By Liz Herbert McAvoy

Corbel depicting the head of a woman outside St Mark’s Chapel, Bristol (c) Liz Herbert McAvoy

The protracted meeting in Norwich between the aspiring urban vowess, Margery Kempe, and the anchoress, Julian of Norwich, in the latter’s cell at St Julian’s church, has been much discussed, not least in other contributions to this blog. There, Margery was eager to receive guidance from the older visionary to validate her visionary experiences and allay her anxieties about their provenance. In Chapter 18 of her book, Margery describes how, during their meeting, Julian, as ‘an expert in swech thyngys’ (that is to say discretio spirituum or the discernment of spirits good and bad) was able to reassure Margery that her visions were, indeed, of divine origin and that she should follow wherever they led her.

This account of the meeting of two devout women living in the same urban region in the early fifteenth century is important to our understanding of the type of religious solidarity, devotional impulses and levels of education shared by pious lay and religious women in urban environments, based in part on the rapid emergence of a new and affluent mercantile ‘middle class’ enjoying varying degrees of literacy. Julian’s advice, moreover, had a profound and lasting effect upon Margery, emboldening her to relinquish her privileged life as a wealthy merchant’s wife, daughter of an urban mayor and respected mother of fourteen children. A pivotal moment in Chapter 15 of her book recounts how, upon the birth of her fourteenth child, Margery took up the guise, clothes and devotional practices of an urban ‘vowess’: that is to say a lay woman who took a vow of chastity to live ‘the mixed life’, combining monastic-type prayer practices with an equally committed mission of care within the community. In this way, the urban vowess could simultaneously emulate both Mary and Martha of biblical lore (e.g. Luke 10: 38-42). The fact that urban vowesses were almost always widows, however, was a problem that the married Margery had frequently to negotiate – to varying degrees of success or failure, as has been well documented.

It was in the visible guise of vowess that Margery arrived in Bristol during the summer of 1417, some four years after visiting Julian. Here, so we are told in Chapters 44 and 45, she stayed for nearly eight weeks while awaiting a ship to take her on pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain. Bristol, like Norwich, was a centre of international trade within which increasingly wealthy mercantile communities lived and practised what were clearly high levels of religious devotion, pouring large proportions of their wealth into the lavish provision for, and maintenance of the city’s many parish churches. They also offered highly conspicuous support for the city’s religious orders and, at times, its recluses. The unpublished work of Stephanie Adams has demonstrated, moreover, that this was particularly true of a large proportion of wealthy urban wives and widows in the city who helped to generate and maintain what was clearly a vibrant literary and devotional culture. It was known, moreover, for its particularly lively and devout Corpus Christi celebrations, the street-party for which Margery attended during her time there, although her excessive displays of ecstatic piety during the celebrations invoked approval and disapproval in equal measures from the local women.

A small collection of late-medieval manuscripts extant in the Bristol city archives bear close links to such a female-focussed devotional culture within the city. For example, a beautifully preserved Latin Book of Hours commissioned in 1479 for or by a mayor of the town named Philip Ryngeston (BCL, MS 11) not only reveals Ryngeston’s penchant for a book of high status befitting his elevated social position, but also an aspirational Latinity on the part of an urban layman. Indeed, his commissioning and ownership of this handsome volume, replete with one entrancing head-and-shoulder image of a merchant from this wealthy community dressed in the highly fashionable garb of the day, testifies also to the misconception that Books of Hours were largely commissioned by or for women readers.

Fashionable merchant. MS 11, fol. 24v. By kind permission.

