This is the big question of late 2020 in Brexit-land. All summer and into the autumn, we’ve have multiple briefings, this way and that; some setting us on the road to a rapid settlement, others pointing towards whatever euphemism-of-the-day we might have for a no-deal outcome.

So which is it?

Rather than try to list and weigh up all the possible factors, I’ll instead try to focus on the more inflexible and mechanical aspects that might be in play, since these appear to be increasingly important.

Central in these is our old friend, time.

From the very start of the process, before the referendum was even held, it was generally agreed among researchers that this would be a long-term set of interactions to get to a new relationship and that Article 50 would struggle to suffice for all of that.

And so it proved: not only were there the multiple extensions of 2019, but the content of the Withdrawal Agreement was very closely drawn to cover only the bare minimum of issues relating to ending UK membership (as opposed to building a new relationship).

The failure of both sides to extend transition back out to its original 20 month schedule with those Art.50 extensions, plus the refusal of the UK to countenance using the one-off extension mechanism this summer, plus the delays caused by Covid-19, all have contributed to one of the more heroic interpretations of what can be done in short order on a deal.

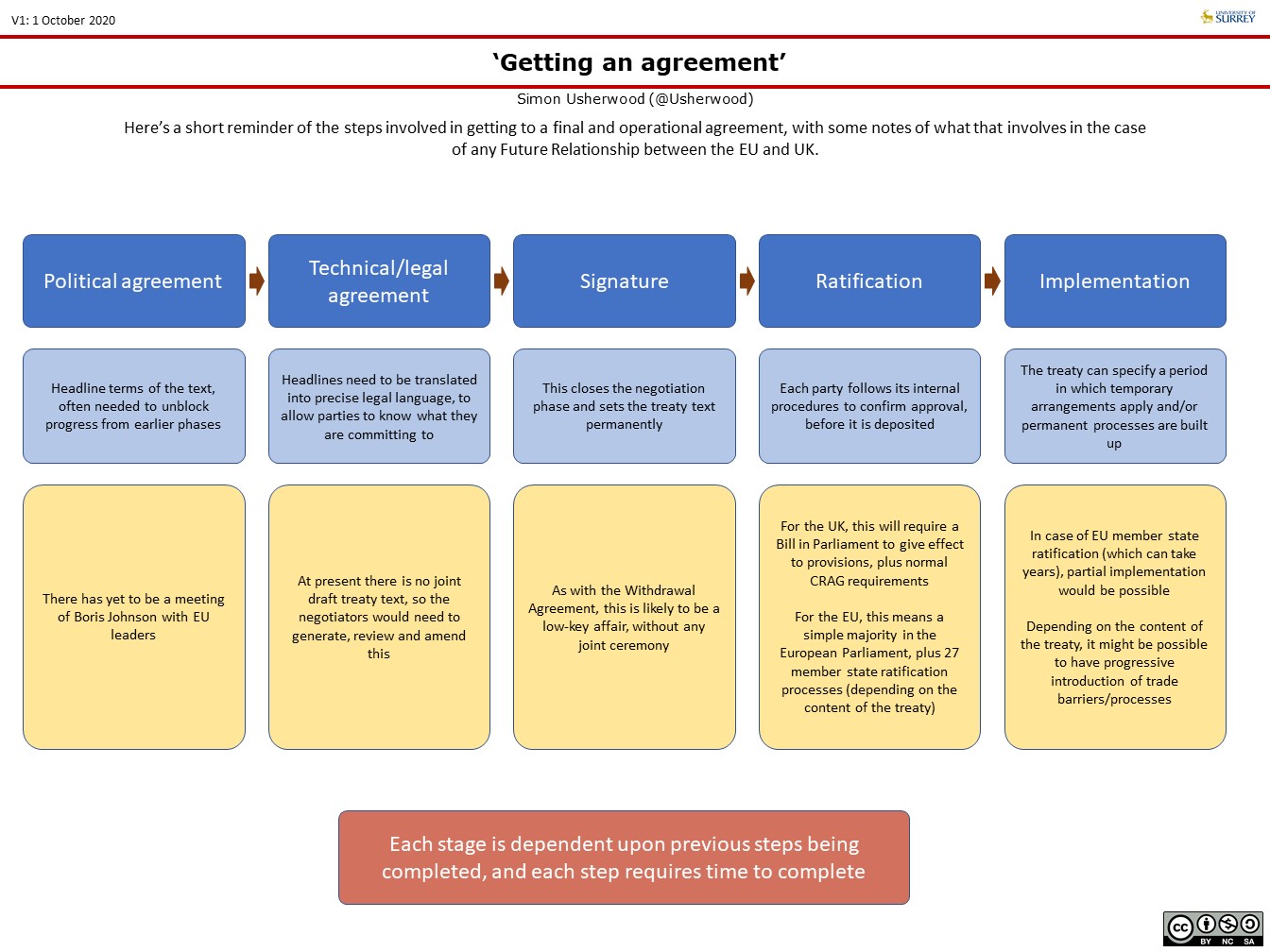

Right now, three months out, we have not only not got a legal text that can be ratified, we don’t have even a joint draft, or a basic political arrangement to allow any of those things to happen.

The simple mechanical requirements for each of those steps take time, time that is increasingly not there: the legal drafting could easily take several weeks, even if everyone agrees with everything (which they won’t).

Which leads to a second key element in the mix, trust.

Just as time has run out, so too has the extent to which each side finds the other credible and constructive. London politicians treat the EU as if everything it does is a trap to entangle the UK and/or reverse the referendum result; those in Brussels and EU27 capitals wonder whether the Internal Market Bill can really be a serious proposition, given that it undermines the entire basis of international agreements.

That trust has been falling for a long time. From the delay in triggering Article 50, to the immediate calling of the 2017 general election; the mess over the joint text and the blowing up of Cabinet over Chequers; the meaningful votes and the extensions; even the popping up of Gibraltar at the last minute: all of this has led EU-UK relations to a pretty bad place.

