Image from The Taymouth Hours, BL Yates Thompson 13, f.68v

I am quite convinced that if you scratched most writers of medieval fiction, under the surface you would find a childhood spent reading stories about the middle ages: Robin Hood, Arthurian Myths, Fairy Tales. Perhaps you would also find a longstanding love of medieval imagery and symbolism, the pictographic shorthand for saints’ lives and biblical tales.

As a child, I devoured such stories, and I loved decoding medieval artworks. It was so satisfying to know that if the female saint was holding a tower, she was St Barbara, if a wheel or a sword then St Katherine and, if there was a gridiron, poor St Laurence. I felt like I’d learned a secret language. When I decided to study Archaeology at University, I expected it would have a bit more mystery and symbolism in it – a bit more romance and a bit less mud. Ah well. I had reckoned without the British weather.

My later career in museums allowed me to indulge those narrative interests, as each object has innumerable layers of meanings. But when I came to write my first novel, The Errant Hours, the influence of my early love of archaeology was still strong. Archaeology, in the main, looks at the discarded and unwanted remains of daily life, the broken things most people do not consider important.

In The Errant Hours, I wanted to uncover what life was like for the people who did not make it into the history books – to explore the daily lives of people who lived in the distant past, and to understand how their circumstances affected their fears, hopes and beliefs.

And certainly the large numbers of nails, bones and potshards I found on archaeological sites helped me do that, and to flesh out the characters’ habits and habitats. But it would not have been a very satisfying book without another ingredient.

People of the Middle Ages lived not just in a physical environment but in a spiritual and social one, and one of the most lasting and powerful elements of these medieval ways of thinking are the religious and secular stories that were commonly known and shared.

You may be familiar with the way Christian ideology at the time tended to characterize women as virgin/saint, mother/wife or whore/temptress. There are lots of influential medieval stories about saints and whores, and not nearly as many about wives and mothers. The first part of The Errant Hours explores the interesting relationship between a holy virgin and mothers in the legend of Saint Margaret of Antioch. The second half of the book explores the wife/whore relationship through the legend of The Lady of the Well/The Knight with the Lion, which I hope to blog about later in the year.

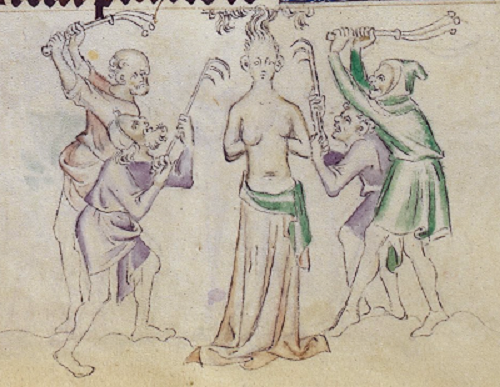

Most female saints were either martyrs or nuns, but the virgin martyrs seem to have been most popular. Looking at the passions of these saints in compilations such as Voragine’s The Golden Legend, I was struck by the similar outcome for young women who refused to have sex with powerful men: generally torture followed by death.

St Margaret of Antioch being tortured. BL Royal 2 B VII f. 308v (public domain image)

In some cases a miraculous return to life is achieved (eg. St Winefride) but then the woman goes on to become a nun, not to a ‘normal’ family life.

However in the case of St Margaret of Antioch, there is a nod to marriage and motherhood in her story, through a quite unexpected agency. And this interested me because, although some medieval women did become nuns, most women were not wealthy enough. The vast majority of ordinary women married and became mothers, or died trying.

St Margaret being shoved into prison, and later emerging from the dragon, who is still chewing on her dress. BL Yates Thompson, MS 13 f 086v (public domain image)

According to the legend of her martyrdom, Margaret of Antioch (known as Marina in the Eastern Church) was a virgin convert to Christianity in the early 4th Century AD. Her father was said to be a priest of Jupiter, who disowned her after her conversion. She spent some time as a shepherdess, (a nod to her humility and sacrificial innocence) and then was abducted by the Roman Governor, Olymbrius, who wished to ‘marry’ her. When she refused, he had her tortured in numerous gruesome ways.

