I’ve had a small flurry of late-autumn events of late, including a talk at the Institute of International and European Affairs in Dublin (podcasted here) and a workshop here at Surrey on Croatia’s membership of the EU, organised by CRonEM.

In these events, we have talked as much about current events across the Union as we have about the more specific matter in hand. Thus, Croatia can learn much from the UK about how not to make gains from membership, just as the need to engage eurosceptics in the EU process is driven by contingent factors, just as much as structural ones.

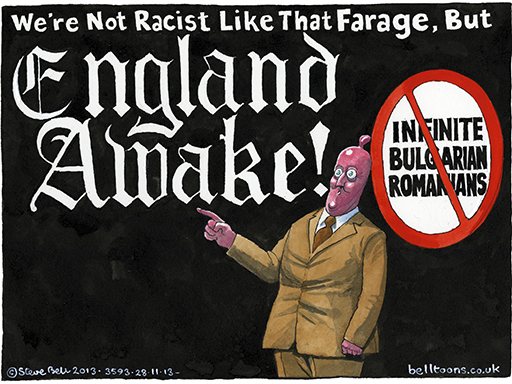

David Cameron’s pronouncements on limiting access to benefits to Romanians and Bulgarians, and to more general curbing of free movement, are a case in point. With Labour acquiescence in the matter, this is driven by domestic politics and the looming European elections, with any sense of a European policy scarce to be seen. Thus, Commissioner László Andor’s comments that the UK risked being seen as a ‘nasty’ country were just as predictable as the backlash to them.

To say that this is unproductive is both unstated and to miss the point. Relations between London and the rest of the EU look less functional than they have since Cameron’s January speech, when there had been the realisation that renegotiation might require a background of trust and collaboration. Even with murmurs of support for reform from the Dutch, Germans or Italians, there is still not nearly enough momentum behind that agenda to turn it into something effective.

Indeed, it is the sense that the UK is on a hiding to nothing that should cause most concern.

Free movement is the pivot of European integration, the cornerstone of economic integration and trade liberalisation. These last two have consistently been at the head of British interests in the EU (pace some concerns on the Left in the 1960s and 1970s) and successive British governments have pushed to protect them, in the face of often strong opposition. Thus, to make an about-turn on this looks very much like cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face, especially when one considers that 2.2m Brits live in other member states.

Moreover – and precisely because it is a cornerstone – free movement isn’t going to be limited. Firstly, there is certainly not the unanimity needed to revise the treaties, and secondly, there is no appetite for the other concessions that would be needed to pay-off other member states. In short, the Union is locked into free movement for the foreseeable future.

Indeed, there has to be a question mark over whether Cameron’s proposals can be made to conform with EU law themselves, given the need for non-discrimination.

Ultimately, the current episode presents itself as yet another example of the failure of the British political system to internalise the logic of European integration. Rules have to be applied fairly and equitably: that implies that all parties must abide by them. For a country that brought the notion of the rule of law to so many other parts of the world, one would hope that this was not too hard a lesson to learn. Sadly, political exigency seems to matter more than principle here.

Pingback: Playing the EU game: complicity or getting your way? | Politics @ Surrey