Möðruvellir in Eyjafjörður. Photograph by Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir

If you drive south from the seaside town Akureyri in North Iceland, you will go along the Eyjafjörður valley, a wide valley flanked by the sea to the north and tall, majestic mountains on other sides. The landscape is relatively gentle in a country known for its rugged volcanic features and towering waterfalls, and although the winters here are long and cold with lots of snow, the area is green and lush in the summer, with plenty of grazing fields for cows and horses. In ca. 30 km you will arrive at Möðruvellir, a typical Icelandic farm with a small but handsome wood church. It stands above the river, overlooking the valley at a point where it forks into two smaller outlets. In such a quiet, idyllic spot, it is perhaps difficult to picture that this remote farm was once a bustling estate with several dozen inhabitants, the seat of generations of wealthy, powerful magnates who had royal titles and offices and belonged to the top layer of society.

The church at Möðruvellir and its eighteenth-century belfry. Photograph by Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir

Möðruvellir was also one of the most prolific centres of book production in late medieval Iceland and several of the fifteenth century’s most illustrious vellum manuscripts were made here. The farm, and probably its scriptorium, was run by Margrét Vigfúsdóttir, a woman who reigned over the district for forty years after she became widowed. Why would a woman pour vital resources into making expensive books? What kinds of texts was Margrét interested in putting down on parchment and what do they say about her?

Margrét was born in Southwest Iceland in ca. 1406 to an aristocratic couple; her father was a governor appointed by Margrete, Queen of Sweden, Norway and Denmark (including Iceland), and her mother counted King Hákon Hákonarson of Norway (1204‒63) among her ancestors. When she came of age, Margrét would have been one of the most marriageable young women in Iceland, and the story goes that when her brother Ívar – who was involved in a quarrel with one of Iceland’s two bishops – was killed in a house burning, Margrét, who narrowly escaped the fire, subsequently vowed to marry only the man who avenged his death. The author of this account may have modelled Margrét on one of the strong, proud heroines of the Icelandic sagas, but we know that in ca. 1436, she married one of the most eligible bachelors of her age, Thorvard Loftsson. His father was a governor and member of the Scandinavian court, so he was a worthy match for Margrét in terms of social status, and he was likely involved in the murder of the same bishop in 1433, so he may have been Ívar’s avenger, at least in Margrét’s eyes. The couple made their home in Möðruvellir in the North and had three daughters before Thorvard died in 1446, leaving a great deal of property to his wife.

We know very little about Margrét’s everyday life or whether her marriage to Thorvard was a happy one, but even if we discount the story about her steely resolve to have her brother avenged, judging from less biased sources, it’s not difficult to imagine her as a force to be reckoned with. When she became widowed, Margrét was forty years old and mature enough not to let herself be pushed around by her relatives or in-laws. Numerous charters show that she was a major operator in North Iceland, buying, selling and managing property. She also donated significant amounts of money and expensive objects to local churches, including ornately carved alabaster statues and luxury textiles. (Please click here to see a newspaper article showing the alabaster altarpiece donated by Margrét Vigfúsdóttir to Möðruvellir church in ca. 1470. It is now in Akureyri Museum.) As a matriarch, Margrét made illustrious matches for her three daughters, celebrated in a fabulous triple wedding at Möðruvellir in 1465. This event was clearly the medieval equivalent of an A-list celebrity or royal wedding, so lavish that it was talked about even almost 200 years later (which is its earliest extant mention in writing).

Assuming that she was equally in control of activities at Möðruvellir, Margrét must have run its scriptorium. There was a long history of book production on Thorvard’s side and this scriptorium was manned by scribes and illuminators who were among the best craftsmen and artists of their time, so Margrét was upholding an old family tradition. Although their works do not rival the most exquisite Icelandic manuscripts from the fourteenth century, the books made by these people – mostly in the third quarter of the fifteenth century (ca. 1450‒75) – required a huge amount of material resources, expertise and time.

What texts do these expensive books contain and what function did they serve? Their contents are eclectic and there was something for everyone at Margrét’s estate. Some of the manuscripts are like modern day paperbacks, small and plain books crammed full of riveting stories about knights or Viking heroes. They would have kept the farm’s many inhabitants and guests of different ages and walks of life entertained through the long winter nights and at feasts. Another is a decorated lawbook containing secular and church laws, the kind of book anyone who had power and property had to own.

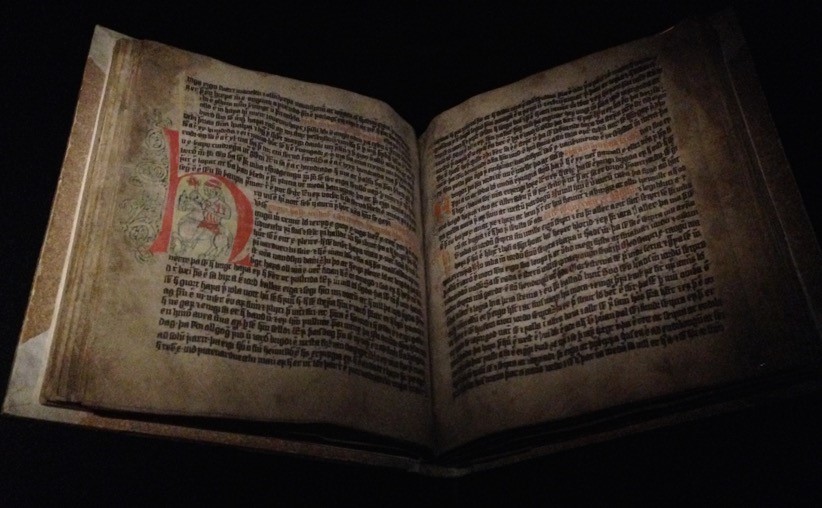

A mid-fifteenth century lawbook. Reykjavík, Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, AM 132 4to. Photograph by Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir

A third book found at Möðruvellir was the so-called Icelandic Book of Drawings: artists working in the scriptorium would have used the models as templates for decorations.

