by Ayoush Lazikani

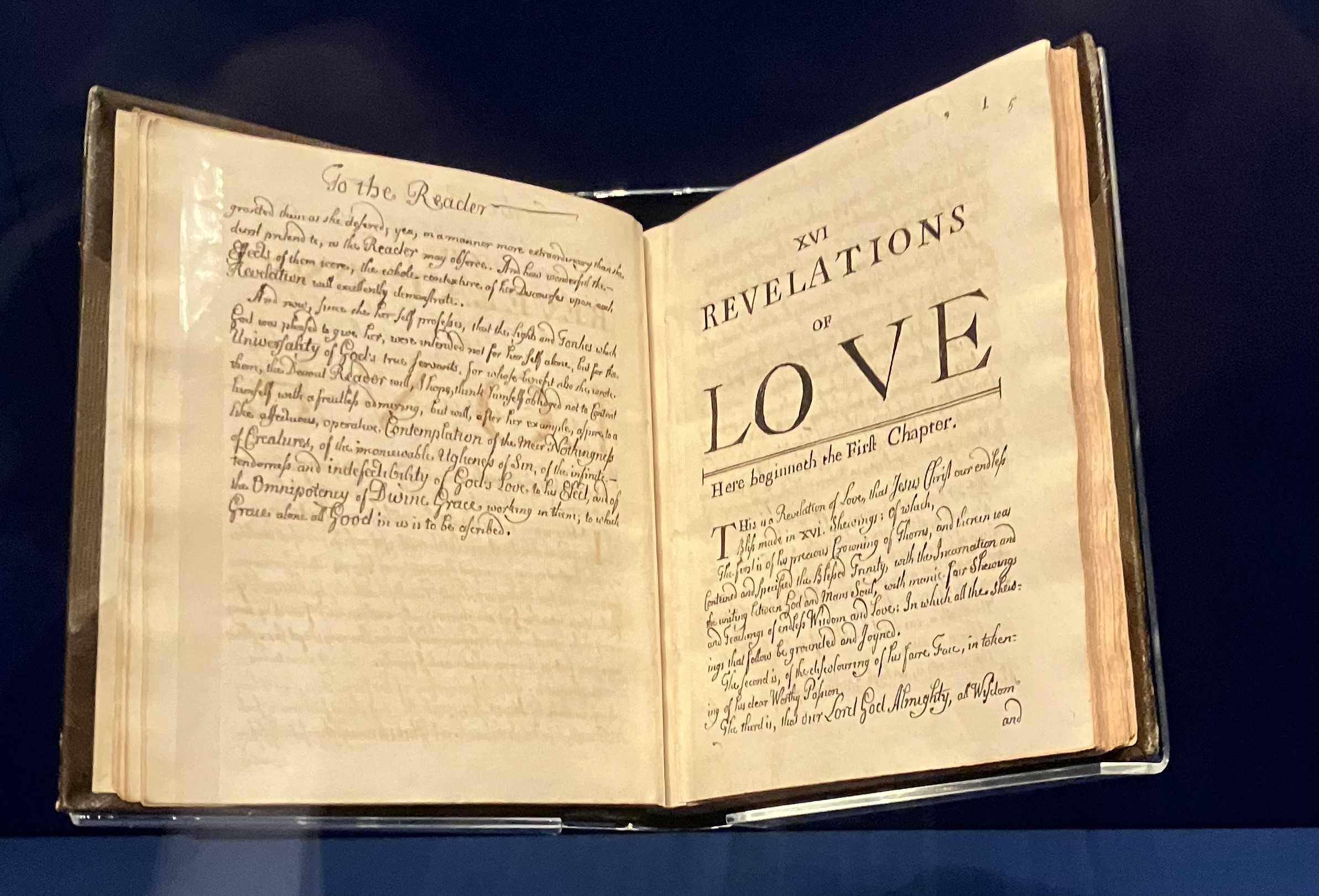

Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love (the ‘Long Text’), possibly Cambrai (France) around 1675, on display at the British Library’s Medieval Women: In Their Own Words Exhibition (c) British Library

A woman has a vision of something like a hazelnut in the palm of her hand, and contemplates that ‘it is all that is made’. This was Julian of Norwich, the first woman to have her name recorded as an author in English. Entering a cell in St Julian’s church in Norwich, one finds a bowl full of hazelnuts—testament to Julian’s striking image of the entirety of creation found in a humble hazelnut. Julian was enclosed there as an anchorite, a recluse, in the cell attached to the church.

Very little is known about Julian of Norwich’s life. She may or may not have been a nun. It is possible she had a child who died in the Black Death, the devastating pandemic of bubonic plague that spread through Europe in the fourteenth century. It was later in life that she chose to become an anchorite, living the remainder of her days in the cell in St Julian’s.

Julian is known for a prose work, The Revelations of Divine Love, in two versions (the ‘Short Text’ developed into the ‘Long Text’). Alternatively, we might see these versions as two distinct works. Julian tells us that she had a debilitating and life-threatening illness at the age of thirty. This illness provoked a series of visions of Christ’s suffering, love, and grace, and Julian felt compelled to share these visions with her fellow Christians. It is these experiences that form The Revelations of Divine Love.

In this work or works, Julian has a series of sixteen visions. These are visions rich in visual detail, leading one scholar to suggest that Julian ‘reads her vision like a picture rather than a story’ (Denise Nowakowski Baker). In her first vision, Julian sees Christ’s crowning with thorns, and this event is relayed in vivid detail. She sees the ‘red blood trickling down from under the garland, hot and freshly and most plenteously’. In the eighth revelation, Julian sees a close-up of Christ’s face as he dies, watching it change colour and losing all its moisture.

But such suffering is always combined with the gentleness of Christ’s abiding and all-encompassing love. In the tenth revelation, Julian has a vision of Christ gazing at the terrible wound in his side. He then leads her inside his body, his side acting as a kind of opening. There, Julian sees a place that is ‘beautiful, and delectable, and large enough for all humankind that shall be saved to rest in peace and love’. She even hears Christ speaking to her, uttering the following words of love and compassion: ‘My darling, behold and see your Lord, your God who is your creator and your endless joy; see what pleasure and bliss I have in your salvation, and for my love rejoice now with me’.

Entering Julian’s reconstructed cell (c) Diane Watt

To this day, visitors can see and walk in a reconstruction of the cell where Julian spent her later years, ruminating and writing on her extraordinary visions. The church, which in the Middle Ages was situated in the thriving mercantile area of Conesford, had been destroyed in the Norwich Blitz in 1942, but was rebuilt and reopened in 1953. Since then, it has remained a home to Julian’s legacy.

Further reading

1.Translation

Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love, trans. by Barry Windeatt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015)

2.Secondary Reading

Denise Nowakowski Baker, Julian of Norwich’s Showings: From Vision to Book (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

Santha Bhattacharji, ‘Julian of Norwich (1342-c.1416), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2014), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/15163; Accessed 19 March 2025.

Hetta Howes, Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women (London: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2024)

Elizabeth Ruth Obbard, Through Julian’s Windows: Growing into Wholeness with Julian of Norwich (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2008)

Janina Ramirez, Julian of Norwich: A Very Brief History (London: SPCK, 2016)