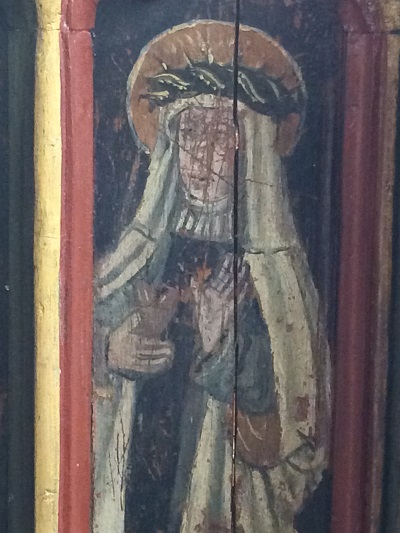

An image of St. Catherine of Siena from a 15th-century roodscreen at Holy Trinity Church, Torbryan, Devon (my photograph)

The Middle Ages was not devoid of women in politics. Women ruled kingdoms, they waged war, they managed armies and households and fiefdoms in their husbands’ and fathers’ absences. But most of these women were “to the manner born,” as Shakespeare has written, and, “to the manor born,” as the phrase has been reinterpreted to mean. They were aristocrats, born into and married into ruling families and families of power. Their power afforded them the ability to wield it as women in a culture that generally did not like women in their politics.

But what about the “average” medieval woman? Or at least the average, educated, upper class woman? Although my interest in Catherine of Siena was initially driven by work on holy women and devotional culture, Catherine was not just a holy woman, she was a politician. And both roles — holy woman and politician — were roles that bothered the men in power all around her.

I am finishing up a book about Catherine entitled Fruit of the Orchard: Reading Catherine of Siena in Late Medieval and Early Modern England, where I examine the ways in which texts by and about Catherine were excerpted, glossed, and circulated in England. In nearly all surviving English manuscripts, Catherine the holy woman takes precedence over Catherine the politician.

One translated text, however, shows how the two sides of Catherine were inextricable, and how troubling the politician side especially was to the Church. Stephen Maconi, one of Catherine’s main followers, wrote a letter in support of Catherine’s canonization that is anthologized in a manuscript eventually housed at the Beauvale Charterhouse: Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Douce 114. Catherine’s mystical qualities are mostly absent from Stephen’s letter. It is written in response to suspicions about her holiness, responding to the criticisms her legacy faced after her death. As Prior General of the Carthusian’s Grande Chartreuse during the schism, he carries an especially weighty authority for his monastic readers.

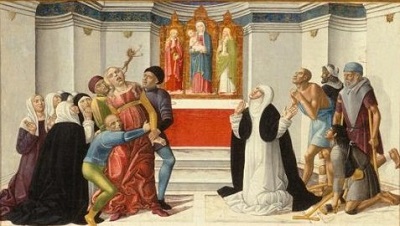

St. Catherine of Siena Exorcising a Possessed Woman, Denver Art Museum. Image from Wikimedia Commons

Stephen’s letter is intended to support the bid for Catherine’s contested canonization, and part of his agenda aims to assure his readers that Catherine’s powers were authentic and divinely inspired. While the letter reaches England nearly simultaneously with Catherine’s eventual canonization, it is written when such an outcome was far from a sure thing, and the tone of the letter — the defense — would have helped authorize women’s visionary texts generally and Catherine’s more mystical literature specifically. The letter was not a routine hagiographic recounting of a saint’s miraculous abilities, but rather the justification of that sainthood. Catherine’s follower and the author of several texts concerning Catherine, Thomas Caffarini, had started the wheels in motion for her canonization soon after her death in 1380 and in earnest in 1398 in Venice, where he was based after he had founded there and become director of a convent of Venetian mantellatae (the Dominican third order to which Catherine belonged).

He had moved some of her relics to Venice and was celebrating Catherine as a saint in fact, which promoted her opposition to demand a full investigation of her veracity and possible sainthood. As noted earlier, Il Processo Castellano lasted from 1411-1416, so Stephen’s letter is one of the first entries into what would become its corpus, dated at 1411. This bid was unsuccessful and she was not canonized until much later, but it is this “quarrel at Venice in the Bishop’s palace against the canonization of this virgin” which has prompted Stephen’s testimony (my translation from the text in MS Douce 114). He recognizes that it is a “quarelle” (querele in Latin, which can also mean “grievance”) in which he is participating, and he is offering evidence to be used within that debate. The factuality of his account is actually important to his readers and he knows it. Stephen’s writing represents the process of making Catherine into Saint Catherine.This has the dual purpose of addressing Stephen’s original audience’s concerns about Catherine as saint and the later English audience’s anxieties surrounding women’s visionary texts.

