The Crucifixion, Pietro Lorenzetti (1320-44), tempera and gold leaf on wood. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift and Gwynne Andrews Fund, 2002).

Images and stories of bloodshed have been ubiquitous of late. Bloodied and wounded children in Syria are carried towards hospitals by wailing parents after being exploded by man-made weapons. Blood supplies are being transported by drones in Rwanda to rural medical clinics where five hour journeys have been sliced to 30 minutes: a life-saving operation for patients like postpartum, haemorrhaging women, who represent a massive proportion of mortalities in this region – not dissimilar to the Middle Ages, when postpartum deaths were commonplace.

Donated blood supplies. Wikimedia Commons

In the Middle Ages, the power of blood-images was just as immediate. Yet, whilst the value of blood – the very essence of our fluid vitality – is almost taken for granted in its pulsating, energising potency, we continue to wonder upon, to gaze on, to almost fetishise, escaped blood.

Lost blood.

On a simple level, of course, lost blood signifies death. This explains, to a great extent, the human fascination with its aberrant appearance outside the body. Lost blood equals lost life.

But does it always? In medieval culture, blood was just as powerful in its iconographic symbolism, largely in the context of Christ’s crucifixion. Paintings and illuminations of Christ on the cross often emphasise the complete exsanguination of his body. His blood pours continually in a paradox of timeless velocity. Hanging, in corporeal entropy, Christ is depicted as dry and discoloured.

The Crucifixion, Pietro Lorenzetti (1320-44), tempera and gold leaf on wood. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift and Gwynne Andrews Fund, 2002.)

These were the physiological signs of a bleeding, dying body in medieval medical texts. The scientific ‘signs of death’ were not only the domain of the physician, but also the priests, hospital nuns, and even christen of the community who enacted death bed vigils. Both medic and priest were equally qualified to diagnose such ‘signs’ (which also included a ‘sharpened’ nose, shallow breathing, and tightness of the skin), not least because the border of medicine and religion in the Middle Ages was blurry to say the least. For example, in Cannon 22 of the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, Pope Innocent IV went so far as to declare that a priest should be called before a physician in cases of near-death. The health of the body and the soul were interrelated, but the soul’s health took precedence, for eternal life was of the greatest import:

As sickness of the body may sometimes be the result of sin… we by this present decree order and strictly command physicians of the body, when they are called to the sick, to warn persuade them first of all to call in physicians of the soul so that after their spiritual health has been seen to they may respond better to medicine for their bodies.(Cannon 22, Fourth Lateran Council, 1215).

Images of the Passion resonate even more at this time of year, when the remembrance of Jesus’ birth is simultaneously celebratory and devastating: born to die a martyr’s death, the hope-filled tableau of the nativity scene is undercut by the dreadful subtext of Christ’s predestination. There is a terrifying continuity between the parturient blood of birth and the salvific blood of the crucified Christ.

Margery Kempe, one of the medieval mystics of greatest renown, was notorious for her bothersome crying and noisy piety (how dare a woman be so loud?). But despite her neighbours’ grumbling and irritation at her interruptions during Mass and her moral postulating at dinner parties, they hastily retract their annoyance at times of their relatives’ dying; actively requesting Kempe’s presence at the death-beds:

Also þe sayd creatur was desiryd of mech pepil to be wyth hem at her deying & to prey for hem, for, þow þei louyd not hir wepyng ne hir crying in her lyfe-tyme, þei de[sir]ryd þat sche xulde bothyn wepyn & cryin whan þei xulde deyin, & so sche dede. (BMK, Bk I, Ch. 72).

[Also, many people desired to have the said creature with them at the time of their death and to pray for them, because even though they did not love her weeping or her crying during their lifetimes, they desired that she should both weep and cry when they came to die, and this she did.]

Though there is satirical potential in the people’s desire to reclaim Kempe’s bothersome crying performances and to utilise this ebullience for their own dramatic end (quite literally), Kempe happily complies. To have watched the deaths of her fellow parishioners time and time again would have given her a familiarity with the ultimate transition from this world to the next, greater even than the average medieval person, whose contact with death was ordinarily frequent.

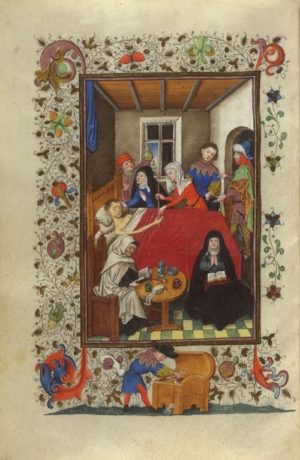

Death bed scene from The Hours of Catherine of Cleves. The Morgan Library MSS M.917, p.180 – M.945, f.97r. Reproduced with permission.

