A recent conference at the University of Surrey, hosted jointly by cii – The Centre for International Intervention – and the BISA IR2P Working Group, “20 years after Kosovo: the prospects for and limits of, international intervention”, considered the lessons learned from the NATO intervention in Kosovo in 1999 and its aftermath, in the context of the concept of “The Responsibility to Protect” (R2P), adopted by the UN in 2005. This is a personal reflection on the issues that were discussed.

Even though Kosovo predated R2P by a couple of years it was one of its precursors (the other major one being the Rwandan genocide) and in a sense was the high water mark of the determination to protect people from atrocity crimes that inspired the Canadian government to set up the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS), which towards the end of 2001 produced the R2P report. Despite not being authorised by the UN Security Council (UNSC) the intervention was considered to be legitimate (a Russian attempt to condemn it in the UNSC failed decisively). However, the spirit of R2P has been conspicuously absent in the way the UNSC has dealt with subsequent crises in Darfur, Syria, and Myanmar, to name but some of the worst cases of systematic human rights abuse since 1999.

The NATO intervention in Libya in 2011 was held up by some as an example of R2P in practice, but even though the three words “responsibility”, “to”, and “protect” appeared in UNSC Resolution 1973 authorising the intervention these were directed at the Libyan regime of Colonel Gaddafi; this pattern has been repeated it in many similar Security Council resolutions and reveals that there is no desire on the part of powerful states to acknowledge any obligation on their part to intervene – as opposed to having the freedom to choose when to intervene and when not. And the consequences of the Libya invasion were hardly an advertisement for R2P – not least because Libya reinforced Russian and Chinese opposition to any UN intervention in Syria.

Curiously the UK government, long an ardent champion of the moral principle of “humanitarian intervention”, chooses now to assert this as a legal norm and a unilateral right rather than seeking to remind Russia and China that they, along with all the other members of the UN, signed up to the collective responsibility of R2P in 2005. This might appear to conflict with seeing the latter established as a universal norm; indeed, it could be seen as undermining it.

So, is R2P dead, especially in what may be a “post-liberal world order”, where the prevailing narrative is one of countering terrorism? Conference papers considered new ways in which R2P might be understood, e.g. in terms of obligations to refugees where direct intervention is not possible. Other ideas included P5 members committing to a “responsible veto” in the UNSC (one of the ICISS recommendations, but not adopted by the UN), achieving greater integration with other normative frameworks such as the Protection of Civilians or Women, Peace, and Security, which together resemble an à la carte menu rather than an interlocking set of commitments. Regional level action, where consensus may be easier to achieve than in the UNSC, was also discussed. These are all important ideas, but it is hard to avoid the conclusion that realpolitik, rather than global solidarity, is the dominant force in world politics at the present time.

Nor is the example of Kosovo itself as ringing an endorsement of the principle of R2P as it might appear, if one considers the aftermath. The conference organisers had made sure that local voices from Kosovo were present and the story they told was of a society struggling to make progress despite huge amounts of external assistance since 1999. This was partly because the long term goals of the intervention were never clear, partly because external intervention did not address internal fault lines in Kosovar society, partly because the geopolitics have not changed (the P5 veto problem remains, but now it relates to international recognition of Kosovo). In other words there has been no meaningful reconciliation of the forces that led to the conflict, neither internally nor externally.

In addition, the need for Kosovo to present a positive aspect to the external world, in order to increase the chances of international recognition (and in particular eventual membership of the European Union) prevents gritty political problems from being aired and addressed publicly; political leaders both within and outside Kosovo collude with a myth of progress that fails to do justice to the underlying reality. Finally, crimes of sexual violence and other war crimes committed during the conflict remain unpunished, leading to a lasting sense of injustice.

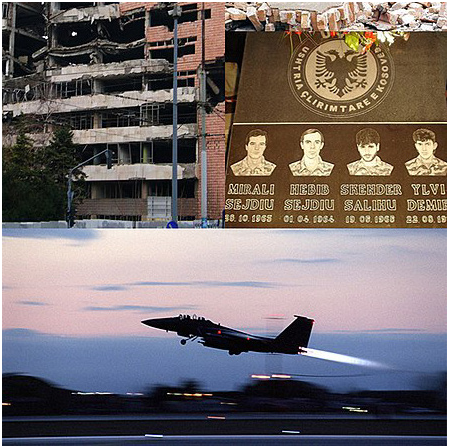

All of this is a salutary reminder that “winning the peace” is as much of a challenge as winning the war, which may be relatively easy (although it took a 78 day bombing campaign, which severely degraded infrastructure inside Serbia itself as well as in Kosovo before NATO was able to bring Milosevic to the negotiating table – this of itself led to considerable deprivation among the civilian population in Serbia, which continued to suffer for many years after the end of hostilities). And in response to the NATO bombing campaign the Milosevic regime stepped up its attacks on civilians, leading to the mass movement of refugees across the border into Macedonia and Albania plus an unknown number hiding from Milosevic’s forces within Kosovo itself.

These were all unintended consequences of the NATO action, and they were due in large part to Milosevic’s cynical disregard for the human rights of the Kosovars, but that does not entirely excuse the Alliance. We expect Western powers to act with foresight. Kosovo was perhaps not the worst case of poor anticipation, but later the lack of understanding of the local context that characterised the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the NATO bombing of Libya in 2011 fall far short of what one might call “responsible intervention”. Policy should be based on evidence, not ignorance.

This should not be a counsel of despair. The impulse to protect people from mass atrocity crimes is central to our shared humanity, and R2P is a powerful expression of that. But there is evil in the world as well as good and it will not always be possible to “save strangers”. Central to the concept of R2P is the notion of “sovereignty as responsibility”, and that is why Pillars 1 and 2 of R2P (strengthening local accountability and capacity) are as important as Pillar 3 (external intervention). Putting more effort into conflict prevention should be a key part of advancing the R2P principles. More and better international diplomacy and mediation are essential; once the P5 is locked in dispute, as it was from the beginning over both Kosovo and Syria, it is wishful thinking to imagine its members will exercise their shared responsibility for protection. Something that is required to be done in the name of the UNSC can hardly happen if the P5 is at war with itself. Addressing that problem would arguably have the greatest impact in terms of making a reality of R2P.