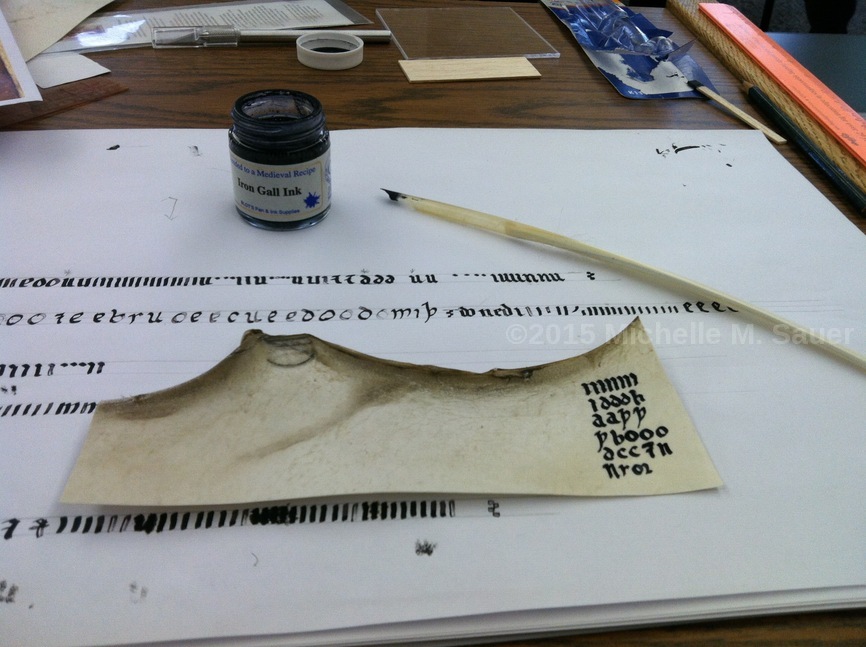

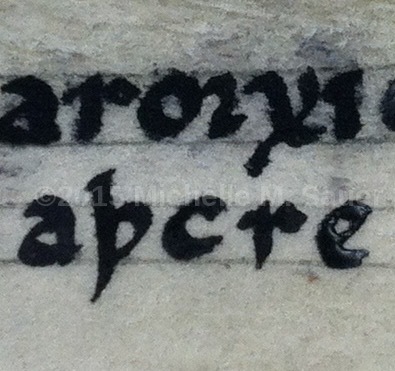

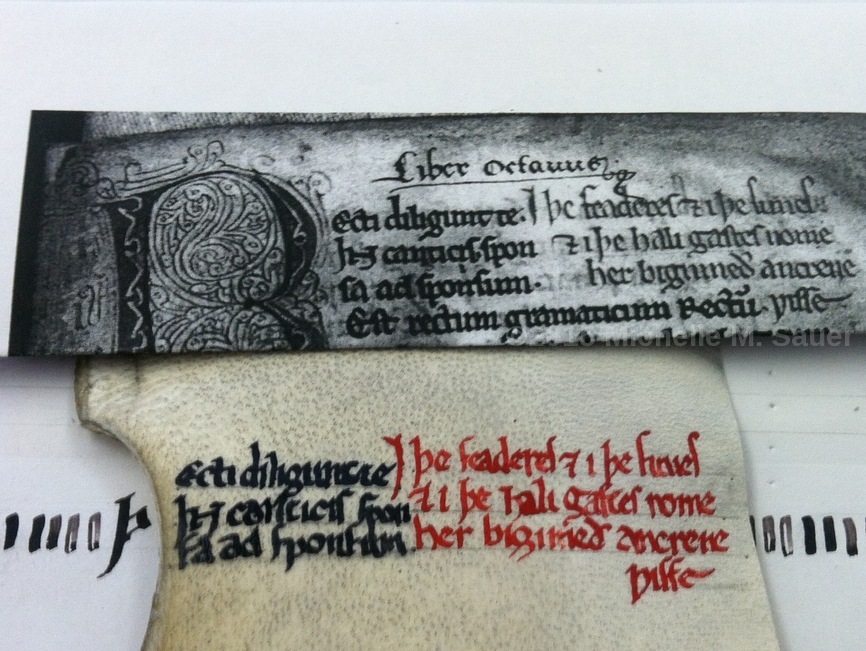

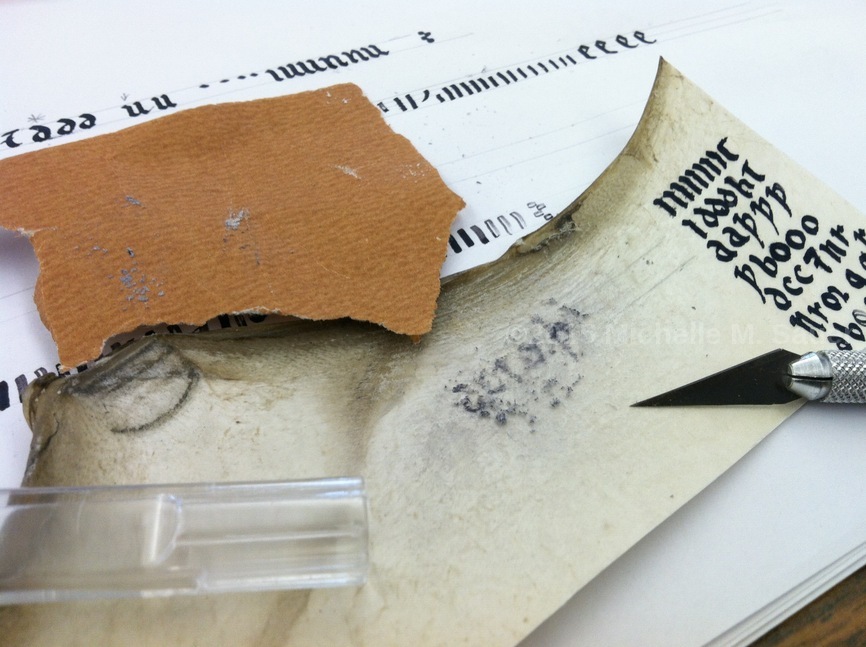

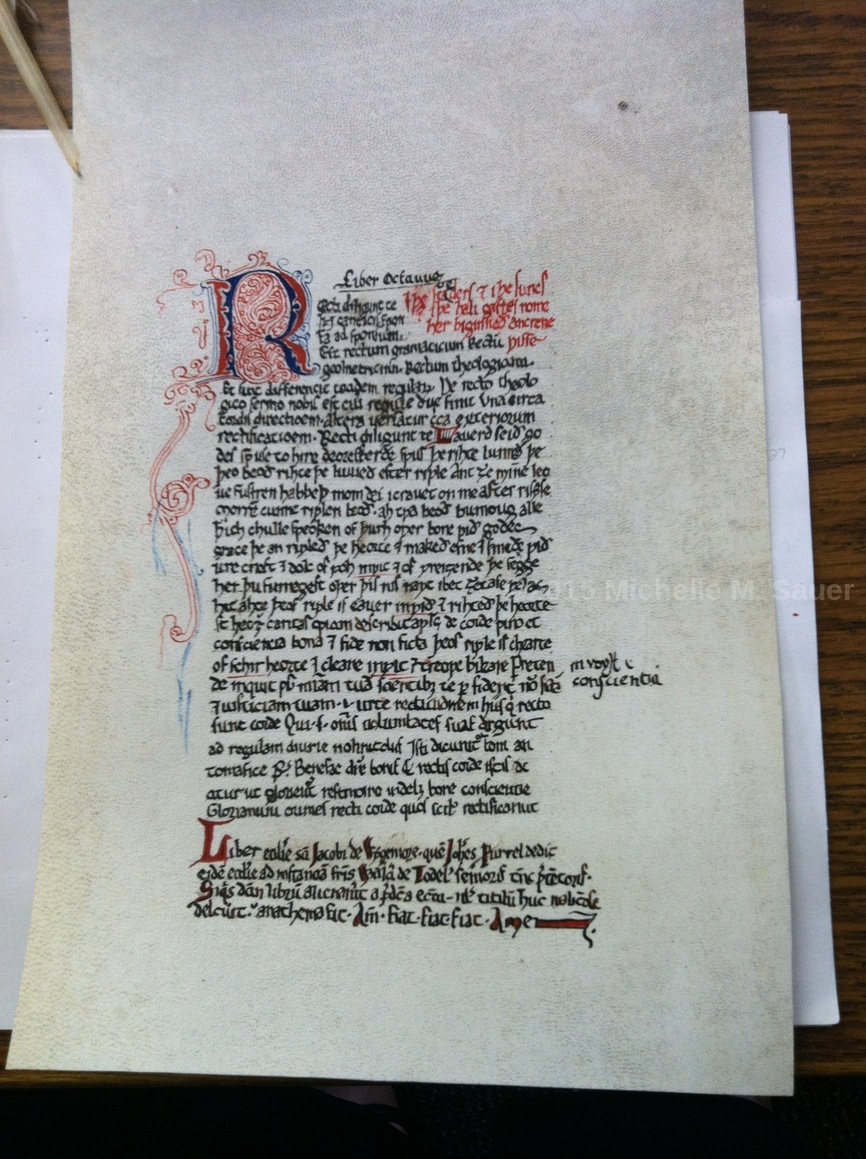

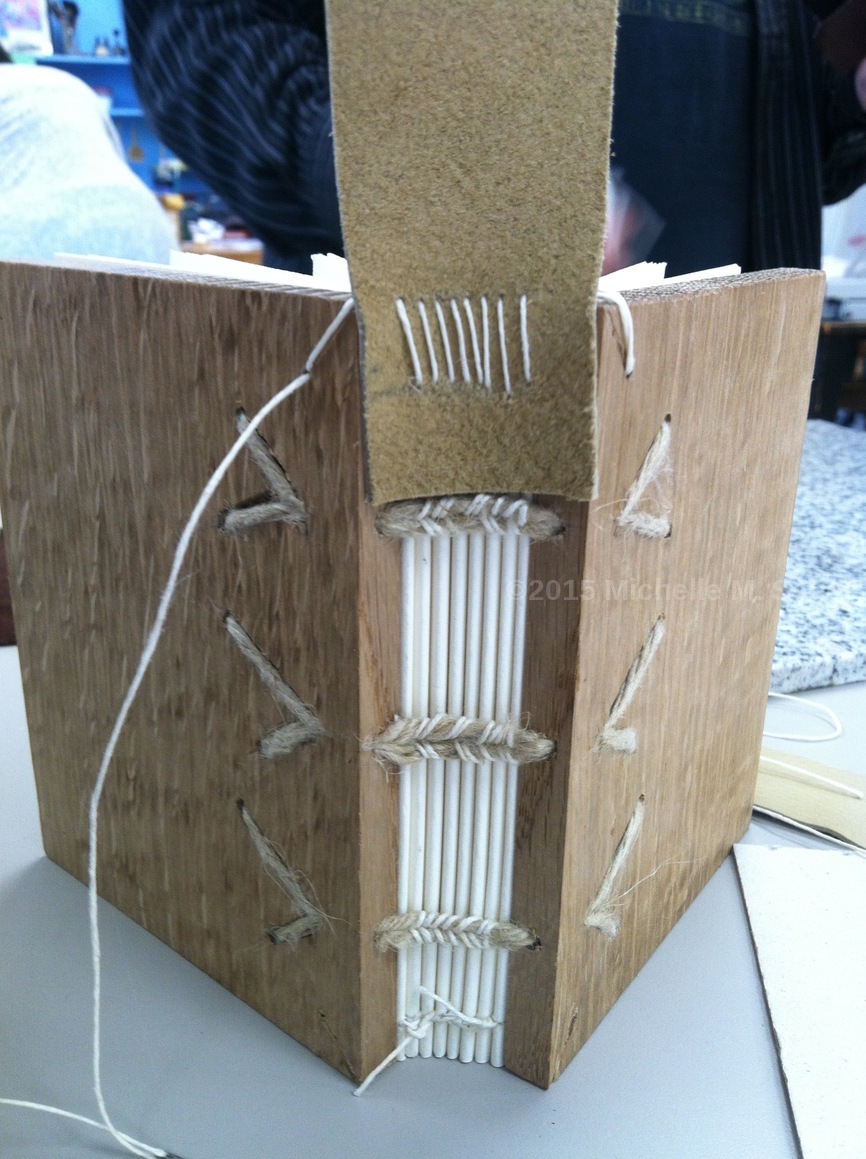

