by Kate Innes

© Kate Innes

I take the flax, I take the wool

and from the distaff, thread I pull.

I take the yarn, I weave a cloth

made of many lover’s knots.

Around the spindle, I am bound.

My heart, around your heart, is curled.

Like the shuttle, up and down,

like the needle, in and out,

I will seek you till you’re found,

through all the winding world.

In 2017 I contributed two posts to this blog in which I explained the influences of hagiography and Arthurian legend on my first novel – The Errant Hours. The posts can be accessed here and here. Earlier this year the sequel was published, and I am delighted to have been asked to contribute another post about my new medieval novel.

All the Winding World is set in 1294-5 during the Anglo-French War. The youthful and reckless heroine of the first book, Illesa Arrowsmith, is now Lady Burnel, a mother and the chatelaine of a manor. But her home in the Welsh Marches is far from the peaceful backwater it seems today.

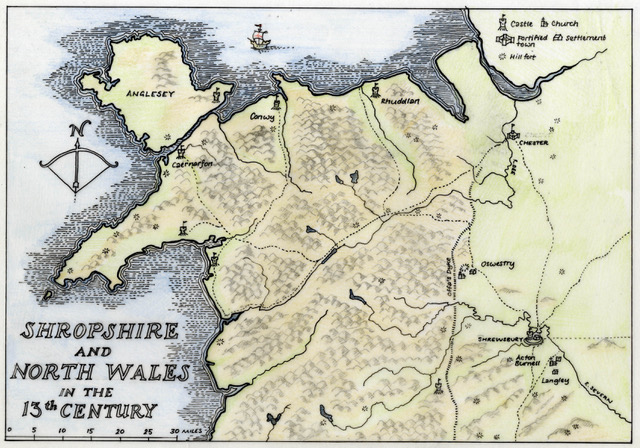

Map from All the Winding World © Kate Innes

The Marcher Lords vie against each other and against the King. The Welsh rebel against the heavy rule of the English and the English retaliate. And then, to add to it all, an avoidable and expensive war erupts with France over King Edward’s Duchy of Aquitaine. Men-at-arms brutally conscript soldiers along the Welsh border. Their cruelty instigates another Welsh revolt and this divides the available men to fight. It is, in short, a mess.

In the midst of it all, women are expected to carry on with farming, feeding, washing, shearing, carding, spinning, weaving, sewing and doing all the things that keep people alive and warm.

I was intrigued, as have been countless writers before me, by the varying experiences and expectations of men and women in a time of war, particularly as explored in the story of Penelope and Odysseus. In medieval Britain, they did not have access to Homer and other Greek versions of these tales, only to Roman interpretations. The accounts by the probably apocryphal ‘Dictys and Dares’ were the most influential. And from these sources, many medieval writers spun gold out of straw. For example Benoît de Sainte-Maure, a 12th century Norman writer, had a bestseller with his ‘Le Roman de Troie’. Recently translated into English by Glyn S Burgess and Douglas Kelly, this long and anachronistic version of the Trojan War and its aftermath, although rather wordy, has some fascinating insights into medieval ideas about warfare.

However, it is the women of the Trojan tragedy and how they were interpreted for medieval society that particularly interested me. Leaving aside the goddesses (who seem to operate in the story in a similar way to saints in medieval literature) there are two principal and opposing active female icons – Helen and Penelope.

Helen, filled with lust, abandons her duty, gives into temptation and runs off with the buff but rather stupid Paris, leading to widespread death and destruction (perhaps a signifier of Eve avant la lettre for the medieval audience). Penelope on the other hand is the ideal of a good wife. She stays faithful. She stays at home. She stays loving. She shows her wisdom in resisting the suitors but is never violent. She weaves and unweaves, being deceitful through a most suitable female activity.

As a child, I adored the Greek Myths and the tales of the Trojan War, but now that I’m a woman, I look at them in a rather different way. Specifically, I’ve had enough of the passive, weeping woman waiting at home. For a writer, things become quite a bit more interesting when expectations are shaken up. For example, in All the Winding World, I wondered what would happen if Penelope, the faithful wife, lost her patience and went off and rescued Odysseus herself? If she had, I very much doubt it would have taken her ten years to get him home.

All the way through the book I was interested in the symbolism of spinning, weaving and knotting that was an important part of women’s work, but also could represent their cunning. Knot magic was a potent idea at the time. It was understood that demons and other evil spirits could only travel in straight lines, so making an endless knot (like Solomon’s Seal or Solomon’s Knot) became a powerful apotropaic charm, whether made in thread or scratched on the walls and door jambs of churches.