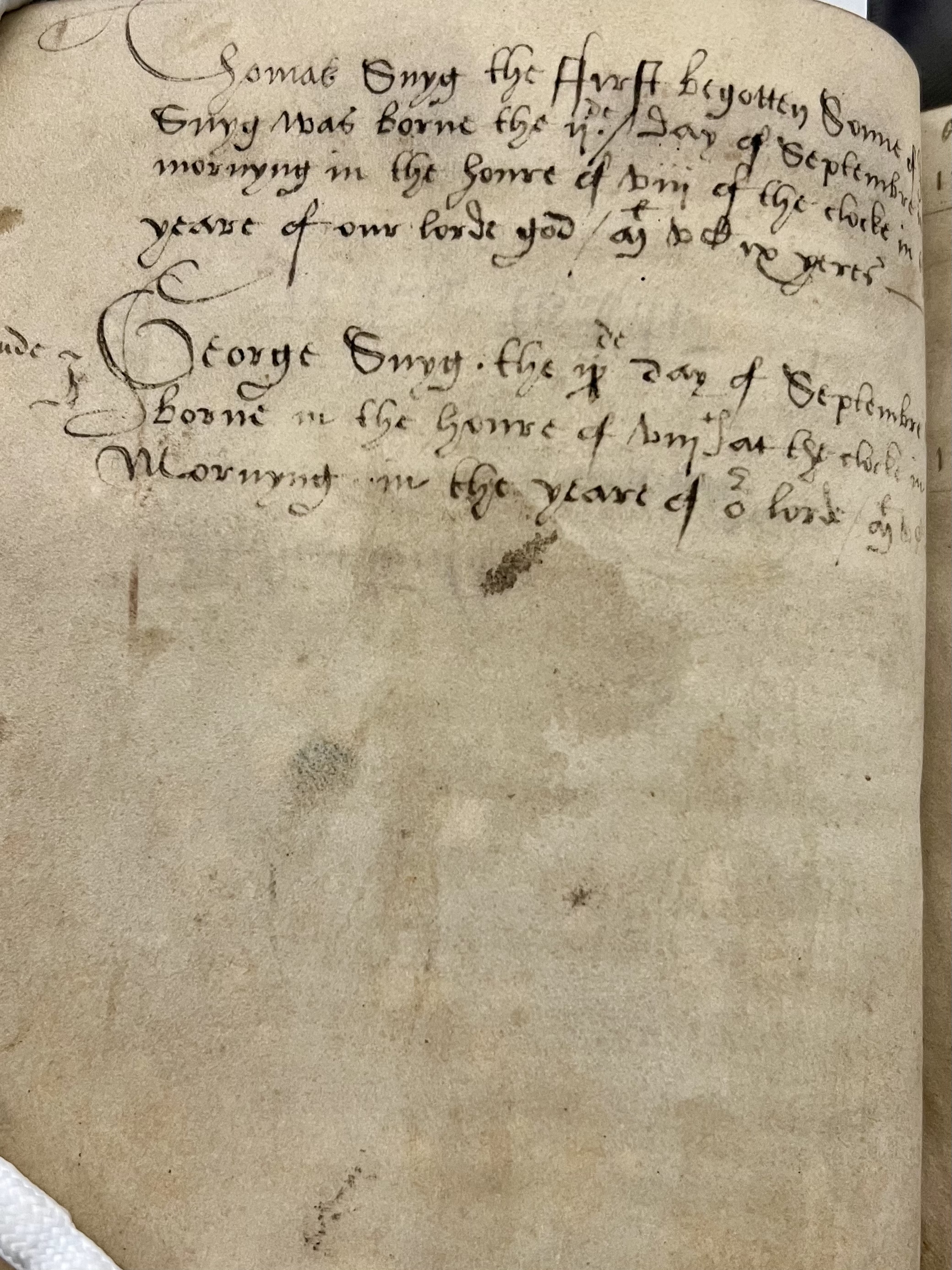

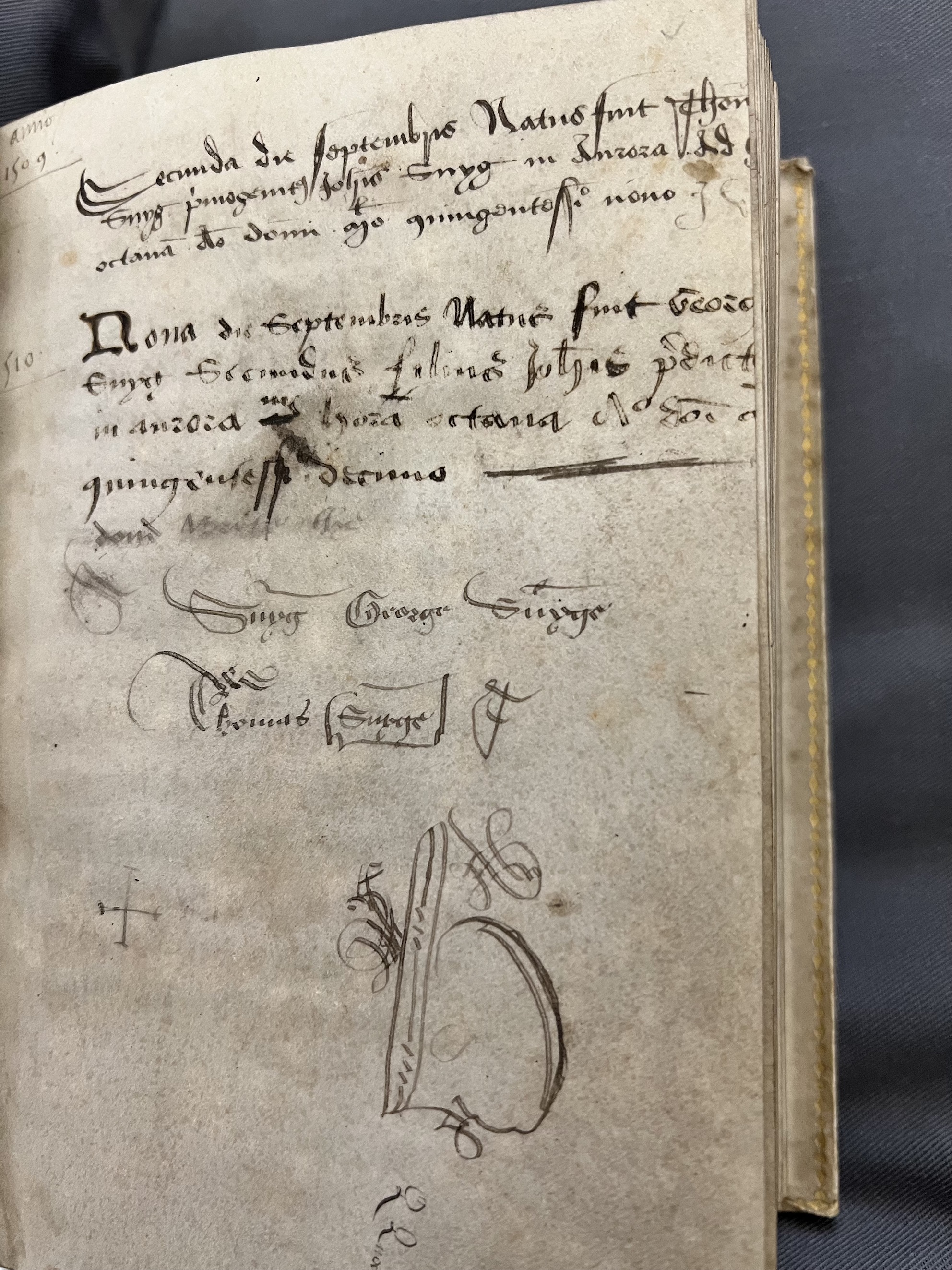

Nevertheless, we know that this decorative and expensively produced book did soon pass into female ownership because, in 1509 and 1510 respectively, Ryngeston’s daughter, Agnes, and her husband, a merchant named John Syngg, used empty folios at the front of the manuscript to record the births of two of their sons (fols ivv-vr), suggesting that Agnes had brought her father’s Book of Hours with her when she married. Moreover – most unusually in such a context – these births are recorded in both English and Latin, either by John Snygg or Agnes herself, demonstrating an aspirational latinity within this domestic mercantile scenario.

1a. Birth announcements in English MS 11, fol. 4v. By kind permission.

1b. Birth announcements in Latin. BCL, MS 11, fol. 5r. By kind permission.

The archive holds another Book of Hours (BCL, MS 14), equally elaborate, also written in Latin and dated to 1400. Known now as the Ruddock-Clyve Hours, internal evidence, including the depiction of an unknown woman flanking an image of Virgin and child alongside St Augustine, points towards female commissioning and/or ownership, most likely belonging to merchant’s wife, Isabella Ruddock-Clyve, who died in 1434 and whose will survives in the Public Record Office. The book is distinguished by the inclusion of a full-page image of the Annunciation (fol. 14v).

