by Ruth Wiggins

When I am gone / will my successor / some sister / of the future / lift my books to her face / and find me / in them (Ruth Wiggins, ‘Dolls of lead’)

I would describe myself as a walking poet. By this I mean that many of my poems have either grown directly out of spaces I’ve walked through or have instead begun elsewhere then taken shape under the influence of the rhythm of walking. When I first started work on the poems that would later become The Lost Book of Barkynge (a conjectural history of Barking Abbey) I was engaged on a project directly related to terrain and to a sense of place. Specifically, the course of the river on whose banks Barking Abbey once stood: the River Roding. Wanting to write about the Roding, I worked my way south from its source, but when I reached Barking my encounter with the abbey ruins stopped my journey in its tracks, as the muffled voices of history crowded in. Thinking at first that I might include the medieval abbey as just another part of my river sequence, I became increasingly distracted by the weight of untold history. The abbey green began to reveal itself as a geopsychic space, with the nuns of Barking as its genii loci. At this point an encounter with Diane Watt’s essay ‘Lost Books: Abbess Hildelith and the Literary Culture of Barking Abbey‘ helped give early shape to my sense of the abbey as not only a place of devotion but as a place of learning. A home for the bookish…

Map-drawing is also a part of my writing process and for the river project I had drawn lengths of its course, focusing on the churches that dot its banks. This process took on more significance for me as the abbey grew in my mind as a culmination of sites, with the river acting almost as a sacred watercourse. The symbolic language of maps has something in common with poetry, the way they can both conjure the contours of things, but also the human interconnectedness around them. We use the word legend for the key that deciphers all those cartographic squiggles (I have always liked the way a church-with-a-steeple echoes the glyph we use to denote the female) but the word legend also conjures extraordinary or miraculous events in the dim and distant past. The early medieval was a period often viewed through the lens of miracles and visions, and the encoding of suchlike helped ensure Barking’s reputation as a site of religious significance, fit to draw pilgrims. Legend takes its meaning from the Latin legenda meaning ‘things which ought to be read’, and I became obsessed with understanding and retelling the extraordinary lives of the women of Barking in a form that had urgency, an ought-to-be-read-ness.

In the period between my discovering the ruins and the onset of the pandemic, I tried to embody their lives by visiting museums and historical buildings, to help flesh out my sense of them through encounters with artefact and location. Leper chapels; trays of archaeological finds, gold threads and writing equipment; curfew towers. But once Covid closed all our doors, and the only ones left open were virtual, I had to dive into online research instead. This was quite a different, less embodied writing process for me. I am not a historian, but fuelled by the wealth of scholarship there, I began to get a sense of the lives of the women who would have lived in and around the abbey. Accordingly, the collection comes with an extensive further reading list. Looking back at this list now, reminds me of just how maddening I found the Covid-induced impossibility of field notes, and how I had to replace my usual writing practice with what was in effect a virtual pilgrimage through the available literature: materials ranging from articles on early stained-glass windows; the role of friendship & female community in medieval England; religious discourses on blood & sweat; the link between auroras & rhetoric; plague, intercession, patronage; fishing & tidal surges in the Thames… I became mesmerised and went through a profoundly unpoetic period of wanting to shoehorn as much history and fact as I could into the poems! Until the day I realised I could instead turn the collection into more of a meta-text, of which the poems were but a part. Stripping out what I had come to regard as factual clunking in the poems, I curated a second half of the book, one including maps and timelines, and notes exploring characters and their period more fully; with the poems themselves now accompanied by lyric captions to foreground historical women and their milieu in terms of both place & time.

I became especially interested in early female literary communities and how the uniqueness of the monastical set-up meant women could perhaps for the first time escape the perils and drudgery of the domestic sphere and focus instead on their inner lives and creative responses to their faith. How intoxicating it must have been to encounter the written word for the very first time and to be immersed in a devout but bookish environment. In terms of women’s literary culture in those early days of the abbey, we know that women could write, indeed that they penned letters, medical treatises, Lives of saints…and scholarship suggests many of the anonymous texts still in existence could well have been written by women, or indeed as a collaborative, cross-community effort… In his Ecclesiastical History, Bede writes that there was a libellus or little book (now lost) telling of the mysteries and miracles that helped cement Barking’s reputation, and he waxes lyrical about some of the early figures there. Making the assumption that this little book was written in-house at Barking and thinking about the exchanges of letters and ideas in the broader religious community of the time, I chose (perhaps mischievously) to weave words found in Bede and Aldhelm into the letter-poems of their contemporary, Abbess Hildelth. This was a way of suggesting that she may have in fact influenced the work of her better-known brothers.

It is difficult to write well in a cultural vacuum, and female authorship at the time would have necessitated a community of likeminded readers and writers. Indeed, it still does. My own collection builds on the scholarship and words of others and reaches out to its own community of readers. Whilst writing these poems, the chance finding of an oyster shell on a beach, whose shape reminded me of a nun in her habit, prompted me to reflect on reefs. How oysters are gregarious and settle on older oysters in a community of shells. The fact that they switch backwards and forwards, male to female throughout their lives, seemed to me to hold an important message about community and the partial transcendence of gender that early monastic life might have offered. The idea of the oyster reef makes me reflect on the networks & strategies we can call upon, particularly as women, in our creative work: community, but also the need for solitude, a place to freely think and feel, unfettered. Although I do not share the beliefs of the sisters of Barking, I do believe in the authenticity of their lives, and I hope my poems speak to that lived experience. Imagining the fishing-smacks transporting their oysters up the sacred watercourse of the River Roding, I see Barking Abbey as a reef, one we can still lean into and grow from today.

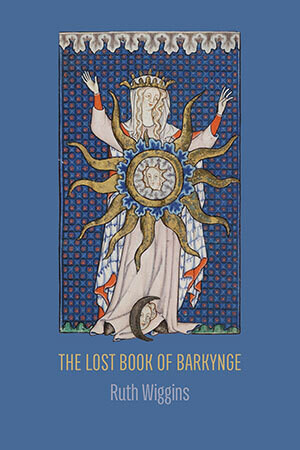

The Lost Book of Barkynge (Shearsman Books, 2023), by Ruth Wiggins, is a lyric history of Barking Abbey told in the voices of the women who lived there during the nine centuries of its existence.