Stephen spends some time on Catherine’s miraculous abilities, powers that her hagiographer Raymond of Capua had largely ignored. For example, he is careful to explain what happened during her moments of ravishment where she would become transfixed, stiff, and unmoving: “She was suddenly ravished throughout her body, staying there without moving or feeling as if in prayer. She was enraptured like this each day, as we ourselves witnessed. Not a hundred or a thousand times, but much more frequently. Her limbs stayed still, stiff, and unmoving, so that her bones would have broken if her limbs were bent.” Stephen’s intent of convincing his audience of miraculous activities in Catherine’s life, thus making her worthy of reverence and sainthood, reveals itself in its repetitive reference to witness and amazement. Catherine’s ravishment, which causes such stiffness in body her bones seemed literally about to break, was seen by “ourself,” and not merely once, not even hundreds or thousands of times, but more frequently. Catherine’s miraculous state is in fact her normal state of being.

St. Catherine of Siena besieged by demons, National Museum in Warsaw. Image from Wikimedia Commons

In addition to emphasizing the validity of his account, Stephen strives against a perception of Catherine as too political, too mobile, too outspoken, and yet emphasizes this aspect of Catherine’s personality in doing so. Stephen frames his discussion of Catherine at a centrally political event in her life, the trip to Avignon to convince Pope Gregory XI to return to Rome. He insists on Catherine’s piety on the trip, not her purpose, and dwells on her overall devotional purity.

In order to convey her impressive devotional power, Stephen emphasizes her communication with important men and her ability to impress them. In one episode three advisors of the pope, including an archbishop, go to confront Catherine and prove that she is unworthy to speak to him. The status of the men is not incidental, indeed, Stephen recounts that the Pope’s doctor tells him that “if the arrival of these three men were put on one side of scale and the arrival of all other men in the court of Rome were on the other side, the three men would be much heavier.”

The men who come to question Catherine are most concerned at her audacity in speaking to the Pope about political matters; her purpose there, to convince the papacy to return to Rome from Avignon, is never explicitly mentioned. They say to her: “We have much marveled since you are a vile little woman who wants to speak of a great matter with our lord the Pope.” Catherine’s status as a “vile little woman” is contrasted to the “great matter” of which she speaks. Gender, and the fact that women should not be politically engaged, is clearly the qualifier that is upsetting the bishops most, here, not her visions.

The men test Catherine, clearly suspicious of both her abilities and her intelligence, shaming her confessor who cannot answer the logical questions they pose, while Catherine (just moments before described by the questioners as a “vile woman”) does so deftly. She teaches without preaching, demonstrating her theological and intellectual superiority to the Pope’s advisors, while maintaining her humility:

They asked her a great many questions, especially about her ravishment and her unique manner of living. And since the apostle says that the angel of the devil transfigures himself into an angel of light, how she knows she is not being deceived by the devil. They asked her many other questions. And the debate lasted into the night. Sometimes Master John, her confessor, would answer for her, and though he was a master of divinity, nevertheless they were so mighty that they confounded him with a few words, and told him “You should be ashamed to say such things in our presence. Let her answer, for she answers much better than you do.” At last, they went away both edified and comforted, telling our lord the pope that they never found a soul so meek and enlightened.

Of course, the test these Roman bishops bring to Catherine begs the question that a man would not have been subjected to such rigors. They begin their assault on Catherine for being a “vile little woman” because of her audacity in even seeking the Pope out and daring to speak on “great matters.” Catherine persists, though, and she wins the day not because of her more lauded abilities (her ravishment, her prophecies), but her nuance of speech, her ability to follow the complex theological questioning of the men who doubt her.

Altarpiece showing St. Catherine of Siena, Dominican Convent, Taggia, Italy. Image from Wikimedia Commons

Catherine is ultimately successful in convincing the Pope (Gregory XI) to leave Avignon and return the papacy to Rome. She is frequently credited for this move along with another woman visionary whose life was equally political and devotional, Bridget of Sweden. Later, theologians such as Jean Gerson would blame these women and their visions (decried as false) and the men who were swayed by them, the pope especially, for the schism that follows shortly after the move back to Rome. Bridget and Catherine are pointed to again and again for what happens when you listen to women in politics, a cautionary tale. But as Stephen’s account shows, Catherine was resolute and savvy; she turns the men who see her as “vile” to ones who feel “edified” in her presence. She persisted.