccounted for. Thus, raw materials and chemicals used in plastics manufacturing again remain ‘hidden’ from assessments of the movement of plastics as internationally traded commodities or associated packaging.

A way forward

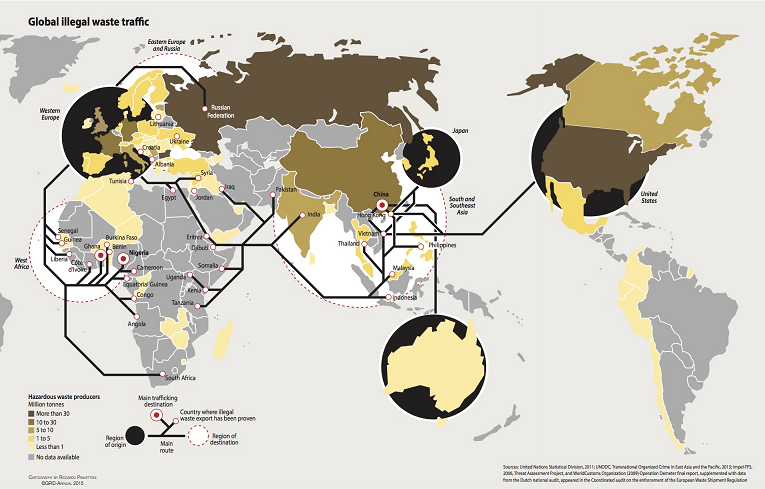

Beginning in 1992 China amassed 45% of the world’s plastic waste until finally in 2018 the National Sword policy came into force prohibiting the import of the vast bulk of plastic waste. The policy shifted the final waste destinations overnight to Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and India, reorganising the global plastics cycle. Further, the COVID-19 outbreak, and the Ukraine crisis significantly impacted the plastics industry. Since 2018, according to the international police organisation INTERPOL, the trade in illegal plastic waste has been increasingly controlled by organised crime, making data collection even more difficult. Plastics are frequently mislabelled, hidden or supplied through indirect channels, producing a carbon impact that vastly outstrips the polymers’ enormous initial worth.

In 2019, the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Waste and its Disposal approved an amendment classifying plastics as hazardous waste, subject to tracking and reporting, in an attempt to stem this plastic tide. However, the United States, the largest producer of plastic waste, is not a signatory of the Basil convention. Moreover, the US Environmental Protection Agency has classed plastic as municipal solid waste rather than a hazardous substance, limiting its border surveillance.

This is where the Global Plastics Treaty provides an opportunity. It can begin by laying down an industrial standard on plastics manufacture which limits the complexity of the chemicals involved in the lifecycle of a typical plastic product. It should also lay down a uniform mechanism to track the movement of plastics and their components across borders. By establishing essential policy measures for collecting and systemising plastic data, the treaty can provide baseline data through which scientists can assess the implication of cross-border plastics trade on the environment and health. This will help in developing science-based precautionary measures to curb plastic pollution. As Kara Lavender Law, an oceanographer at the Sea Education Association (SEA) in Falmouth, Massachusetts, expressed, “You can’t manage the thing you can’t measure”.

The size of the business which is plastics is astonishing. So much greater the enormity of trying to regulate the global trade in plastics – but it must be done.