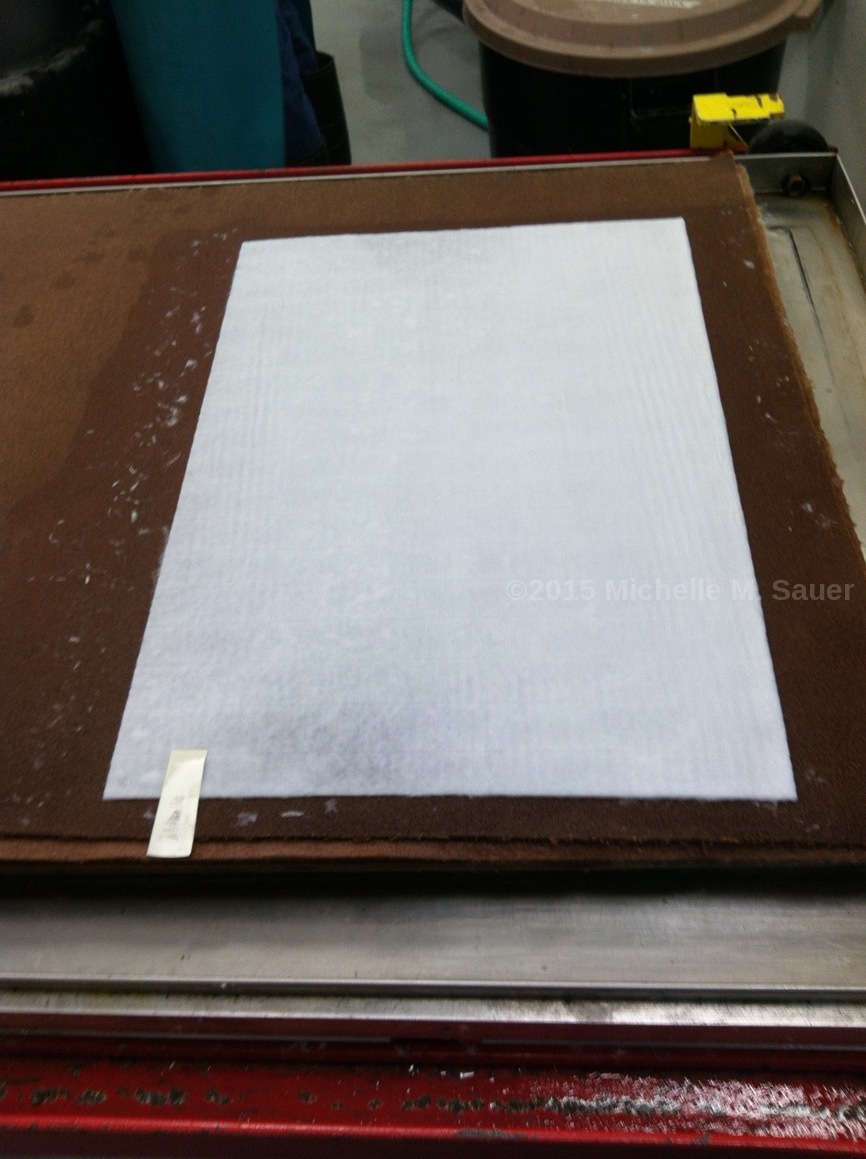

In summer 2015, I was a participant in a National Endowment for the Humanities seminar on Manuscript Materiality. As seminar participants, we experienced first-hand the laborious and delicate work required of medieval scribes to produce the written word. While experimenting with techniques for making parchment, scraping quills, preparing ink, crafting paper, and assembling a sample book, I experienced hapacity in new ways (see images below). My newly-informed appreciation for the physical process of creation has inspired me to rethink the relationships between these texts and the medieval devotional experience, and the centrality of hapacity to devotional literature in particular.

