This is my contribution to the latest UK in a Changing Europe report on “The European Elections and Brexit“, but with some added visualisation, because, well, why not?

One of the paradoxes of extending the Article 50 deadline has been that more attention has been paid to the consequences of British MEPs being absent from the European Parliament than to their presence. But with the distinct likelihood that they will not only be elected but also will take up their posts from July, what impact might they have?

Since the shift to direct elections in 1979, the European Parliament has become progressively more important in the EU’s institutional architecture. That is particularly evident in the period following European elections.

The first step is the formation of the new Parliament itself. By the time of its first sitting on 2 July, the various national party groups of MEPs will have made choices about which political groups in the Parliament they will sit with. These bring together parties with similar ideological backgrounds and, crucially, are central to the operation of the Parliament itself. The size of a group determines not only its weight in plenary votes, but also the number of official posts it can have within the Parliament. These include committee chairs, rapporteurs (who write reports) and members of the bureau, who handle the administration of the institution. Bigger groups also get more speaking time in debates, plus they receive more funding to support their day-to-day work.

In short, being in a group matters and being in a bigger group brings additional benefits. Having British MEPs available thus makes a difference at this early stage.

In the 2014-19 Parliament, British MEPs from UKIP were essential in getting the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) over the line of the minimum numbers of members required (25 MEPs), while Tory MEPs form the largest single party within the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR).

The dilemma for MEPs from other member states will be whether to make use of their British counterparts to get access to those roles and opportunities, when they might find they lose them when the UK leaves, possibly very shortly afterwards.

