by Peter Mackie

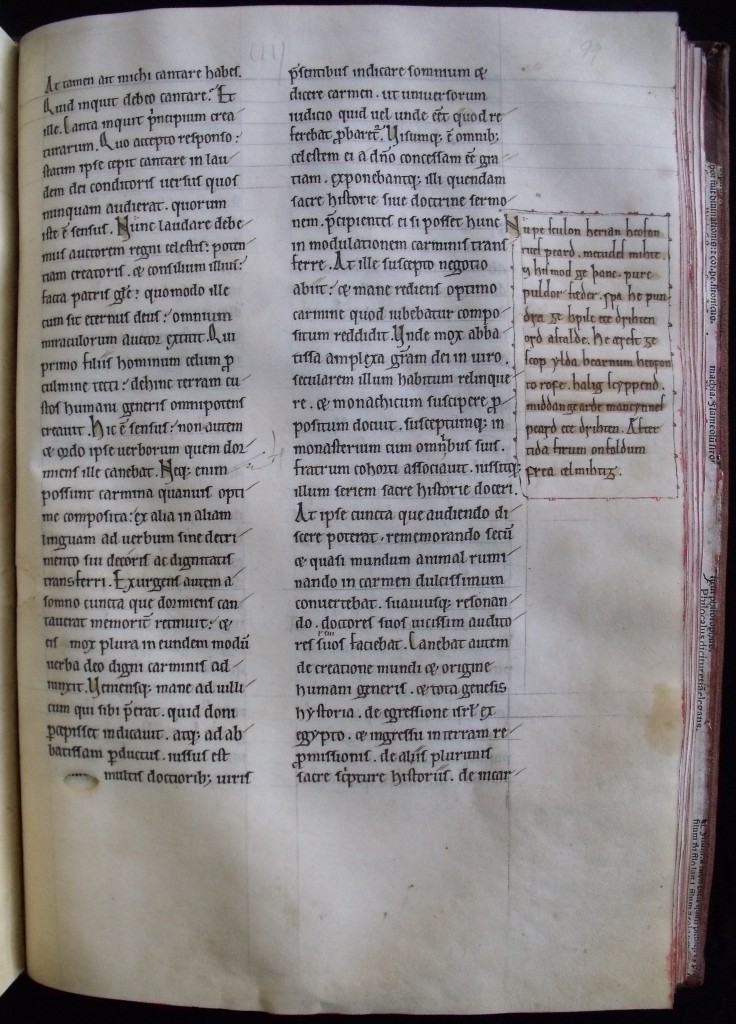

Bede’s Ecclesiastical History (Caedmon’s Hymn) in Oxford, Magdalen College, MS.Lat.105. Credit: The President and Fellows of Magdalen College, Oxford. Reproduced with permission.

Hild of Whitby, often known by the latinised version of her name, Hilda, was the founding Abbess of Streanaeshalch, now known as Whitby, high on the North Sea cliffs above the safe harbour where the River Esk reaches the North Sea. Today, Whitby Abbey is a striking ruin, towering above the coast. It is maintained by English Heritage and there is a visitor centre on site. Whitby Museum is located near by in Pannett Park.

Hild was the daughter of Breguswith and Hereric, nephew of the first Christian Northumbrian king Edwin, so was of noble birth. She was instructed in Christianity by Paulinus, the first bishop of York and thus was part of the very first wave of Northumbrian Christianity.

Little is known of Hild’s early life. One of her sisters, Hereswith, was mother of Ealdwulf, king of the East Angles, but had retired to live as a nun in France. Hild did not become a nun until she was 33, she did intend to join her sister but was called back by Aidan, bishop of Lindisfarne. Beginning her religious life first on the north bank of the River Wear, she became abbess of the recently established monastery at Hartlepool, where she was visited regularly by Aidan and other learned men.

The ruins of Whitby Abbey seen from the south east. Credit: Juliet220, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

From Hartlepool, Hild moved to Whitby a ‘double’ monastery of women and men with a woman in charge; her position as abbess reflects her prominence in the Northumbrian Church. Today Whitby seems on the edge of things, but at the time Whitby had a prominent place on the sea routes to the south and to Rome. Perhaps that, along with Hild’s reputation was why it was chosen as the venue for the Synod of Whitby at which the Northumbrian kings chose to accept the Roman date of Easter.

Hild’s contribution to early medieval literary culture centres on her patronage of Caedmon, the earliest English poet whose name has come down to us. Caedmon was an illiterate farm-worker at the abbey was called on in a dream to sing a song about the Creation of the world. Caedmon, who had previously avoided singing at feasts, composed some verses. He was brought to Hild who believed that Caedmon had received a gift from God.

Hild recognised that Caedmon’s verses would assist the process of converting the people of Northumbria to Christianity because they could be sung at feasts. We know that Hild used her connections to distribute the hymn widely because the vernacular text survives in 21 versions in different Anglo-Saxon dialects which points to it having been used widely across England.

The Hymn itself consists of just nine lines it is theologically conventional, telling the Christian story of creation in a simple and memorable form.

The lasting importance of the poem to the English medieval church is exemplified in a 12th century Latin manuscript at Magdalene College, Oxford (Magd. MS.Lat.105, f.99) where a vernacular version has been added to the account of Caedmon’s story.

But Whitby was not just a centre for missionary work, it was also very much a centre of learning, probably the pre-eminent centre for learning in Anglo-Saxon England. After Hild’s death, a life of Pope Gregory the Great was written at Whitby linking this wind-swept corner of Northumbria with Rome, then the heart of Europe.

Further Reading

Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, ed. Judith McClure and Roger Collins (Oxford: World’s Classics Series, 1994).

Clare A. Lees Gillian R. Overing, ‘Birthing Bishops and Fathering Poets: Bede, Hild, and the Relations of Cultural Production,’ Exemplaria 6.1 (1994): 35–65.

Daniel Paul O’Donnell, Cædmon’s Hymn (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2005)

Andrew White, A History of Whitby (Cheltenham: The History Press, 2019.