While all this was going on, she was also attacked by the devil in the form of a dragon (even Voragine reckoned this part of the legend was apocryphal, but that didn’t stop the dragon from becoming Margaret’s attribute). The dragon swallowed her, but when she made the sign of the cross its belly burst open and she came out ‘unharmed and without any pain.’ Voragine then describes how she was beheaded in front of the Governor – and before the final blow she made several appeals to God, including that those who prayed to her and read the story of her passion would be safe in childbirth and bring forth healthy infants.

And so, in accordance with medieval logic, because of these promises and because St Margaret had come out of the dragon’s belly unharmed, she became the patron saint of childbirth.

As I was researching medieval childbirth, I came across a manuscript that not only evidenced this belief, but also provided moving and tangible proof of the spiritual practice of medieval women. British Library MS Egerton 877 – The Passio of St Margaret, 14th century. Once I had read the translation of the text and the fascinating explanation, I knew straight away: this was the touchstone of my story.

This special manuscript is an Italian copy of a book that would have been very common in England, but which did not survive the reformation: a description of the horrific torture of a virgin that was designed to be a birthing aid – to be read out to a woman in labour. The story is a standard version of the life of St Margaret – but the final pages are extraordinary.

They consist of a series of prayers that would have been read to the woman in labour, including this entreaty to the unborn child:

“Come forth. If you are male or female, living or dead, come forth for Christ summons you, in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, amen.” (translated by Prof. John Lowden, Courtauld Institute)

But it is the final illustration of the birth chamber itself that gave me the eerie feeling that I was in the presence of the past.

The Birthing Chamber – BL Egerton 877 f. 12 (public domain image) The text says: “The Father is alpha and omega, the Son is life and the Spirit is medicine. Thanks be to God”.

In this image we see the mother who has just given birth lying in the bed, and the midwife holding the swaddled infant. On the right, I believe that the figure under the canopy is Saint Margaret. Holy people are often given this architectural device. But the paint on this side of the page is so smeared and distorted through repeated kissing, it is hard to make out the full figure. As Professor Lowden says in his description:

How many times was this page devotedly kissed by women in fervent hope that their childbirth might leave them ‘unharmed and without any pain’? And if the worst happened and their child was stillborn how many women prayed in anguish, with the help of this little book, that their labour might still end safely?

Through this poignant trace of desperation, I could imagine myself into the lives of these women, even as I remembered the birth of my own son, after a long, stalled labour that would have killed us both in the thirteenth century. I started thinking about the consequences of the large number of deaths in childbirth, and particularly what would happen to a surviving baby whose mother had died. And so the plot began to take shape in front of me, like a detailed picture being drawn before my eyes.

The Errant Hours begins in that final illustration, with the difficult birth of the heroine of the story, Illesa (‘unharmed’ in medieval Latin) in 1266. The action continues when she is a young woman and her midwife mother has recently passed away leaving her a richly decorated book, a Passion of St Margaret, which, as a poor woman, she should never have possessed.

The Errant Hours is an adventure, following Illesa as she struggles to save her brother and herself in the face of poverty, violence and corruption. But it is also the story of a daughter who loses and finds a mother, the story of a sacred book believed to have the power of life and death, and the story of how a young woman negotiates the physical and spiritual dangers of Plantagenet Britain, and survives to come of age.

These stories intertwine, bind, resist and console each other, as all our stories do.

Kate Innes

****

Kate Innes was born in London and raised in America, returning to the UK in the 1980’s to study Archaeology. She taught in Zimbabwe before completing an MA and working as a Museum Education Officer around the West Midlands. She now lives in Shropshire. Her first novel, The Errant Hours, has been added to the reading list for Medieval Women’s Fiction at Bangor University. Kate has been writing and performing poetry for many years. Her collection, Flocks of Words, was published in March 2017. Kate runs writing workshops and undertakes commissions and residencies.

@kateinnes2