Annunciation. BCL MS14, fol. 14v. By kind permission.

It is also distinguished by the later addition of written entries of female interest – Mary’s Presentation at the Temple and the Visitation of Mary to Elizabeth, for example. After Isabella’s death, moreover, her daughter (or, perhaps, daughter-in-law, who was also named Isabella), deliberately consolidated the book’s female-coded credentials by inserting a memorial prayer for her mother on fols 46r-46v.

Given the fervour of Bristol’s mercantile devotion, to which these two manuscripts testify, Margery Kempe would have encountered many women like Isabella and Agnes during her eight-week stay in Bristol, especially during the Corpus Christi celebrations, mentioned above, where the town’s inhabitants ‘wonderyd up-on hir’ greatly as she ‘roryd’ in the public street and cried out that she was dying. Indeed, throughout the fifteenth century and beyond, the city’s religious landscape was dominated by extraordinarily wealthy laywomen intent on living visibly pious and devoted lives. This community of wealthy women was also particularly close-knit, enjoying strong and entangled friendships, marital alliances and pious networks; and, while their husbands often served as dignitaries in their respective parish churches or else on the municipal council or guilds, these redoubtable wives and widows often outdid the men in their performance of good works, both in terms of their church donations and bequests itemed in their sometimes very lengthy wills. No doubt, it was some of such women who invited Margery into their homes to share meals with them and to talk about things of God, as recorded in Chapter 45 of her book.

Margery Kempe, Julian of Norwich, Isabella Ruddock-Clyve, Agnes Ryngeston-Snygg and their books all bear witness to the type of devotional culture that dominated the urban landscapes of medieval England during the fifteenth century. While few women – and even fewer men – expected to be subject to the type of visionary experiences enjoyed by Margery and Julian, nevertheless, widespread evidence from wills and church records suggest that women from all social levels were deeply involved in intense devotional activities, both in terms of shared networks and in terms of material bequests and literary activities. Indeed, the Bristol records suggest that the men within this vibrant community frequently took their lead from their women and the cultures of female devotion they generated. Such piety was manifested not only in church benefaction but also generous bequests to local monastic institutions; and, in at least one case, to a local anchoress.

Scholarship of the last forty years or so has revealed to us the extent to which, in almost every part of England, the withdrawal of women into the anchoritic life had multiplied between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. It has also shown how this female dominance had a resounding influence upon the spirituality of the urban laywoman – again attested by the meeting of Margery and Julian. It has also become clear that the reading and other devotional practices enjoyed by anchoresses were emulated closely by women from the nobility and gentry. The upwardly-mobile pious mercantile women of late medieval Bristol were no exception. Like Julian’s Norwich, Bristol had its fair share of anchorites, both male and female, during the Middle Ages. A cell on the former ‘wilderness’ of Brandon Hill (now a public park), for example, had been established towards the end of the twelfth century, with an anchoress named Lucy de Newchirche having been enclosed there in 1351. Between 1314 and 1480, this same anchorhold had housed at least four anchorites, and contemporary chronicler, William Worcester, inferred in his account of the city that mariners used to climb to the hill’s summit to consult the recluse there, no doubt seeking some kind of blessing (or offering thanks) for safe passage across the sea.

