by Shazia Jagot, University of York

In the series finale of the American sitcom, The Good Place, the redeemed demon, Michael (played by the effortless Ted Danson) reels off a list of historic personages newly admitted to the paradisial afterlife: Roberto Clemente, Zora Neale Hurston, St Thomas Aquinas, Hazrat Bibi Rabia Basri, Clara Peller. The mention of Hurston and Aquinas alone made my heart flutter, but it was the mention of ‘the eighth century Sufi mystic poet […] Hazrat Bibi Rabia Basri’ that made it soar.

Rabi’a has occupied my mind since I decided to speak about her at the conference Speaking Internationally: Women’s Literary Culture and the Canon in the Global Middle Ages. With Rabi’a, I was able to bring medieval Muslim mystics into critical conversation with work on Western European female mysticism and just like in The Good Place, I had the pleasure of introducing Rabi’a to a new audience.

In the minute yet mighty introduction that Michael delivers in the philosophical comedy, ‘Hazrat Bibi Rabia Basri’ is prefaced with an explanation to ensure audiences understand the reason for including her in the notable list; Rabi’a is, as Michael notes, ‘the eighth century Sufi mystic poet’. Rabia Basri (Arabic, Rabi’a al-Basriyya also known as Rabi’a al-Adawiyya) is an eighth-century mystic, or to be more precise an ascetic, who occupies a significant position in the religious and cultural orbit of Muslims across the globe.

Indeed, the particular expression of her name in The Good Place suggests that one diligent writer discovered Rabi’a in a Persianate context signalled in ‘Hazrat Bibi’. Here, we have a double whammy of reverential titles that signals her exceptionalism among the faithful: ‘hazrat’, the honorific title used to designate respect to religious and learned people (hazrat is the Persianized hadh’rat from Arabic), and ‘Bibi’ a Persian term that denotes respect and endearment for women that found its way into Urdu, Hindi and a number of South Asian vernaculars. ‘Hazrat Bibi Rabia Basri’ commands respect; her praises continue to be sung as one of the first female Sufi poets whose voice, and actions exemplify not only her deep devotion to God, but the independence a virtuous, learned Muslim woman could hold in the early Islamic period.

However, unlike a number of medieval Muslim women, we know very little about the life of the historic figure Rabi’a al-Adawiyya. In fact, as Rkia Elarouia Cornell so assiduously remarks, ‘everything we know about her has been constructed’ (p. 7). The few facts we have about the historic Rabi’a suggest she was a native of Basra (present-day Iraq) where she lived between c. 717 and 801, and where some claim she is buried. It is possible that she belonged to ‘Adi ibn Qays, an Arab clan that belonged to the wider tribe of the Prophet Muhammad but later narratives also suggest she was an orphan and a non-Muslim slave. Untangling this construction, as Cornell has done in her magisterial study, is a complex yet fascinating process and takes us across texts and time as the development of Rabi’a’s narrative stretches from the ninth-century right to the present-day.

The earliest written references to Rabi’a appear in the ninth-century where she is noted for her exceptional piety, her asceticism, and her celibacy: practices that singled her out as a pious Muslim, an early zuhhad (renunciant) of the faith. From this point onwards, Rabi’a’s narrative begins to evolve taking form almost exclusively in literary and poetic spaces where Rabi’a as the first female Sufi poet is born despite a complete absence of evidence: there are no extant poems, anecdotes or biographical notes composed by the historic Rabi’a. Moreover, she lived at a time when both the nomenclature and doctrine of Sufism was not only in its nascent years, but malleable and loose – few of the early renunciants, including Rabi’a, were called Sufis in their own lifetimes.

Nonetheless, Rabi’a is associated with two of the most well known tropes of Sufi poetry: the notion of God as the Divine Beloved, and the mystical union between God and the Sufi as a form of divine love, rooted in the Qur’anic verse: ‘God the Exalted has said: “Say, if you love God, then follow me, and God will love you” (al-Imran, 3:31). Rabi’a is celebrated as the earliest poet to extol her love for the divine, best encapsulated in the ‘Poem of Two Loves’:

I love You a double love: I love You for Yourself

Loving You passionately has put me off others.

I love You for Yourself so You would drop Your Shutters to let me see You

I am not the one to be thanked, all thanks must go to You [trans. Abdullah al-Udhari p.104]

Not only does this denote Rabi’a’s deep devotion to God, but reinforces her celibacy, a practice not imposed upon either early pious renunciants or later Sufis.

Countless anecdotes narrate Rabi’a’s refusal to marry despite frequent proposals especially from eligible men, including Hasan al-Basri (c. 642 – 728) another leading early pious Muslim and another notable anachronism in Rabi’a’s narrative, and her interactions with male interlocuters where she dispenses wisdom in acerbic tones with the authority of a learned teacher and a woman who does not suffer fools gladly.

What’s fascinating here is to see a Muslim woman capturing the imagination of male polymaths, Sufi and non-Sufi alike, who create and reshape a multivalent voice that holds as much, if not more, authority than her male counterparts. It is the very same male writers who are also responsible for establishing Rabi’a’s vita, first set down in the early thirteenth-century by the Persian metaphysical poet, Farid al-Attar (c. 1140s – 1221).