Circe – a dangerous magical woman – was said to have taught Odysseus an intricately made ‘cunning knot’, to prevent robbery of his possessions. Circe had an ‘immortal loom, an enchanting web,’ and was also described as ‘the nymph with glossy braids’. Women’s hair, long considered to be a man’s downfall, had to be constrained to make it safe, by being plaited, braided, knotted and controlled. It is clear that working with threads of wool/silk/hair, although a safe and appropriate feminine task, was also perceived as a source of power that could potentially lead to male destruction.

The wheel on the front cover of All the Winding World, turned by Lady Fortune (Ms 1044 Fol. 74 Bibliothèque Municipale, Rouen), looks very much like a spinning wheel with the woman in a position of power right at its centre and men rising and falling at her will. An image heavy with numerous layers of symbolism.

The Wheel of Fortune Ms 1044 Fol.74, 14th century, French School, Bibliotèque Municipale, Rouen, France/Bridgeman Images. Detail from cover of All the Winding World – © Kate Innes.

But the power of fabric manipulation was also brought beautifully into reality through the marvelous, almost miraculous, work achieved by the medieval English embroiderers. Opus Anglicanum (English Work) was another major influence on the plot of All the Winding World. Thanks to an exhibition at the V&A Museum in London in 2016, I was able to see at first hand the extraordinary detail of these garments. Made with silk and gold thread on fabric imported from the Far East and often studded with pearls and jewels, taking hundreds of hours of stitching, the vestments and garments of English Work were traded as diplomatic gifts amongst the upper echelons of the clergy and nobility. It was often women who worked on the garments, but rarely women who saw the profit of it.

One of the most amazing vestments in the exhibition was the Madrid Cope (https://www.trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/individual-textiles-and-textile-types/religious-vestments-and-other-textiles/daroca-cope a large ceremonial ecclesiastical cape). On it is depicted the first few chapters of Genesis, including the Creation of the beasts and of mankind, the Temptation, the Fall and the Expulsion from Paradise. At the base of the garment is the symbolic image of God’s curse on Adam and Eve. They are depicted naked. Eve is spinning – to make clothes now that they had lost their innocence, and Adam is delving – digging to plant vegetables now that they were going to become farmers and not hunter/gatherers around the Garden of Eden.

There is so much to explore in this idea (the whole of the development of civilization for a start), but I am particularly interested in the image of Eve with her distaff and spindle, starting that long and twisted journey to the love/hate relationship many women now have with clothes and the judgments they evoke.

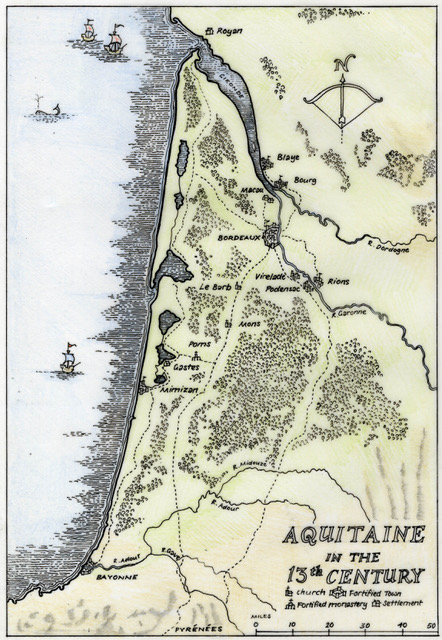

Map of Southwest France from All the Winding World © Kate Innes

One more thread (if you will allow me!): half of All the Winding World takes place in Aquitaine, around Bordeaux and on the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostella that wend through southwest France. This area was part of Occitania, a distinct cultural and language area in which women were given a little more creative power and personal autonomy than in Northern Europe. In this environment the concept of courtly love was created and flourished in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, and women, known as trobairitz, were composing and singing courtly poems alongside men. In my story Azalais of Dax is a trobairitz and also Illesa’s cousin. This character is influenced by the female poet and singer Azalais de Porcairagues who lived in Provence in the mid-twelfth century.

Azalaïs de Porcairagues in Bibliothèque Nationale MS cod. fr. 12473. By 13th century artist [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

She sings several songs from a collection of 13th century French polyphony, the Codex de Montpellier, and also the ‘song’ at the top of this post, written for her by me. Her skills are crucial to the plot, and her confidence and freedom is a breath of fresh air in the stifling misogyny of the time.

*********

Kate Innes was once an archaeologist, teacher and museum education officer. She now enjoys living in the past by writing historical fiction. Her first novel, The Errant Hours is a Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choice and was included on the Medieval Women’s Fiction reading list at Bangor University. Her poetry collection Flocks of Words was shortlisted for the International Rubery Award. Kate performs her poetry with the acoustic band Whalebone and runs creative writing workshops.

All the Winding World is available as a paperback or ebook from Amazon and to order from most bookshops.