Saint George and the dragon. From the 15th century Icelandic manuscript AM 673a III 4to in the care of the Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland. The Icelandic Book of Drawings was a book with models or templates for artists who illuminated manuscripts. It is badly damaged but it is the only book of its kind from Scandinavia to have survived to modern times. Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.

Other books from Möðruvellir speak to more unusual interests, and they were also larger and finer than most manuscripts produced in the country at the time. First, one book contains the saga about the reign of King Hákon Hákonarson, Margrét’s ancestor, as well as two other sagas about Norwegian kings. Judging from a second codex, Margrét had an interest in literature popular at the king’s court, i.e., translated romances originating in France and England – imparting the values of chivalry and crusades – as well as original Icelandic compositions adapted from or written in imitation of these texts. A third book preserves an original text written at the Norwegian court, the King’s Mirror.

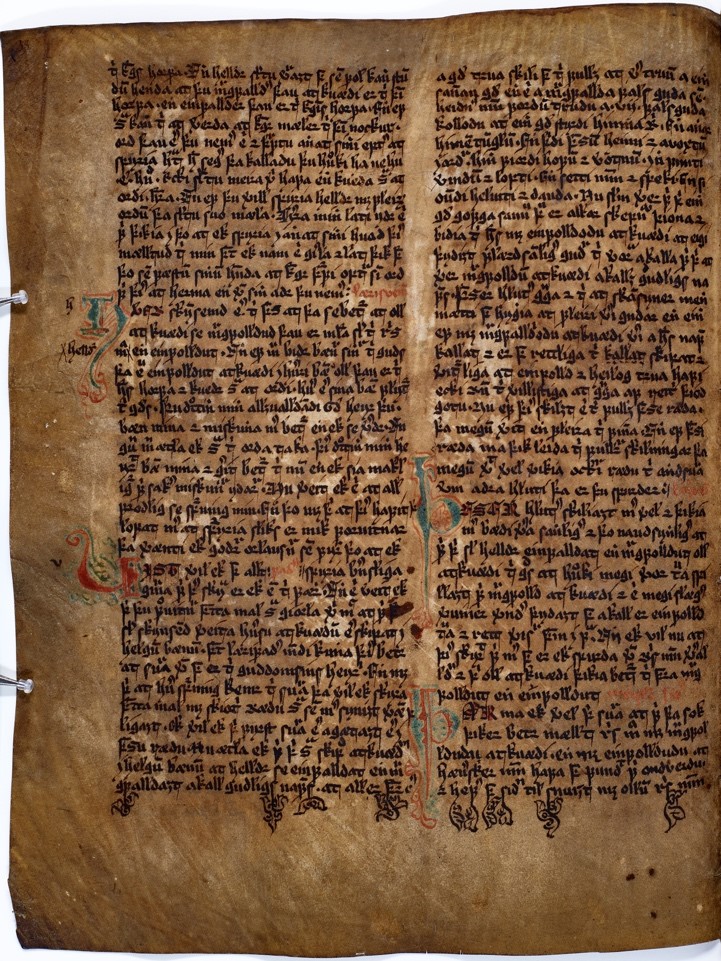

Leaf from the King’s Mirror. Copenhagen, Arnamagnæan Collection, Copenhagen University, AM 243 a fol. Image reproduced with permission of the Arnamagnæan Collection, Copenhagen.

The text, probably written for King Hákon’s son, is a learned, encyclopedic treatise about subjects including natural phenomena, Christian ethical behaviour and courtly etiquette, and there is a section for merchants with advice about how to outfit a boat and succeed in business. Many of the texts gathered in these three books had seemingly not been popular for many decades before they were written down at Möðruvellir but Margrét’s interest in the King’s Mirror may be the reason for a subsequent spike in its popularity: more than a dozen books or fragments containing the text are preserved from the following decades. The physical size of the books might also have played a part in this development, further indicating the texts’ prestige in Margrét’s eyes. Large, decorated volumes such as these were display books and status symbols, just like an expensive piece of furniture or a car nowadays.

Although she let the household have their entertaining but, at times, vulgar stories, no one who came into the living quarters at Möðruvellir would have missed the large and thick volumes with the saga of her ancestor, King Hákon, and the literature he favoured. By cultivating the king’s literary interests, Margrét wasn’t making books for reading in private. She was crafting an identity to project to the outside world, whether to neighbours, relatives, friends or rivals. The texts in these two luxurious books align Margrét with King Hákon, expressing to the community that she is of royal blood, has royal interests, and should therefore have top status in society. In other words, Margrét was saying, with her books, that she’s no arriviste trying to impress her social superiors, but, rather, people should aspire to her tastes and values. Just as Queen Margarete, the monarch who appointed her father to his office, managed to fulfil a leadership role despite her gender, Margrét’s status was based on her wealth, noble lineage, cultural capital and perhaps an assertive, charismatic personality. Through her match-making and feast-giving, patronage of churches, and above all, book production, Margrét Vigfúsdóttir of Möðruvellir, if not actual royalty, emerges as a queen of books who made a lasting mark on Iceland’s cultural heritage.

The research leading to these results has received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under REA grant agreement no. 331947.