I take it as a positive sign that even my more tangential thoughts about UK-EU relations have popped up before in my brain: I was going to name this post eppur si muove, but I seem to have done that back in 2013.

Sorry, Galileo.

But the idea of a system that works despite everyone saying it doesn’t (or can’t) is still a useful one for thinking about Brexit.

If we step back from the day-to-day maelstrom of it all, we do see that the UK is slowly progressing through the steps of Brexit.

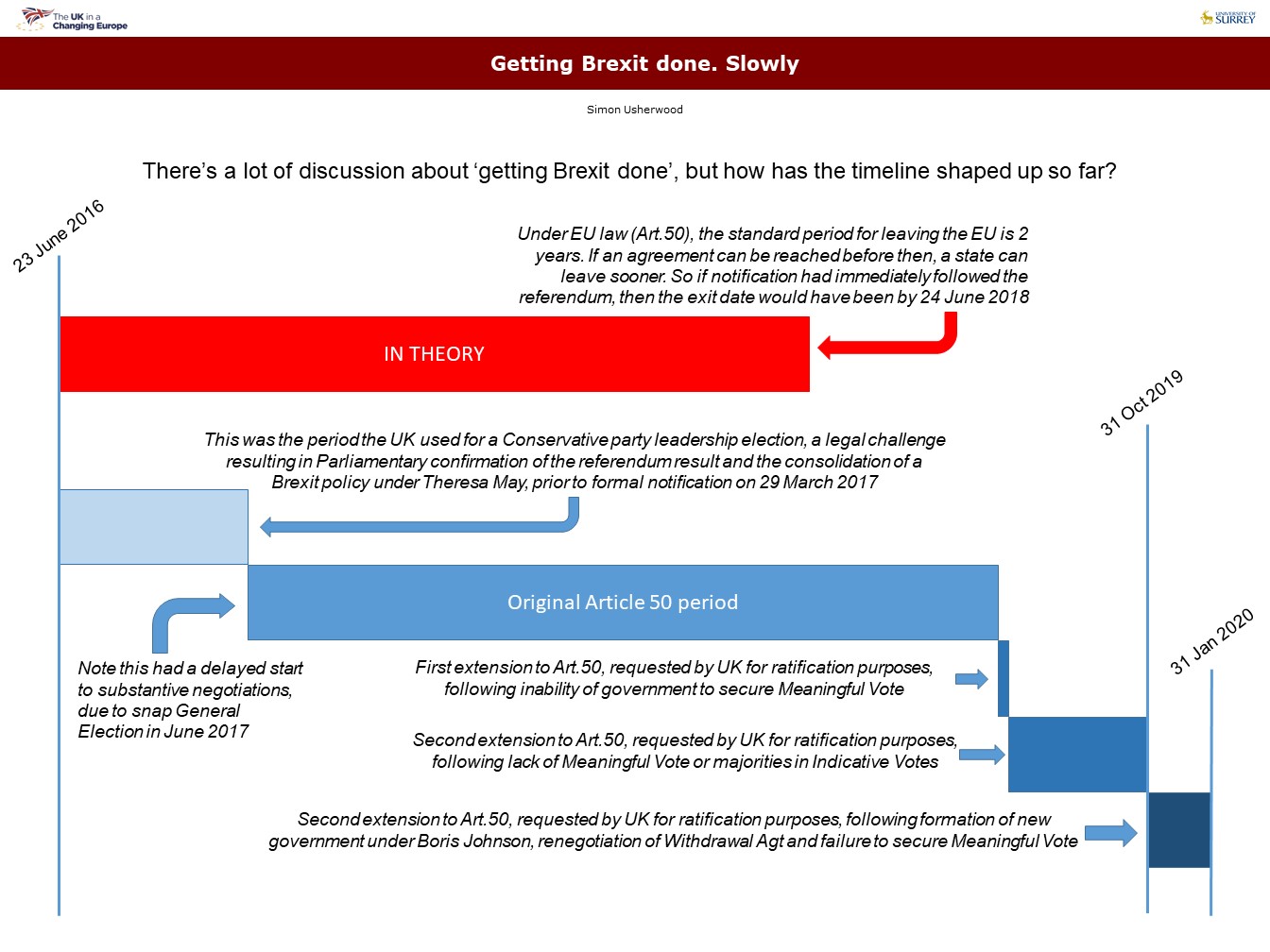

Yes, there are plenty of delays, as I set out in a graphic the other week, but it’s easy to focus on those delays rather than the progress:

Consider that in the first phase of Brexit – withdrawal from the EU – the parties have now done everything apart from ratifying an agreement.

That means the UK has made a decision by referendum to leave, confirmed that in Parliament, notified the EU under Article 50, negotiated a text, re-negotiated it and got the domestic ratification to a second reading.

For a process that is supposed to be stuck, that’s a lot of movement, especially against the benchmarks of those who supposed a text could never be concluded.

Sure, the hurdle of securing Parliamentary ratification is a major one – indeed, it’s nominally the cause of the present General Election (itself the second since the 2016 referendum) – it seen in the wider context, it’s not the only part of the picture.

Indeed, I’d argue that the underlying trend of Brexit to date has been one of progressive, if erratic, movement through the process as it might be understood abstractly.

By this, I mean the UK decides to leave, works through to a withdrawal agreement, leaves, then works on a future relationship.

Each of the many crises the UK has seen since 2016 has ultimately resulted in that path being stuck to.

That’s not because of some masterplan, but rather because no political force in the political arena has been able to come up with an alternative that carries sufficient weight to redirect things. In short, policy advances because no-one’s got a better idea.

In this, Brexit maps very closely to the broader nature of British European policy: contingent and reactive, rather than strategic and agenda-setting.

That Brexit has followed this same model is both unsurprising and disappointing. It speaks to the lack of engagement by politicians with the potential of this moment to escape this particular rut, and to work to create a genuine national debate about this country wants to be.

From all we’ve seen of the general election campaign so far, that engagement is still to be created and we risk bumped down the long path of Brexit without any real thought as to what it’s all for.