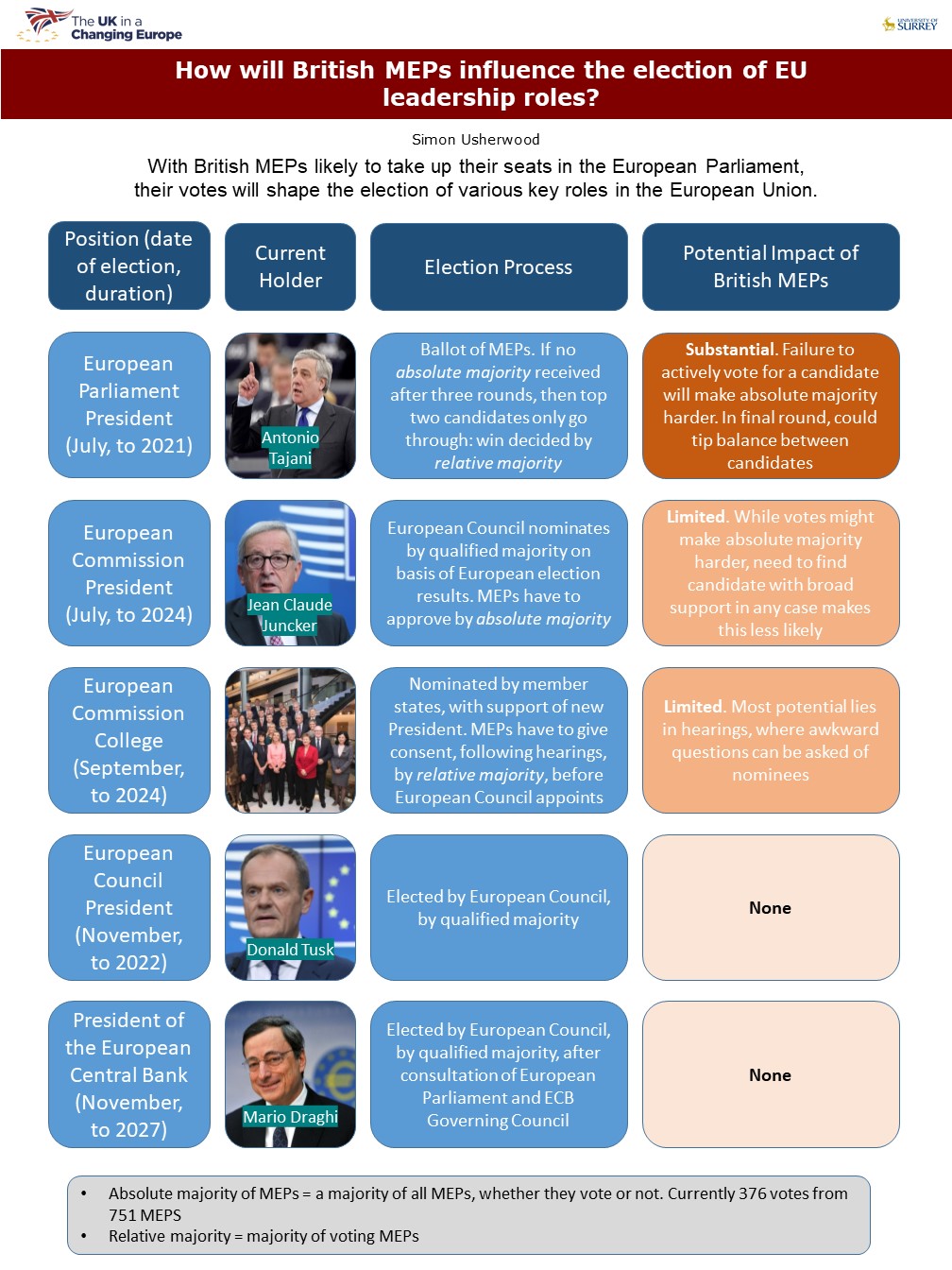

This matters beyond the Parliament itself because, once formed, it becomes the Parliament’s role to select the new European Commission.

In 2014, the groups put forward individuals to be their nominee to become Commission president, the so-called Spitzenkandidaten: they committed that the nominee of whichever group received the most MEPs would be the Parliament’s only acceptable person for that post (the Parliament having to sign off the choice of the member states). This led to Jean-Claude Juncker’s election that summer.

While there is less certainty that this process will happen again this time around, the possibility remains.

So British MEPs could become important once more. Here it will be Labour MEPs who matter most, because they belong to the centre-left Socialists & Democrats (S&D), which might become the largest group if Labour stick with them. Unlike the Parliament’s internal allocations, which can be revised with changes in group sizes, a Commission president, once elected, is there for a whole term, until 2024, so this really matters. This is true particularly because the president then gets to be closely involved in choosing the rest of the commissioners, ahead of parliamentary hearings and approval.

As a result, British MEPs could have an impact on the institutional make-up of both the Parliament and the Commission long past their departure. Even if party groups don’t want to have British MEPs in their ranks, their votes will still count and may swing results.

All of this comes well before we even start to consider the more mundane effect of British MEPs on the work of the Parliament, in day-to-day voting.

Whether or not they are part of groups, the votes of the 73 MEPs will matter on issues both big and small. In most cases, that will be shaped by ideological positions, but there may be votes that produce alignment along national lines. Most obviously, there may be legislation that will have a material impact on a post-membership UK: do British MEPs then vote based on what is best for the EU or on how it might affect the future relationship between the EU and the UK? Do they seek to make that relationship more or less problematic?

This will likely be more of a problem than in previous Parliaments because of the changing composition of MEPs. The long-dominant centre-right and centre-left groups will be less able to command the robust majorities of the past, even with more collaboration with the liberal grouping. The composition and the attitude of British members will count for a lot in this calculation.

Behind all of this is a more basic tension for the EU. In demanding British participation in the European elections, they have stressed the importance of fulfilling treaty obligations and the value of participative democracy for all. To deprive British voters of their vote and their representatives cannot be defended in democratic terms. The flip side of this, however, is that those representatives have to be able to exercise their normal powers: to make decisions and represent their voters’ opinions and interests. As the EU will see through this year – and beyond – that means having to accept that there will be difficult moments and hard choices.