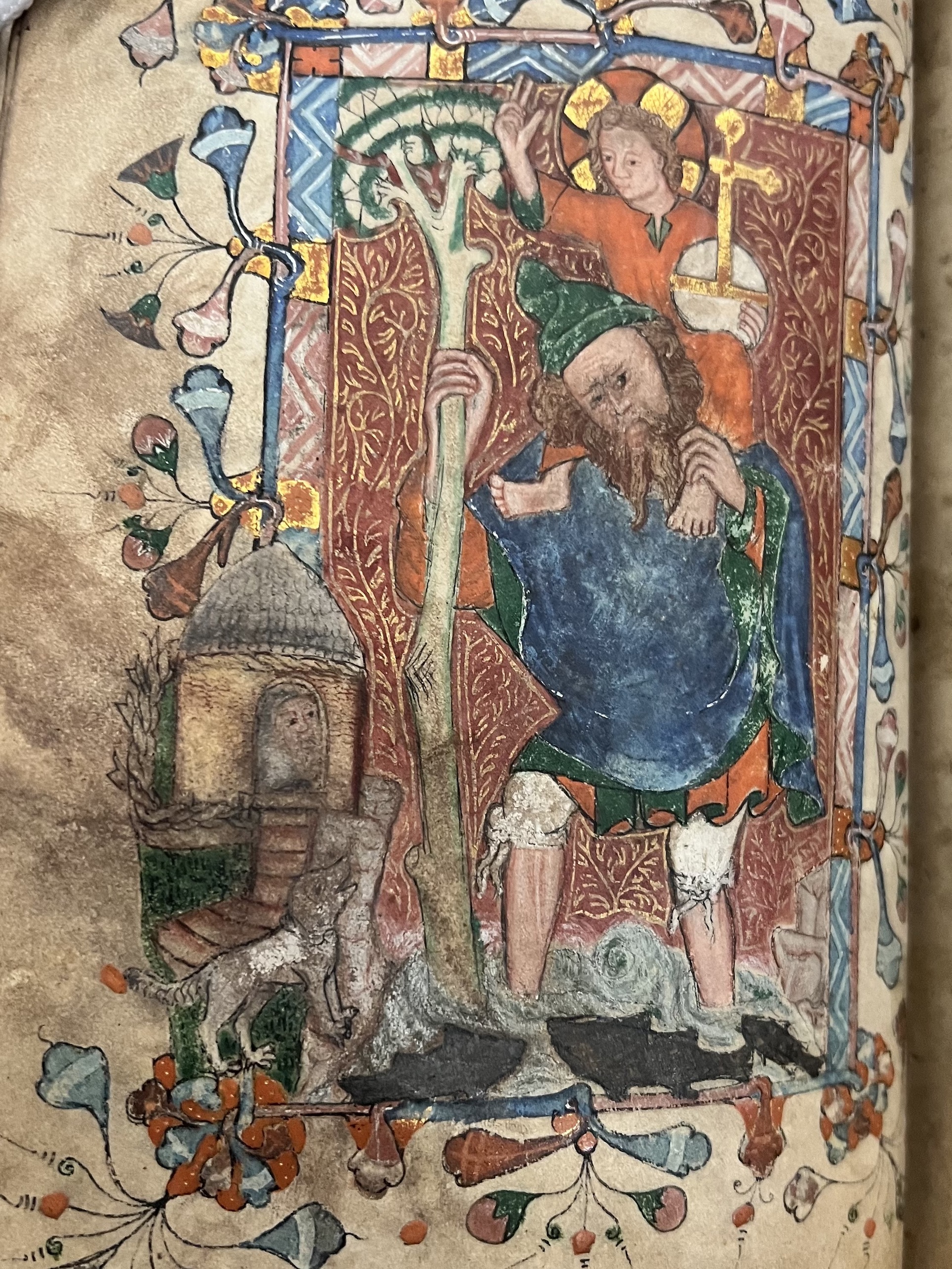

Such anchoritic activity on Brandon Hill is also testified to in another full-page image in Isabella Ruddock-Clyve’s Book of Hours. Here, on fol. 11v, is depicted an image of Saint Christopher transporting Christ across the river.

St Christopher. MS 14, fol. 11v. By kind permission.

This river is clearly the Avon as it flows past the local landmark of Ghyston Cliff, where records point towards the presence of at least two other anchorite cells. In this image, the wattle cell of the anchorite is situated at the apex of Brandon Hill high above the river and likely nods towards Saint Brendan himself, who, at least within local folklore, was deemed to have been the anchorhold’s original occupant. This may explain the inclusion in the image of a barking dog, associated with Brendan’s Vita and guarding the anchorite cell of the saint. Whatever the truth of these hagio-mythological associations, it remains true that Brandon Hill was deemed to be a holy site within the local religious landscape because of a perceived resemblance to Mount Calvary.

