by Namrata Chaturvedi

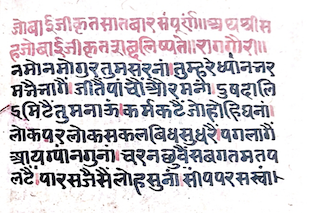

Transcription from an 18th century manuscript of Sahajobai’s verse. Accessed from Rajasthani Shodh Sansthan, Jodhpur. Reproduced with permission.

Dear sister, come let us celebrate with songs of rejoice,

The eternal one has descended in human form of his choice.

–Sahajobai, 18th c. north India

Sahajobai thus sings of her guru’s (master’s) birth. Known as badhāī geet (celebration song), this is one of the many forms of vernacular devotional poetry (bhakti poetry) in India that is largely rhythmic and participatory. The medieval period witnessed the flowering of devotional poetic across linguistic traditions in India. Since then, the names of men saints, gurus, yogis and ascetics are well preserved in public memory and devotional practices. However, the names of women are limited to some saint poets such as Meerabai, Akkamahadevi, Gangasati, Lal Ded, Muktabai and few others. Daughters of Light started as a challenge to identify the names of women mystics who have slipped into the cracks of history.

My writing began on a deeply personal note. In the beginning of 2018, my father dropped his body. This transition was a spiritual rupture for me and I had begun to be haunted by a vacuous force that was gnawing away at the foundations of my very being. After a year of thick darkness, some light began to filter in. In his books and my own readings and notes, I came across the writings of women who were bhaktas (devotees), channels, yoginis and teachers. One word by one word, I found spiritual resonances in their writings. Almost all of these women were unknown or at best known to closed circles of their own spiritual practices. It was then that I resolved to bring the words of my spiritual elder sisters to general readership.

This journey began with two questions regarding the form and language of my writing. My teacher Prof. H.S Shivaprakash resolved one for me by suggesting that I select a general, non-academic writing style for he believed that these names must reach people beyond the scholarly domain. The second question was regarding the choice of language. As my deepest questions come to me in my mother tongue, I wanted to write this book in Hindi. Slowly, this question resolved itself too for I realised that the vernacular traditions are already marginalised and one way to bring women’s voices into the global discourse of women’s writing was to write in English.

With the pandemic beginning as soon as I had gathered some clarity, the pace of my research was arrested. Slowly, whenever I found windows of safe travel, I began to visit different parts of India. Beginning with eighteenth century north India, I was going to trace the evolutions and erasures in women’s spiritual literature from the western plains to the eastern Himalayas. Since my pain had begun with the dissolution of the human body into its five constitutive elements, I decided to dedicate each chapter to one element veritably reconstituting a new body of women’s voices. Out of the five chapters, three are about women’s writing in sadhukkadī bhāshā (vernacular saint language), Mewari (a language of Rajasthan) and Nepali language respectively. The other two chapters are about original prose writings in English. I chose literature only from the languages that I could directly read and translate from so that poetry could be presented in English for the first time.

My experiences of meeting and interviewing people and photographing old shrines, samādhis (sacred graves), ashrams and temples were filled with the excitement of uncovering layers of cultural amnesia.

Contextualising Sahajobai’s poetry was my first goal. Having lived and composed vernacular devotional poems in eighteenth century Delhi, Sahajobai was a notable figure of her times. She was the renowned disciple of her master Charandas and was the caretaker of a prime spiritual centre of the tradition, a rare phenomenon for a woman to inherit land and the name of her master.

In Hindi bhakti poetry, Sahajobai is not the earliest or the only poet as Meerabai lived and sang around hundred and fifty years before her. However, Meerabai’s poetry has been preserved and written about but Sahajobai ’s songs await sustained scholarly interest and musical renditions. One reason for this is owed to the tenor of their writing as Meerabai’s poetic is marked by the sentiment of desire for lord Krishna while Sahajobai ’s poems are focused on devotion to her guru alone and descriptions of straightforward rigorous yogic practices. This compels us to reflect on our presumptions about women’s devotional writing to see if our aesthetic imagination is ready to accept variegated layers of the spiritual experiences of women.

The other mystics I chose to write about are Bhuribai ‘Alakh’ of rural Rajasthan and Anjana devi of rural Darjeeling. In writing about Bhuribai, I found support from the recollections and anecdotes of people who had been touched by her spiritual presence. Some people have preserved and recreated her life teachings in the form of couplets. There were no writings by her as she encouraged no followers and urged people to stay silent. Upon repeated requests to write her spiritual experiences and realisations, she had just scribbled the name of lord Ram on one page of a blank notebook and smeared the rest with ink. Known as The Black Book, this is a testimony of her silent meditative glory.

Anjana devi’s work was hard to find and I could collect only four long poems of hers as she lived in the Himalayan region where literacy is still a challenge. There were oral lores about her but no copies of her poems even though she had lived in the first two decades of the twentieth century. With bits from India and Nepal, I was able to gather some poems and articles and I have translated all her poems into English.

The fourth chapter is dedicated to the writing of Sr Vandana (fondly known as Vandana mataji) who was a Christian sannyāsī (ascetic) in early independent India. There were many scholarly articles about her but in the Christian community at present, her name wasn’t considered important enough. Indian Christian worldview has moved away from inter-spiritual communion to liberation theology, engaging more with contemporary social and political questions. I was able to visit some Christian ashrams that had been established during her time and I was able to connect with some of members of her extended family.

The fifth chapter is dedicated to two urban women who had not realised their spiritual potential till they met the deaths of their sons. Their life stories are marked by their transformation from victims of suffocating silence to harbingers of hope. In Indian writing, their works represent the genre of life-after-life or ADC (After Death Communication) that has been well developed in the West but has gained currency in India only lately. Khorshed Bhavnagari and Nan Umrigar were pioneers of this mode of writing that has brought closure, healing and hope to countless people, especially grieving mothers.

Writing about Anjana devi was particularly challenging because her poetry has hardly been preserved. My source for accessing her poems were the private papers of P.K Pradhan ji of Kurseong who was devoted to her spiritual persona. Unfortunately, by the time I reached Kurseong, he had passed on. His son generously gave me access to his father’s papers that consisted of some photocopied pages and newspaper cuttings about Anjana devi. The only other source for accessing one poem of hers was a book titled Milkeka Jhilka written by Swami Prapannacharya of Nepal. This time, too, I was a little late for Swami ji had passed on a year ago.

The obliteration of textual histories in Indian Nepali literature can be gleaned from the fact that the hill communities are still struggling for basic resources of education and health. While searching for Anjana devi’s samādhi (sacred grave), we reached a tea plantation village where an elderly man narrated an incident that symbolises the challenges in women’s literary historiography. In early 1990s, a group of German scholars (“white men” as he called them) had come searching for “one Anjana devi’s grave” among the tea bushes. He told us how the village had gathered to witness a “miracle” wherein they had managed to reach an obscure patch with an overgrowth laden grave that the white man claimed to have been that of a great yogini. The villagers hadn’t heard her name before and before their eyes, a chemical was poured on the gravestone and up came alphabets that revealed her name “Anjana devi”! The man had chuckled and I had wistfully smiled, wondering how many more chemicals are needed to burn the rust of historiographical oblivion.

This book is a tribute to the urgency of words, as Anjana devi sings:

Time is wasting O my lord,

In hours, minutes and each second

If you don’t grace my devotion, Lord

My wastage, who will reckon?

Daughters of Light: Journeys with India’s Women Mystics by Namrata Chaturvedi will be published by Rupa Publications in 2025.