Not all medieval deaths involved blood loss, of course. But, as Caroline Walker Bynum, Liz Herbert McAvoy, Peggy McCracken, and Bettina Bildhauer have demonstrated, blood was a central facet in the devotion, health, generation, and gendering, of medieval life.

Much has been written about the symbolic value of female menstruation. Since Eve’s transgression, women’s blood has been associated with impurity and (wo)man’s fall from grace. In the Middle Ages, menstrual blood was considered toxic: women who ‘retained’ this blood because of ill-health or age could injure small children or curdle milk just with their gaze. Medieval gynaecological texts prioritised regular menstruation as a crucial indicator of female health. If menstrual blood was inadequate, measures were taken to stimulate its activity. If bleeding was excessive, it was counteracted through phlebotomy or the drawing of the blood to other parts of the body using heat, or cupping.

But at the same time, menstrual blood was necessary for fertility, as the author of the Liber de sinthomatibus mulierum, one of the twelfth-century ‘Trotula’ texts, outlines:

The common people call the menses “the flowers”, because just as trees do not bring forth fruit without flowers, so women without their flowers are cheated of their ability to conceive (The Trotula, trans. and ed. Green, p. 72-3).

The Benedictine abbess, visionary and healer, Hildegard of Bingen (d.1179), even prescribed menstrual blood as a cure for leprosy, to harness its fertile and nourishing potency:

If a person becomes leprous from lust or intemperance… He should make a bath…and mix in menstrual blood, as much as he can get, and get into the bath’ (Physica, trans. Throop, p. 61).

While male lost blood was associated with valour and usually aligned with Christ’s ultimate sacrifice or the courageous spilling of blood by knights or warriors on the battlefield, female lost blood demanded wariness, sometimes repellence, but it was also profoundly necessary.

But what about the stage of life when women lose blood in a different way?

During the menopausal years (another middle age, perhaps), medieval women have been shown by scholars like Anneke Mulder-Bakker to become more male; to gain authority, status, and the credibility to write and to teach (if not to preach). It could be suggested that women of this life stage were more authoritative because they had lost the menstrual blood that had previously defined them as stained and polluted. No longer the antitheses of the Virgin Mary, whose own gestational and menstrual blood was regarded by theologians like Thomas Aquinas as pure because of the operation of the Holy Spirit, women could identify in different ways, post-menopause.

In my doctoral thesis, I investigated Margery Kempe’s menopausal years in this very light. How was she ontologically and experientially different, after the lost blood of menopause? What was the meaning of losing the very blood that medieval culture loaded with so many different meanings?

One of my most interesting findings was the correlation of the end of Kempe’s ten years of boisterous crying with the age at which most medieval medical texts situate the onset of menopause: around fifty. Kempe received the gift of tears at Mount Calvary in Spring 1414, aged forty-one. This violent style of weeping lasted for ten years ‘ϸis maner of crying enduryd ϸe terme of x ȝer’ (BMK, Bk. I, Ch. 57) until she was around fifty-one, after which point her tears became softer and quieter. Is it coincidental that her loss of blood – the excessive superfluity that medical texts suggest is absent after menopause – coincides with her loss of boisterous tears? Now characterised by less excess, Kempe was more measured and balanced, free to heal and to minister.

Liz Herbert McAvoy has identified the way in which anchoresses, and those in monastic enclosures, practised regular phlebotomy [blood-letting] to regulate their bodily health. These practices were stipulated by Rules such as Ancrene Wisse. Such deliberate blood-letting, far removed from the bloody curse of Eve, allowed religious women to regain control of their lost blood and to harness it for the health of their body and their soul.

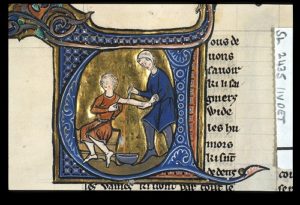

Blood-letting in Aldobrandino of Siena’s Régime du Corps. British Library, MS Sloane 2435, f.11v. France, late 13thC. Wikimedia Commons

So, what, then, is the meaning of the lost blood of the Middle Age?

Today, it is primarily (and understandably) a symbol of wounded-ness in the pejorative sense. In the Middle Ages, however, the meaning of lost blood was multivalent, transferable, and, ultimately, salvific. That blood increased in value in medieval culture when it was on the outside – escaped, and lost – reveals how medical and spiritual ideologies were interrelated. The exsanguinated body (purified for God), is a body that is bled in union with Christ. Such a body is not weakened, but strengthened by the plurality and potency of blood’s life-giving substance: even if that life is necessarily of another world.