The prominence given to Saint Christopher in Isabella’s Book of Hours is not as unusual as it might at first seem. The saint seems to have enjoyed semi cult status in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Bristol, probably because of his role as protector of travellers (especially mariners). Indeed, the same Book of Hours also includes a Memoria of Saint Christopher (fols 11v-12v) alongside the image. These two testimonies to the saint’s popularity are further supported by the notable devotion shown to him by two other Bristol widows whose names crop up time after time in fifteenth-century records: Alice Chester and Maud Baker (also known as Maud Spicer). In 1483, for example, among many other costly donations, Alice financed the building of a new rood loft bearing an image of Saint Christopher on the north side of All Saints parish church in the city centre. Similarly, Maud, who, incidentally, became a sworn vowess upon her widowhood in 1492, commissioned a wall-painting of Saint Christopher to cover the lower part of two pillars in the same church, ‘which cost her 30s’. She also paid for the gilding of the same rood loft that Alice had originally financed, suggesting that the two women knew each other well and worked together to improve their church. Indeed, the extant benefaction list of All Saints points towards an informal library of books housed in ‘the grate at St Christopher’s foot’ in the church for public use during the same period, providing us with an indication of the country’s first public library. We know, too, that one of these books was stolen from this location sometime before 1449/50, turning up eventually in Santiago de Compostela. It is perhaps testimony to its preciousness that it was eventually brought back to Bristol and restored to All Saints’ library – but only to be stolen once more!

MS 14’s representation of St Christopher and Christ alongside a local anchorite amid a recognisably local landscape helps to account for the perceived sanctity of the city and its role as a hub for trade and travel, as well as flagging some of its devotional preferences. As the wives – and then widows – of sea-faring merchants, Alice Chester and Maud Baker, like Isabella Ruddock-Clyve, would no doubt have spent much of their lives fretting about the dangers of their husband’s and other relatives’ sea-travel, hence their very visible devotion to Saint Christopher.

In her book, Anchorites and their Patrons in Medieval England, Ann K. Warren notes other recorded anchorites in Bristol occupying cells in, for example, St Michael on the Mount Without, just outside the city walls; Bristol castle; and St John’s Hospital, Redcliffe. Evidence from Maud Baker’s will points also towards an anchoress living at the Blackfriars (Dominican) monastic institution in the early sixteenth century. The Dominicans as an order were very much involved in such pastoral care, offering priestly duties such as communion and confession to women in the nunneries and anchorholds throughout Europe. Similarly, their more reclusive Carthusian brethren engaged in receiving, copying and circulating the writings of holy women in Europe (anchoresses included) from the fourteenth century onwards – the writing of Julian and Margery included. It is in these sorts of contexts, therefore, that we can recognise the motivation of the Bristol vowess, Maud Baker, to bequeath 20s to the nearby Carthusian houses of Witham and Hinton in her will – a highly unusual legacy for a mercantile widow to make.

We know that the Carthusian order tended to have uniform libraries and were frequently involved in loaning out books of spiritual interest to the elite laity (although there is no evidence to suggest this in the case of Maud), but she was likely aware of their support for the writings of holy women and left these two prestigious houses a substantial sum accordingly. Maud also left the same amount to the unnamed anchoress living at the Blackfriars friary during the closing decades of the fifteenth century and early sixteenth century. It may well have been that there was some kind of friendship between these two women, or that Maud’s knowledge of the anchoress had been an instigator in her own decision to become a vowess (a role that seems to have been a rare one in late medieval Bristol). In fact, the only other recorded vowess in Bristol during the same period was Maud’s daughter, Joan, who took her own vow some years after her mother’s death, again pointing towards female lines of influence. Maud’s network of religious women also extended as far as the elite Shaftesbury Abbey, whose abbess, Margery Twynho, seems to have been a friend or acquaintance of hers. In her will, Maud bequeathed to the abbess the luxury item of coral beads overset with silver. The link between the two women is further strengthened by the fact that, in or around 1503, Maud’s stepdaughter, Alice, became a novice at the same nunnery.