Attar is the first to construct Rabi’a’s vita in his hagiographical prose work the Tadhkhirat al-awliya (‘Memorials of the Saints’), a text that contains 72 biographical entries of individuals celebrated for their piety only one of which is dedicated to a woman. In the Tadhkirat al-awliya, Attar constructs Rabi’a’s vita using commonplace tropes found in the writing of hagiography: she comes from humble, poor beginnings, so Attar tells us that Rabi’a was an orphan, and a non-Muslim slave. A miraculous event occurs at the time of her birth which includes a Prophetic intercession. Rabi’a’s auspicious beginning is short-lived. Her family die in a famine; she is then abducted and sold for 6 dirhams.

It is her time in servitude that propels her into a life of mysticism, relayed by Attar with particular dramatic flair. After being accosted by a stranger, Rabi’a flees and injures herself:

“Lord God,” she cried, bowing her face to the ground, “I am a stranger, orphaned of mother and father, a helpless prisoner fallen into captivity, my hand broken. Yet for all this I do not grieve; all I need is Thy good pleasure, to know whether Thou art well-pleased or no.”

“Do not grieve,” she heard a voice say. “Tomorrow a station shall be thine such that the cherubim in heaven will envy thee.” “Do not grieve,” she heard a voice say. “Tomorrow a station shall be thine such that the cherubim in heaven will envy thee.” (trans. Arberry, p. 32)

The next day, a divine light (nur) surrounds her head filling the room, a light witnessed by her master who upon recognition of her status as an awliya (‘friend of God’) promptly releases her from his service: ‘“Give me permission to depart,” Rabi’a said’ (Arberry, p. 32)

Despite my use of Arberry’s rather parochial translation here, Attar’s hyperbolic vita is riveting; Rabi’a’s poverty, her life as a commodity, her exceptionalism, are all common enough tropes in hagiography but are relayed with dramatic and creative potency.

Attar’s final notes on Rabi’a reveal that she spends the rest of life in devotion to God, but he also recounts a life well-lived: Rabi’a is lively and sociable, she interacts with both men and women and is always mindful of her deep devotion to God.

Attar’s entry on Rabi’a has garnered critical attention outside of Arabic studies through the work of Margaret Smith, called the ‘English Attar’ (Cornell, p. 18) in light of her pioneering work on the Muslim mystic. In 1928, Smith, ‘a sometime scholar of Girton College, Cambridge’, published the first full critical biography of Rabi’a based on Attar’s biographical note drawn from her doctoral work undertaken at University College, London. Smith’s rigorous study, informed by her training in Arabic and Persian philology, set the foundations for critical scholarship on the female saint and continues to remain the most influential and widely-read study on Rabi’a across languages.

Smith’s work was revolutionary in so many ways, not least in her efforts to to dispel the orientalist myths of Muslim women: an effort not lost on our present-day. In her opening remarks she foregrounds the idea of complete and equal parity between men and women in the development of Islamic mysticism:

‘In the history of Islam, the woman saint made her appearance at a very early period, and in the evolution of the cult of saints by Muslims, the dignity of saintship was conferred on women as much as on men. As far as rank among the ‘friends of God’ [‘awliya], was concerned, there was complete equality between the sexes.’ (p. 1)

The implications of this have been explored most fully by Claudia Yaghoobi who argues that Attar’s Rabi’a challenges the gender norms of the day (pp. 45-6). I’m intrigued however by the role of early twentieth-century Orientalist scholarship here. In Margaret Smith we find an Englishwoman bringing to life a Muslim female mystic through the literature of a Persian male poet.

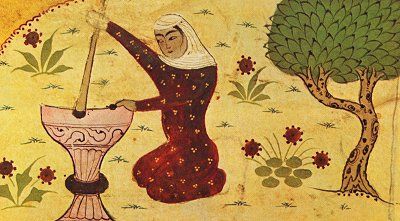

So many fascinating connections can be drawn out from this alone that takes us across England and the Islamic world, both medieval and modern, and across male and female voices, thinking too about form, and modes of writing. Fascinating still is that these connections can be brought right to the present-day expressed in the visual footnote to ‘Hazrat Bibi Rabia Basri’ – but, blink and you’ll miss Michael’s reference to the most renowned female Muslim mystic in the Islamic world.

I’ve compiled a short bibliography if you’re interested in learning more about Rabi’a al-Adawiyya and/or medieval Muslim women:

Nabia Abbott, Aishah the Beloved of Muhammad (University of Chicago Press, 1942) and The Two Queens of Baghdad (University of Chicago Press, 1946).

Leila Ahmed, Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate (Yale University Press, 1992).

Rkia Elarouia Cornell, Rabi’a From Narrative to Myth: The Many Faces of Islam’s Most Famous Woman Saint (Oneworld, 2019).

Maria M Dakake, “Guest of the Inmost Heart”: Conceptions of the Divine Beloved in Early Sufi Women”, Journal of Comparative Islamic Studies 3 (2007).

Asma Sayeed, Women and the Transmission of Religious Knowledge in Islam (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Annemarie Schimmel, Mystical Dimensions of Islam (University of North Carolina Press, 1975).

Laury Silvers, “God Loves Me”: The Theological Content and Context of Early Pious and Sufi Women’s Sayings on Love’, Journal of Islamic Studies 30 (2010).

Margaret Smith, Rabi’a the Mystic and her Fellow Saints in Islam (Cambridge, 1928).