My personal sense check on this is the Salzburg European Council two years ago. Yes, Theresa May might have made a mess of the attitude/rhetoric, but at least there remained a functioning political negotiation.

So if we know that trust is low, and that trust is very much harder to rebuild than to lose, then we can be confident that this will remain a barrier through the remainder of current talks, whatever they aim for.

And that aim represents a final stable factor: the lack of difference in outcomes.

If we imagine a deal is concluded, and one on UK terms, then we would have to note that there would still be very extensive contraction of UK-EU alignment and a rise in barriers to economic, political and social interactions. The UK government is asking for a very minimal relationship, partly because it wants to limit the ability of the EU to make cross-linkages in the current negotiations.

As much as a no-deal would come with huge costs, so too would a deal be linked with smaller, but still substantial, downsides.

Recall too that this is different from Article 50, when the UK remained a member until the end and neither side had a fall-back to protect its interests. Indeed, that’s precisely why the EU structured the process like this; so that if this current stage failed, at least it would have the legal certainty [sic] of the Withdrawal Agreement.

For the UK, if this is obviously going to hurt either way, and if Number 10 decides that the public might not be too thrilled by the message “we know this hurts, but believe us when we say it could have hurt a lot more”, then the incentive to push for a deal would seem to drop.

Moreover, a deal implies mutual acceptance, which drips the negotiating parties’ hands very firmly into the blood, whereas a no-deal contains the potential to shift blame on to the other lot. Hence, in part, a lot of those briefings I mentioned: we’re trying really hard to make this work, but they’re making it impossible, etc.

Taken together, it’s hard not to be pessimistic about the next months.

Time is running away and there’s no credible mechanism for adding more (even if both sides wanted to), trust is as low as it’s ever been (not helped at by the completion of the Internal Market Bill’s progress through the Commons), and the gains of a deal seem to be now limited to reducing the costs of exit.

Yes, a deal would mean one less headache for both sides, both economically and politically, especially since their asks will not magically disappear as midnight strikes on New Year’s. But as we’ve seen time and again, this is not a rationally-constructed process, but instead one of politics, short-time thinking and the entanglement of many other factors (not least Covid-19).

Put it like this: I never built up some extra food staples in the run-up to the conclusion of Article 50, but I am doing it now.