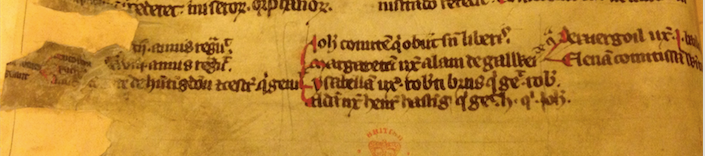

[Fol 12v of London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius E I. My photograph.]

Genealogy was fundamental to the medieval imagination, and at the heart of medieval historical writing. Chronicles, as well as romances and hagiography, are based on structures of legacy and succession, and on the genealogical concept that stories from the past justify or contest the present and make claims to the future. However, medieval genealogies are infamously male-orientated. The very notion that women possessed power and narratives capable of being communicated to future generations sits particularly uncomfortably in patrilineal narratives that often depict women as vessels for male bloodlines.

Yet it seems reasonable to assume that medieval readers, writers, and patrons, both female and male, were interested in textual representations of female genealogy and in reading about women as active agents in a temporal landscape of past, present and future. We know that historically many medieval women were influential and politically-engaged holders of land and lineage. Women also shaped and produced medieval literary culture, as readers, writers and patrons.

Perhaps the question to ask, then, is not why do so few female-orientated genealogical narratives exist, but where do they exist and in what forms? If we aren’t finding them, are we looking in the right places? This question is at the heart of my project – my doctoral thesis, creeping towards a book – on female genealogies in the medieval literary imagination. The project explores how texts from historically-motivated literary genres, such as hagiography, romance and vernacular chronicles, self-consciously depict the ways female characters’ legacies are carried and communicated through time.

The twelfth-century Life of Saint Margaret of Scotland involves various forms of female genealogy, both in its context of production and within its text. It is a biography, commissioned by Queen Edith/Matilda about her mother, Margaret, queen of Scotland. At the Women’s Literary Culture & the Medieval Canon conference in Bergen last month, I talked about how images of books within the text suggest the transmission of regnal, political and spiritual power between mother and daughter.

Clearly at least some late medieval readers, or copyists, of the Life also felt it was a text that justified and authorized female genealogy. The mid-fourteenth-century manuscript London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius E I, contains a short version of Margaret’s Life, as part of John of Tynemouth’s Sanctilogium Angliae, Walliae, Scotiae et Hiberniae. In margins below the Life lies a carefully drawn woman-orientated genealogical tree diagram. I hope to study the manuscript more fully in the coming months, but offer some early observations.

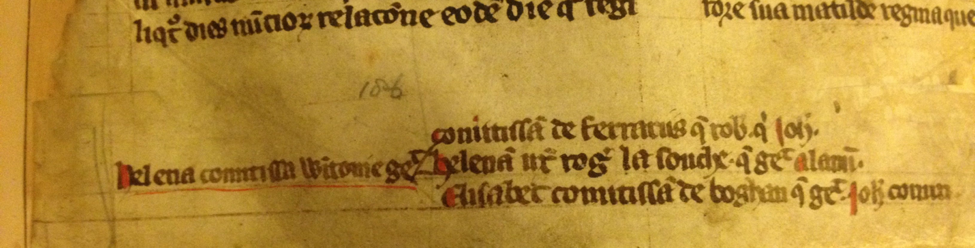

[Fols 12v and 13r of London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius E I. My photographs. The images above show the two final pages, but the whole diagram stretches over four pages (11v to 13r) and the Life occupies fols 11v to 13v.]