It is within such a religious network of pious women that another extant Bristol manuscript emerges, and one clearly shaped to accommodate specifically female spiritual requirements. BCL, MS 6 is a fascinating devotional miscellany dating from 1502, written in both Latin and English by a scribe-compiler named William Haulle, a brother at the hospital of St Mark’s in Bristol and whose signature appears on the front flyleaf. St Mark’s was founded somewhere between 1216 and 1230 under the auspices of the nearby Benedictine abbey to feed and care for the poor, but soon became independent. Moreover, by the end of the fifteenth century the institution appears to have become a significant place of retreat for elite women, very often widows, some of whom lived out the end of their lives there in pseudo-anchoritic fashion as non-professed lay pensioners (corrodians) who were either sponsored or self-funding and who would subsequently provide for the hospital in their wills.

Mary Erler has established that two such women were the related gentry widows, Elizabeth Cornwall (d. 1489) and Jane Guildford (d. 1538). Elizabeth moved to St Mark’s towards the end of her life along with some or all of her five maids, named fully in her 1489 will: Jenet Ive, Maryon Kachema, Jane ap Hopton, Margaret Dolle and Jane Blewet. She was then buried there after her death in or around 1489. Jane, meanwhile, was a woman who, at the end of the fifteenth century, had enjoyed a prestigious position as lady-in-waiting for the deeply pious Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, but by 1535 was clearly living at St Mark’s as a widow. It was in this year that she wrote assertively to none less than Thomas Cromwell, defending the spiritual and physical comfort she has been enjoying at the hospital. There is, however, no evidence to suggest that Maud Baker/Spicer herself ever lodged at St Mark’s as a vowess, but it is clear that Bristol’s devout climate offered opportunities for women like her and her daughter to follow an anchoritic-type life within the world and to offer material support for their parish churches. For others, like Elizabeth, Jane and their maids, it provided them with safe withdrawal and refuge at the hospital of St Mark’s in their old age where they could partake in the rich literary culture offered to them there (another of the brethren, John Colman, was a prolific compiler of books aimed at, or owned by women, as Erler has also established).

MS 6, was compiled and copied by William Haulle at the beginning of the sixteenth century, most likely for another female inhabitant named Joan Regent (d. 1509/10). Joan was another Bristol widow, whose will detailed her ardent desire to be buried at St Mark’s too. Joan’s widespread reading and other participation in the institution’s literary culture is testified to in a number of other manuscripts owned by her, especially those she shared with other women – Katherine Pole, for example, a sister corrodian at the hospital (and whom A. I. Doyle identified in his unpublished PhD dissertation as one of Cecily Neville’s granddaughters). As we also know, Cecily Neville was also an aficionada of women’s devotional writings and bequeathed to another of her granddaughters a copy of Mechthild of Hackeborn’s writing.

MS 6 contains eight separate texts, a good many suggestive of an anchoritic or quasi-anchoritic ‘mixed life’. Of particular note is the opening treatise, Expositio verborum difficilium (Exposition of Difficult Words in the Mass), ideal for helping with semi-Latinate literacy, and a unique Middle English version of the friar-hermit William Flete’s de remediis contra temptaciones, translated as A tretys techyng vs to knowe the dyuersytes of temptacyons. This text was also one of Julian of Norwich’s many sources and its manuscript history shows much evidence of primarily female ownership. William Haulle’s version of this text at St Mark’s is unique in its strong emphasis on the need for the reader to exercise charity and to relinquish showy and elaborate materialism – both highly relevant issues in the lives of those wealthy and privileged widows who resided there. This version also expands considerably upon the Latin original’s suggestion that it is heretical for a Christian not to submit to the judgement of a confessor. It also entirely omits an exhortation for the reader to spend time reading holy scripture, reflecting common ecclesiastic fears about women’s unmediated access to biblical writings. Interestingly, too, on fols 123v-24r, in an insertion entirely unique to his version of the text, Haulle extemporises upon a highly memorable simile in which sinful thoughts are likened to an aggressively barking dog that should be avoided at all costs. Here, it is difficult not to be reminded of the barking dog of the anchorite on Brandon Hill in the Ruddock-Clyve Saint Christopher image, discussed above.

