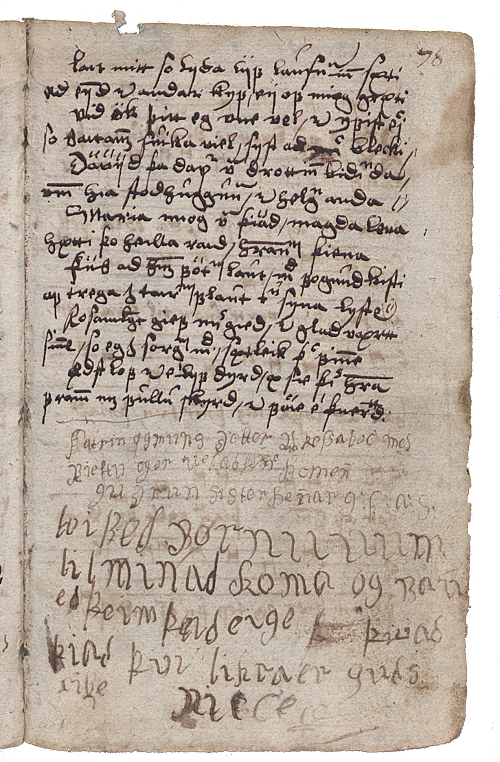

ÍB 65 8vo. A common girl (born 1689) writes in her own hand that she owns this book of hymns. Picture Helgi Bragason, The National library of Iceland.

Though published records have little to say about the bookish activities of secular women in Iceland in the high and late Middle Ages, the limited available evidence confirms that the links between women and books have a long history. The fact that they gifted books to churches and religious houses is the clearest evidence that they owned individual volumes, and perhaps even accumulated modest libraries. Women were educated in the home, normally under the supervision of their mothers, and this remained the case until the nineteenth century. However, evidence suggests that during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries women organised schools in which girls and boys were taught. It seems that initially these children were taught side by side, but that they later went their separate ways when writing instruction began. However, a select number of girls did learn to write, and the fact that such activity attracted written comment confirms that it was a source of interest and admiration. Some girls also learned to count, as can be seen from their skill in calculating the dates of liturgical calendar feasts and the like. That said, female education differed significantly from that available to men; its nature and quality was more dependent on the competence and knowledge of the mother.

Up to the sixteenth century only the daughters of aristocrats and officials learnt to read and even write. During the seventeenth century, however, poor priests’ daughters followed suit, with some achieving knowledge of Latin. The image of the literate working woman also emerged at this time. While Guðbrandur Þorláksson was Bishop of Hólar (1571-1627) he organised the publication of many religious volumes designed to instruct the laity in the new faith. This played its part in promoting literacy among ordinary folk, not least, of course, among priests’ daughters. Around 1700 the spread of literacy was greatly helped when the authorities began to require greater knowledge of Christian doctrine among the population at large.

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century estate inventories show that up to fifteen religious books could be found in the average Icelandic household. Even poor, unmarried working women left a few such volumes behind when they died. The church’s printing house certainly saw to it that the spiritual needs of the laity were met. However, there are few if any extant printed books that were once owned by women during the period from the middle ages to 1730. The chances of such volumes surviving in tact in damp and dingy Icelandic households were slim. We may note that secular printed volumes or manuscripts are rarely mentioned in inventories. Until the removal of the church’s printing monopoly at the end of the eighteenth century such texts circulated mainly in manuscript.

Scholars believe that only a small number of those manuscripts are now extant in the Icelandic national archives, perhaps as few as one in ten. Bearing in mind that little is known about the provenance of many surviving manuscripts, it is surprising that so many of them can be linked to women. The oldest manuscripts owned by women are from the end of the fourteenth and beginning of the fifteenth century. Though few in number they are splendid in appearance. The care and custody of manuscripts improved over time. During the seventeenth century paper became cheaper and the copying of manuscripts flourished under the influence of continental humanism and antiquarianism. Women benefitted from these developments, with a growing number owning two or more volumes that are still extant today.

Initially, ownership of manuscripts was confined to aristocratic women from Iceland’s finest families. Many were connected by ties of kinship. Prominent among them were the wives and daughters of educated men, and they helped to make such volumes available to other women. Bookish mothers and grandmothers also played a key role in promoting book-ownership among their successors. Though we know that women inherited books, it was more often the case that manuscripts were either copied for or gifted to them. As paper became less expensive during the seventeenth century there was an increase in book ownership among the wives and daughters of less wealthy farmers and poor priests. Far from being connected with Iceland’s leading families, several of these new book owners and readers were from modest social backgrounds. Bookish women of this kind become more prominent during the eighteenth century under the influence of Icelandic enlightenment-age thought, with its emphasis on popular education and its legislation on the teaching of reading.