I will consider here readers touching medieval manuscript representations of Christ’s Side Wound. The cult of the Side Wound was widespread throughout the early church, but was superseded by late medieval devotion to the Sacred Heart. Nonetheless, both remained popular throughout the Middle Ages. Early devotions located the wound in Christ’s side; only from the 12th century forward was it understood that Christ’s heart was pierced. (Medieval artistic depictions usually have the opening on the right side of Christ’s body, although anatomically it should be on the left, because the right side traditionally houses goodness.) Christ’s heart became the focus of mystic union. The Side Wound more specifically became a nuptial bedchamber and a refuge, offering protection, nourishment, and cleansing. Womb-like, it also suggested a place of rebirth. In each instance, senses are engaged, especially touch.

Devotional literature often encouraged the faithful to taste, touch, suck, kiss, and enter into Christ’s side wound. Before my NEH seminar, I rarely considered how medieval people touched manuscripts. But, contemporary readers handled them constantly, and, if reading aloud, engaged all the senses in a whole-body experience. The seminar helped me clarify this creative process, and consider scribal intentionality as a deliberate strategy to stage materiality of the manuscript, directing the ways in which readers engaged with the text. It also assisted me in contextualizing the relationship between image(s) and physical text and between image(s) and individual reader. What type of connection was forged between reader and text via the act of touching? How did haptic desire and practice influence the procedures of piety a reader performed?

