In Week 7, before the Easter break, I was due to teach on the topic of gender in my Level 5 Security Studies module. I was extremely reluctant to perform the same lecture format as usual for this particular topic and so spent a few hours putting together some contemporary sources (Twitter feeds, newspaper reports, video clips) to stimulate debate.

I chose to begin the session by drawing attention to the popular ‘Everyday Sexism’ Twitter feed, which has thousands of followers and hundreds of contributors. The point of highlighting this source was to reinforce the political nature of everyday life and the pervasiveness of unequal, gender-premised power relations in society. As I scrolled down the feed, however, one particular tweet stood out. It contained a photograph of a meme that had been featuring on Facebook walls over recent weeks. A headshot of a smug looking man was accompanied by the following text: “Go ahead, tell the police. They can’t un-rape you”. The response from the class was, on the whole, one of laughter.

It’s at times like these that lecturers have to think on their feet to avoid reinforcing the very socio-political inequalities to which they seek to draw attention. It’s what is sometimes called a ‘teaching’ or ‘teachable’ moment. Why was it, I asked, that it was OK to laugh at a ‘rape joke’? Was there a broader ‘rape culture’ in the United Kingdom? And what, if any, are the connections between finding humour in the topic and actual sexual crimes?

In 2011 research on so-called “lads’ mags” made national headlines. It was revealed that, for the vast majority of people, the language used in such publications is indistinguishable from that of convicted sex offenders. Ordinary Britons were unable to tell if comments selected (and troubling) quotations were part and parcel of the routine depiction of women in FHM, Nuts and Zoo, or the words of a rapist. It was only once they knew the source of the quote that their feelings of association with and support for such language altered accordingly.

While the link is more akin to ‘conditions of possibility’ than ‘causation’, there exists a clear relationship between a culture in which violence towards women is normalized and actual sexual crimes. Perhaps nowhere was this point better made than in the news story which had broken the day before the class. In Steubenville, Ohio, two teenage boys had been convicted of rape. The details of their crime are horrific enough on their own to speak to the importance of understanding the relationship of gender and security. However, two other features of the story were particularly troubling, due to their widespread implications and indications.

First, as news broke of the story and its background, it became apparent that members of the community had attempted to protect the two boys in order to ensure their promising football careers were not damaged. The victim was targeted in an attempt to silence her. Second, media coverage of the trial and its outcome was overwhelmingly focused on the plight of the boys and the sad loss of their freedom, which had resulted from an apparent ‘error of judgment’. Photographs, punditry and reporting all contributed to the construction of a narrative from which the victim and the crimes she had suffered were absent or downplayed.

As we discussed the story, students began to understand the reasons for my surprise and alarm at their laughter. While I certainly wouldn’t argue that gender relations must be exempt from comedy, we would hope that humour has a critical edge that serves to challenge dominant and dangerous power relations (even through irony), rather than contribute to them. At least some of the students in my Security Studies module share that hope. Two of our doctoral researchers – Sam Cooke and Katharine Wright – certainly do. They joined me in the lecture in order to help encourage students to think critically about gender and security.

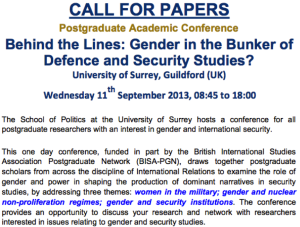

In the School of Politics we are extremely lucky to have an emerging cluster of experts on gender and security amongst our doctoral researchers. Several of them are organizing what promises to be an interesting and important conference on the topic, to be hosted at Surrey on 11th September 2013. For further details, visit the conference website: genderandsecurity.wordpress.com. And to submit an abstract, email: Annie Waqar by 21st June 2013.