Also included in MS 6 is a version of A Tretis of Discrescyon of Spirites– an important text of discernment tailored towards a woman reader claiming visionary experience of God (and containing some of the issues focused on by Julian and Margery their 1413 meeting). Similarly, a Middle English version of the confessional text, Confiteor deo beate marie, has also been specifically adapted for a woman, who is to beware of lascivious thoughts from looking at ‘a fayre man and shapply’ [a handsome and shapely man].The manuscript also houses a copy of the so-called ‘Oxford Rule’ for anchorites in Middle English, but much simplified for a devout but not necessarily anchoritic audience: this version, like A Tretys, also emphasises that the reader should embrace poverty and charitable donation rather than the benefits of strict enclosure.

MS 6, therefore, was clearly designed to meet the spiritual needs of a woman, although it would, of course, also make suitable reading matter for the spiritual education of new brothers at St Mark’s. That the first woman reader was Jane Regent is further suggested by other extant iconography at St Mark’s, dating from the same period and still visible in the remaining chapel. Now in the nave, a much-faded wall-painting of the encounter between Mary Magdalene (the patron saint of recluses) and the risen Christ in the garden (the noli me tangere scene), alongside images of the Trinity and the Nativity, is to be found, marking the position of a small devotional closet or cell from the period with viewing access to the main altar offered via the type of angled window – ‘squint’ – common to church-based anchorholds. Mary Erler has suggested that it was Joan Regent herself who commissioned and paid for these images while residing at the hospital, as the dates for the paintings coincide with her residency there. In this context, too, as Nicole Rice has suggested in her book, The Medieval Hospital, it may be significant that the first of the manuscript’s Middle English texts – one unique to this manuscript and which focuses on the topic of ‘Tribulacyon [as] the best thing that any man may haue in thys world’ – is memorable for its representation of Mary Magdalene and the Virgin as paradigmatic of the devotional life. That this cell was constructed and used to house women residents, keeping them out of sight while allowing them a view of the main altar, is testified to by the later resident, Jane Guildford, who, in her 1538 letter to Cromwell writes of her ‘lodging most meetest’ at St Mark’s, detailing also the freely-accessible enclosed chapel near the choir, entered via the institution’s cloister.

This material evidence of female presence in St Mark’s, combined with the evidence of MS 6 and its wider contexts, suggests a ready audience of women for the codex, its contents providing appropriate subject matter for pious laywomen and brethren alike to talk in an informed way about religious and devotional matters, in the same way as Margery Kempe had done with Julian of Norwich and many other religious figures almost a century earlier. Thus, although the extant medieval devotional manuscripts of Bristol are few and far between, those that do remain offer us a great deal of valuable information concerning the type of piety practised by the wealthy women of the city. Similarly, when considered alongside the protracted experiences of Margery Kempe in the city in the summer of 1417, Bristol emerges as a vibrant centre, not only for trade and international travel but also as a hub for an exceptional and elite form of literate female devotional practices.

This post prefigures my longer, more formal piece that forms part of the forthcoming new catalogue of medieval manuscripts housed in the Bristol Central Library, edited by Kathleen Kennedy for Boydell and Brewer.

Some further reading: .

Adams, Stephanie Jane, ‘Religion, Society and Godly Women: The Nature of Female Piety om a Late Medieval Urban Community’. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Bristol (2001).

Burgess, Clive (ed.), The Pre-Reformation Records of All Saints’ Church, Bristol, 3 vols (Bristol: Bristol Record Society, 1995-2004).

Burgess, Clive, ‘The Right Ordering of Souls’: The Parish of All Saints’ Bristol on the Eve of the Reformation (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2019).

Erler, Mary, ‘Widows in Retirement: Region, Patronage, Spirituality, Reading at the Gaunts, Bristol’, Religion and Literature, 37.2 (2005), 51-75.

Gill, Miriam and Helen Howard, ‘Glimpses of Glory: Paintings from St Mark’s Hospital, Bristol’, in Almost the Richest City: Bristol in the Middle Ages, ed. Laurence Keen, Bristol Archaeological Society Transactions 19 (1997), 97-106.

Prigeon, Eleanor Elizabeth, ‘Saint Christopher Wall Paintings in English and Welsh Churches, c.1250-c.1500’. Unpublished PhD dissertation (University of Leicester, 2010).

Rice, Nicole, The Medieval Hospital: Literary Culture and Community in England 1350-1550 (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 2023).

Warren, Ann K., Anchorites and their Patrons in Medieval England (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1985).