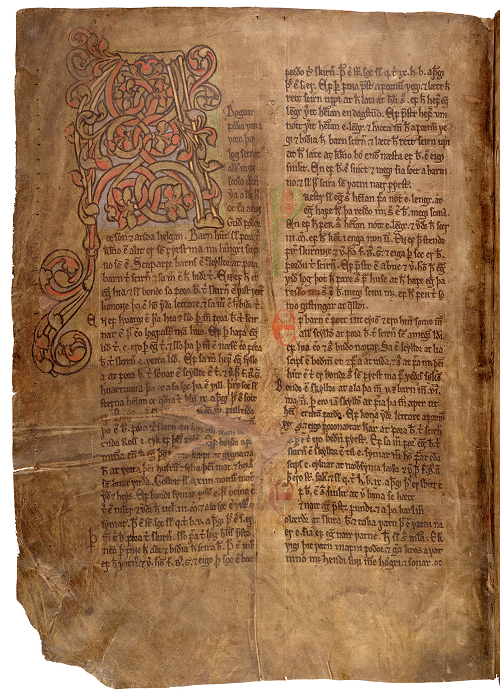

To some extent women’s books reflect one of their principal roles, as mothers and housewives. Until the eighteenth century lawbooks featured prominently on women’s bookshelves. The lawbook (Jónsbók) and the Bible were used to teach children to read. By learning in this way boys were prepared for work in a society whose main official positions were associated with law and theology. And because it was the mother who took responsibility for the primary education of her children, women inevitably learnt to read these volumes themselves.

AM 334 fol, a law book on parchment. Many women owned such books and used them for teaching children how to read. Picture Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir, The Árni Magnússon institute for Icelandic studies.

Miscellanies written for women in the seventeenth and eighteenth century were clearly regarded as handbooks (or, as it were, toolboxes) for housewives, and were probably more often found in their apron pockets than preservation evidence suggests. Such volumes were all written shortly before or after their owners got married. They contain material of use for instructing children, e.g. extracts from Latin School textbooks, riddles, and arithmetical and astrological information. Other material included reminds us that the role of mother and housewife was regarded as far from easy: notes on on gender relations, the Lutheran faith, the calendar, verses about the weather, and any other information that might help protect the household against the forces of evil at work in the world. The home was the major workplace in Icelandic society, and responsibility for the welfare, development and educational attainments of all who lived there lay squarely on the shoulders of the housewife.

From the outset women were eager owners of saga manuscripts, such as the Sagas of Icelanders and the Kings’ Sagas. On the other hand, Árni Magnússon’s diligence as a manuscript collector at the beginning of the eighteenth century left women’s holdings of such volumes much depleted. Although sagas were read for entertainment their educational and utilitarian value was also recognised. Just as is the case in Iceland today the Sagas of Icelanders were part of the school curriculum. Knowledge of Icelandic history was a key element in the education and self-awareness of every Icelander. Saga manuscripts served many purposes for women. In pre-Reformation times—and even afterwards—women owned manuscripts of sagas about the Holy Maidens. Margrétar saga, for example, served as an aid during childbirth, and all extant manuscripts of the saga are thought to have been owned by women, even though specific evidence of this cannot always be found. Legendary Sagas, Chivalric Sagas and chapbooks were popular reading materials for both men and women. Though serving primarily as sources of entertainment, such works offered much civilising counsel. Chivalric tales could teach readers about courtesy and proper behaviour, while many Legendary and Chivalric sagas and chapbooks explore gender relations. By the middle of the eighteenth century it was even considered safe for a well-born young woman to learn to read and write from such stories. Women were every bit as keen as men to learn from old tales how best to cope with life’s vicissitudes.

Before the Reformation Konungs skuggsjá (Kings mirror) and Elucidarius were part of the curriculum at Latin Schools in Iceland. Women certainly owned copies of these works during the sixteenth century and it has been suggested that earlier they may have constituted part of a woman’s dowry. The works’ moral teachings were appropriate for women, and the information about geography and natural history in Konungs skuggsjá would be useful for educating children. Geographical knowledge was important for a woman’s education, irrespective of any child-rearing responsibilities. Konungs skuggsjá also discusses politics and armaments, topics that were of interest to some women. Women could find themselves involved in quarrels and power struggles, and this, as with their role in education, could call for knowledge relating, for example, to the laws operating within Icelandic society. Women would also participate in dinner-table conversations during which topics of all kinds would be discussed. Those same women could have views on matters of social concern, though these might only find expression within the household. Thus, wide-ranging knowledge was important for women not just in their role as mothers but also for their overall self-esteem.