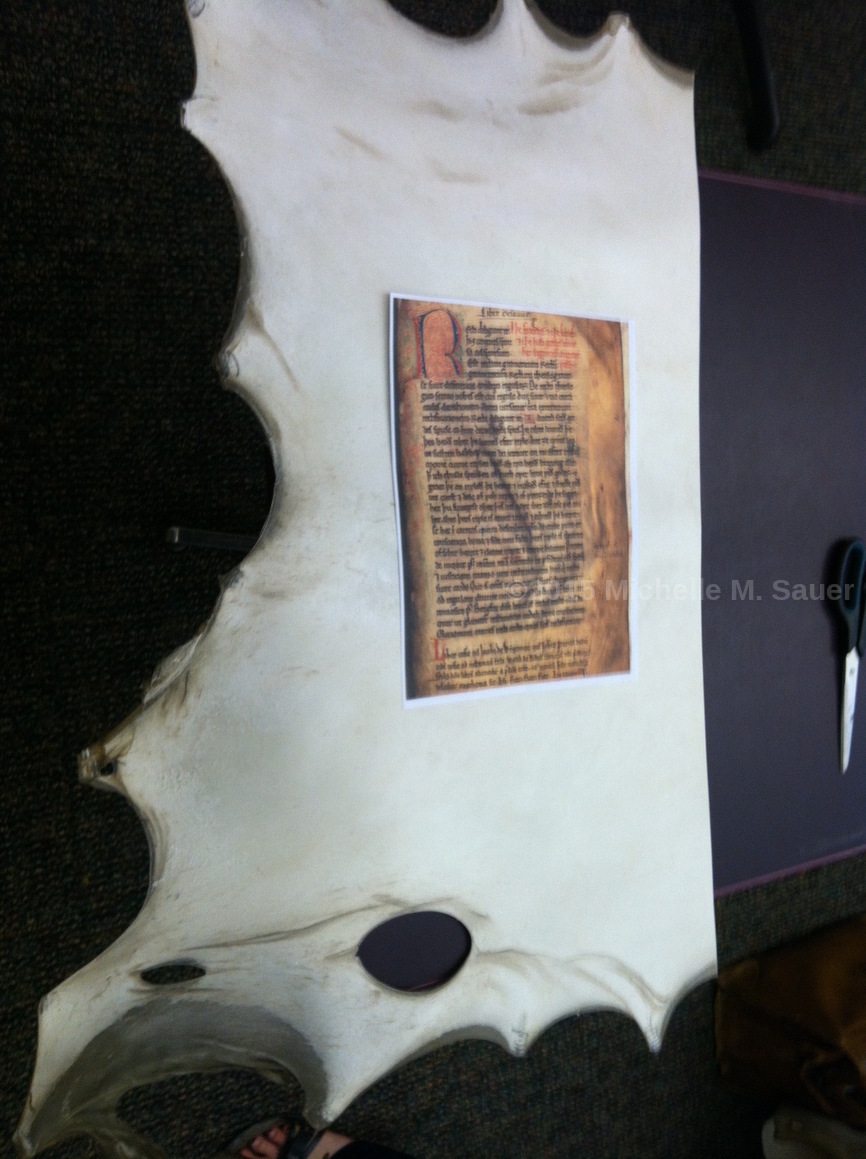

I made vellum. It was challenging. It stank. It killed my arthritic hands. But undertaking this unpleasant process demonstrated how the transformation of skin became essential to medieval haptic perception. Vellum was viewed as having residual energy from the life lived by the animal, and, just like all things, as containing divine essence. Thus, vellum held its own power, activated by the reader’s touch, and lent to any image on its surface. Animal skin could become the medium for divine connection, for religious experience, and for performing piety. Images of Christ, serving as a proxy, allowed the reader physical interaction with his body; images of Christ’s Side Wound facilitated intense affective responses. These tactile exchanges have left the images in some texts scratched, rubbed, and scarred from excessive handling. Portable images and books enabled people to experience divine interactions in the context of personal devotional space. Repeated touching created intimate access; interaction between object and individual resulted in a devotional performance.

Images of the Side Wound were particularly suited for encouraging physical interaction. One remarkable example of this haptic connection is British Library MS Egerton 1821. It is English, dating to around 1490. It begins with three pages, each painted black, on which large drops of red blood trickle down. The third page has been thoroughly worn, perhaps by rubbing. There is no formal image, merely the somewhat abstract representation of suffering and redemption through the blood of Christ.

The upper right portion of folio 2r shows more trauma than the rest, and has, perhaps, been scratched. The points and the squiggles on top of the large drops add to the sensation that the blood is trickling, not static. To the touch, the black painted portions feel smooth. The red drops feel glossy. The worn portions feel rougher and more complex. Of course the manuscript is now 525 years old, but when new, all that black would have left traces behind on the skin. I call this “divine residue.” It would have served as a visual reminder of the physical devotion.

Visual reminders can also be directly useful for salvation. For example, a miscellany produced in 1320 in the Brabant monastery of Villers depicts an isolated, vertical Side Wound surrounded by the arma Christi and an inscription that reads, in part, “This is the measure of the wound in the side of our Lord Jesus Christ.” This points to the tradition of replicating the measurements of Christ’s actual wound. The ‘true measurement’ of the wound was powerful, granting an indulgence to the viewer since it was an ‘exact’ reproduction. The desire for true measurement explains why many Side Wound images appear disproportionately large in comparison to other images on a page: it was done not only to show its prominence, but also in an attempt to depict it to scale, implying an indulgence. Thus, the Villers image implicitly suggests the viewer will receive an indulgence by virtue of its exactness. I made a replica of this Side Wound that I then carried like a textual amulet. When I rubbed it, the parchment became warm to the touch and gave off a faintly earthy scent. The ink (black walnut) left behind “divine residue” on my thumb.

Often Side Wound images in manuscripts show deterioration patterns inconsistent with casual use. For instance, in the Image du Monde (ca. 1320), a Side Wound placed in the center of a folio shows scuffing while illuminations along the edges remain un-abraded. This may indicate the reader intentionally targeted the wound, even without explicit directions to touch it. Such examples of Side Wounds as a sort of contact relic, lending comfort through touch, spill over into other material crafts as well. Beyond the manuscript tradition, we see hand-drawn Side-Wound-shaped seals, which lent credibility to regular legal charters. As well, crystal lozenges and mandorlas were commonly attached to reliquary crosses, designed as metal tokens worn on chains, or fastened to rosaries. This suggests that many craftspeople, not simply bookmakers, encouraged tactile interaction with the Side Wound as a part of everyday piety.

Clearly, tactile and visual perceptions were woven together into the fabric of devotional experience in the Middle Ages alongside reading, with images of the Side Wound serving as a vibrant example of such practices. The production of medieval books certainly involved a great deal of touching: butchering, tanning, scraping, de-hairing, stretching, sanding, writing, sizing, and (potentially) re-doing. But what does it mean to create a book meant to be touched after its creation? One designed to be touched by the scribe or book designer and also the audience? How do words and images interact in these instances? What about material considerations, such as the placement of images on the hair side vs. flesh side? How important is the warmth generated by touch? The scent? These are but a few of the questions we still need to pursue in the study of medieval manuscript materiality.

All photographs by Michelle M. Sauer except Michelle M. Sauer Working on a Sample by Heather Emelia Bain