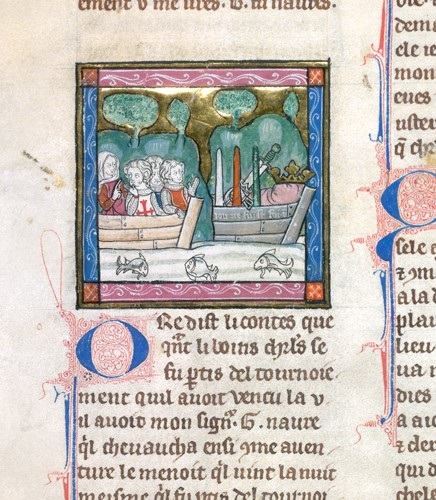

Royal 14 E III f. 125v. Source: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=54938

Within the landscape of medieval literature, Old French Arthurian romance provides a rich cast of women as subjects. The works of Chrétien de Troyes give us Guinevere, Enide, Fenice, Laudine, and Lunete. These are characters with developed personalities who frequently drive the plot of the romances in which they appear. Women as literary subjects continued to play a significant role in the prose romances of the thirteenth-century and beyond. In the Vulgate Cycle (also known as the Lancelot-Grail Cycle), women occupy narrative space and do so boldly; they are not mere ciphers to be pursued and possessed with little discernible impact on the fictional societies that they inhabit.

This wealth of female characters notwithstanding, I want to turn to a text which seems, at first glance, ill-suited for inclusion in a blog post about women’s literary culture. The thirteenth-century Queste del Saint Graal (Quest of the Holy Grail) features fewer prominent female characters compared to the rest of the Vulgate Cycle. Nevertheless, I was first drawn to explore the role of women in the spaces of the Grail Quest because the text approaches their presence and absence in ways that I find particularly interesting.

In the first pages of the Queste, a message from a hermit named Nascien is delivered to the court of King Arthur, bringing news of the Holy Grail and setting in motion the quest. Nascien explicitly prohibits women from accompanying their husbands and lovers on the quest, to the consternation and surprise of the court. He provides an ideological rationale: any knight who permits a lady to accompany him on the quest will fall into mortal sin. We are reminded that this quest is different from all those which have come before: ‘…ceste Queste n’es mie queste de terriennes choses’ (‘this Quest is not a quest for earthly things’, Queste, p. 19). The adventure is reserved for the spiritually worthy and knights who cannot renounce their earthly desires are doomed to fail the quest.

The spatial construction of the Grail society arguably seeks to replicate the kind of single-gender system that we find in medieval religious orders but it fails to do so entirely. The perfect Grail knight should be celibate in thought and action, and place his devotion to God above his allegiance to any earthly lord or lady. The reason why Lancelot, hitherto the greatest knight in the world, cannot achieve the Grail is due to his adulterous love for Queen Guinevere. Women are presented from the start of the text as the greatest barrier to success, imperilling a knight’s soul with their very presence according to the new order of spiritual chivalry.

Despite the best intentions of hermits and holy men, women do not disappear from the story altogether but at first glance it can be difficult to identify a space for them in what is, superficially at least, a male-dominated narrative. They are often relegated to extreme subject positions: angelic oracle or demonic temptress tasked with luring the Grail knights to their doom. This is not to say, however, that women play little or no part in the Queste.

I think that the complexity of the role of women is best demonstrated in the episodes involving Perceval’s Sister. It is striking to note that she is known only in relation to her famous brother and is never accorded her own name, yet she plays a vital role in the romance. She first enters the narrative by arriving unannounced at the lodgings of Galahad, Bohort and Perceval. She informs Galahad that if he follows her, she will show him the greatest adventure in the world, and accompanies the Grail knights on the next stage of their journey. In a ceremonial yet intimate gesture, she arms Galahad with a special sword girded with a belt made from her own hair.

Their interactions here are reminiscent of Lancelot’s arming at the hands of Guinevere, but with one crucial exception: the relationship is entirely chaste. Although there are some parallels between the relationship of Galahad and Perceval’s Sister to that of Lancelot and Guinevere, Perceval’s Sister is in many ways a female version of Galahad rather than a potential lover. Indeed, she and Galahad are the only two characters to be described as entirely chaste not only in deed but also in thought, meeting the Queste’s exacting new definition of virginity. In cutting off her hair to make Galahad’s sword belt, Perceval’s Sister undergoes her own ritual in parallel to the dubbing of Galahad, as if she too were becoming a Grail knight.

Another indicator which casts Perceval’s Sister in the mould of a knight is the service she renders to those in need. Along with her companions, she arrives at the castle of a woman with leprosy, whose guards force every passing virgin to fill a dish with her blood in the belief that this will heal her. Here, the female body is depicted as a vessel that can both cure and destroy, embodied by Perceval’s Sister and the chatelaine. Perceval’s sister willingly agrees to the gruesome demand, even though the Grail knights do not want her to go through with the ordeal. They are ready to take up arms in her defence but Perceval’s Sister is more than willing to sacrifice herself to cure the chatelaine’s leprosy, and to save her companions from fighting a battle with the odds stacked against them.

Perceval’s Sister allows so much blood to be drained from her arm that she expires. She dies a martyr’s death, but there is a further twist to this tale. A great storm subsequently ravages the castle and destroys it, killing everyone including the recently healed chatelaine. The death of Perceval’s Sister is therefore in vain, and brings into question the purpose not only of the act of sacrifice but of Perceval’s Sister herself and the role she plays in the Queste.

As numerous scholars before me have demonstrated (see Peggy McCracken, Susan Aronstein, and Janina P. Traxler among others), Perceval’s Sister disturbs the theological and chivalric framework of the Queste narrative to the extent that she has to be removed. So why, we might ask ourselves, is her character present in the first place? Her role is neither to act as Galahad’s lover nor to be a heroine in her own right. She is instead relegated to a martyrdom subplot through which the virgin can be exalted and sanctified, neutralising the threat of female sexuality.

The character of Perceval’s Sister exposes the misogynistic hypocrisy of Grail ideology. She would make an ideal Grail knight. She is inexplicably knowledgeable about the Grail lore (to a greater extent than any male knight including Galahad) and perfectly at ease in the landscape of the Grail Quest. There is every reason to argue that Perceval’s Sister should be able access the mysteries of the Grail; she possesses identical qualities to Galahad with the exception that she is a woman. The narrator places her death in her own hands by having her relinquish her life freely in the giving of her blood. The Grail space itself cannot be the death of her as it is for so many failed knights; unlike them, she quite clearly belongs there, but the ideological demands of the narrative cannot allow her to remain. Ultimately, her goodness proves just as troubling to the Grail Quest as the femmes fatales who also populate the romance.

I suggested in my PhD thesis that the construction of space in the Vulgate Cycle hinges on a process of emplacement and displacement. Each subject is put in their place, but from that initial place they may find stability or be displaced and relocated elsewhere. This kind of system always has the potential to create space for social transgression and resistance, which is highlighted in the example of Perceval’s Sister. Her presence refutes the notion that women are unworthy of accessing the mysteries of the Grail. Her story raises confronting questions about spirituality, sexuality, and chivalry, and in so doing places a woman at the heart of the narrative albeit for a short time. Once evoked, the spectre of women can never be erased. The women of the Grail Quest are both present and absent, at all times and in all places. Whenever I reread the Queste del Saint Graal, it is this unsettling duality which lingers longest in my mind.

Dr Leona Archer

University of Surrey