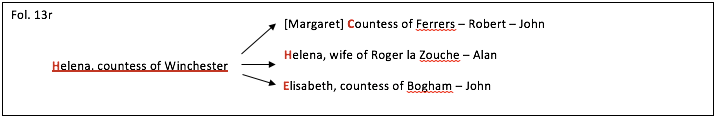

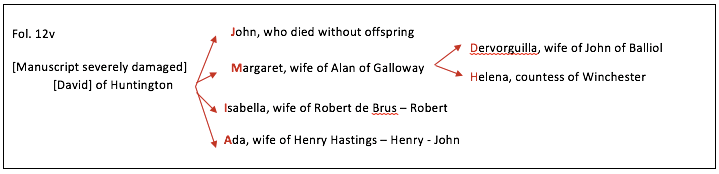

Existing descriptions of the manuscript indicate simply that a diagram of Margaret’s descendants lies in the Life’s margins. This in itself isn’t so surprising as Margaret and Matilda appear with their own rondels in a number of royal genealogical rolls in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, such as London, British Library, Royal 14 B VI. But the specific nature of this diagram is more unusual. From Margaret of Scotland, with whom it starts, to the final descendants of Helena of Winchester’s daughters, it portrays a lineage defined by women that spans three centuries. From Margaret of Galloway on folio 12v, the branches of the diagram depict three generations in which the lineage is carried exclusively by women.

[Loose and selective translation of fols 12v and 13r, in the photos above.]

The diagram focuses on powerful women who held and transmitted important lands and titles along the Anglo-Scottish border during the Scottish Wars of Independence (though it contains numerous historical inaccuracies, as is common in genealogies in chronicle and historiography). Several of the women are also known literary patrons. My interest here, however, is less the historical narrative or figures, but how the diagram authorizes a narrative of women’s political and spiritual power across time. This is not simply a record of important female heirs jotted in a spare margin.

The text is carefully written and rubricated, and appears to be in the same hand as the main text. The dates of the manuscript and people in the genealogy suggest a version of the diagram may have been part of the scribe’s exemplar. But it also seems that the scribe, who may have been John of Tynemouth himself, thought the diagram important enough to continue grafting onto in his own copy of Margaret Life. The only other genealogical diagram in this huge codex of 156 vitae is of Saint Oswin, who had a more explicit connection to John as Tynemouth priory’s patron saint. So it seems that this version of Margaret’s lineage was at least as important to John as Oswin’s, and was deliberately included.

Helena of Winchester is the unmistakable climax of the diagram. Her name is given on each of the two pages reproduced above. In the second instance it is distinguished as the only underlined name anywhere over the four pages of the diagram. Her husband, despite being politically influential, is absent. (On a side note, I love that to discover his name I had to search for “Helena of Winchester’s husband,” rather than my usual search of “[important man’s] wife.”) It is Helena who “genuit” (“bore”) three daughters: the countess de Ferrers; Helena, wife of Roger la Zouche; and Elisabeth, countess of Bogham. The husbands of the Countess de Ferrers and Elisabeth, also important men, are also absent. The Countess and Elisabeth are singularly attributed with bearing the lineages of sons that stretch out in front of them. Between the missing husbands of Helena, the Countess and Elisabeth, the diagram presents two matrilineal branches that extend for two generations before a male name is given.

This bold and unusually explicit narrative of female genealogy in the Tiberius manuscript is marginal, in the most literal sense. But it is marginal to the Life of a renowned queen and saint, who was crucial to both English and Scottish royal lines and had been canonized in the mid-thirteenth century. Margaret’s Life presides over this female genealogy and provides it with an authority that surmounts patrilineage.

What might the placement of this genealogical diagram suggest about the location of female genealogies in medieval literature more generally? What strikes me is the number of unregulated, or less regulated, and unexpected spaces this genealogy takes advantage of. It uses the infamously uncanny space of the manuscript margin. It sneaks a narrative of distinctively secular female power into a decisively religious book.

But these spaces on the edge or between, also characterize the political genealogies of Helena of Winchester and her female descendants. They themselves came to the genealogical fore as land and title holders in a contested region, the Anglo-Scottish border, at a time between, when male heirs had been lacking but anticipated for generations. Perhaps it is not surprising then that women’s genealogies, less regulated and less instituted than men’s, locate themselves in flexible and innovative (though still authoritative) literary and codicological settings.

Dr Emma O’Loughlin Bérat