Religious books were commonly owned by women, as they oversaw the spiritual life of their children and, even, of the overall household. Of particular importance were hymnbooks, sermon collections and meditative texts. Such volumes also played a key role in women’s spiritual development. Intended for and popular with a female readership, they were a source of spiritual strength, protection and consolation, and promoted the idea that women were more sympathetic and good-hearted than men. Women’s minds were thought to be more sensitive and empathetic towards those less fortunate. Reading the scriptures would help protect them from the devil’s assaults. Many women sought to live up to the ideal of the pious woman that found fullest expression in the perfect housewife and mother. Others, however, were tireless in their pursuit of wealth and power, though they sometimes sought to hide this from their contemporaries. Women, no less than men, were concerned with their image and if it was in any way compromised on life’s journey they could try to conceal the fact.

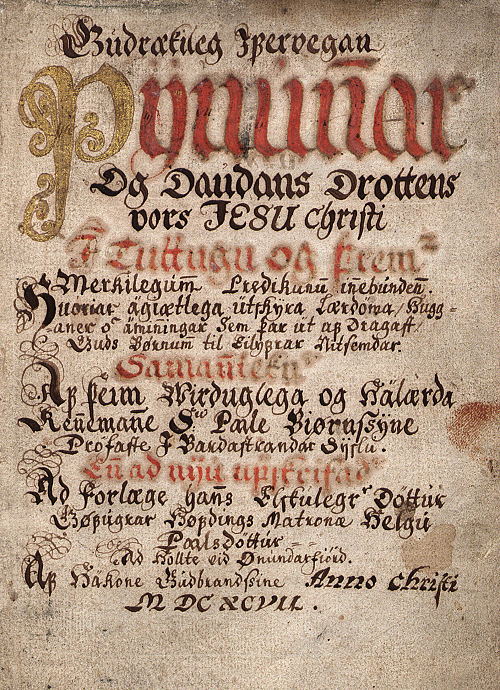

JS 602 4to, a collection of sermons. The manuscript was made for the author‘s daughter. Picture Helgi Bragason, The National library of Iceland.

During the seventeenth century, though women read a broader range of other books than had once been the case, they had a particular fondness for poetry manuscripts. The Reformation saw the arrival in Iceland of new poetic genres and verse forms. The most common books of verse were those whose selected pieces were both religious and secular, serious and light-hearted. After due reverence had been shown to God there was room for levity. The contents of such manuscripts were not always designed to find favour among the ecclesiastical authorities, with some of the poems included mocking foolish menfolk. The rules applying to manuscripts differed from those for printed books, with manuscripts more readily reflecting their owners’ tastes and attitudes. Some manuscripts were regarded as part of the cultural capital of the ruling social order, with the achievements of the family celebrated in verse. It is, however, in miscellanies and poetry books that the image and attitudes of women find fullest expression.

Women put books to a variety of uses. The high-born owned many genealogical volumes; it was very important for an individual’s image and reputation that their aristocratic lineage could be fully authenticated. Accordingly, such books were status symbols. Most volumes, however, served as cultural resources and support for a woman’s principal role as mother and housewife, and their contents certainly reflected social change. At the same time books revealed the education, interests and self-esteem of their owners. Women also looked to them for comfort and protection in an uncertain world. Book ownership was therefore a complex interplay of multiple factors, including education, entertainment, image projection, and cultural capital.

Despite their exclusion from formal Latin School education in Iceland women acquired a good deal of bookish learning. The most important factors for women seeking access to books were ambitious parents and a well-disposed husband.

Guðrún Ingólfsdóttir Ph.D.

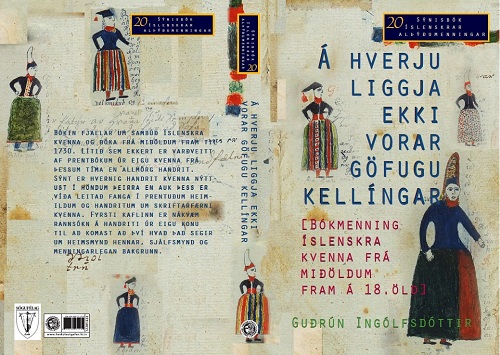

Guðrún Ingólfsdóttir is the author of a new book, The Things our dear old ladies hoard. Icelandic women’s book culture from the middle ages to the 18th century. Her book has been nominated for the Icelandic Literary Prize for academic and non-fiction works.

The book seeks to examine women’s literary culture in Iceland from the Middle Ages up to 1730, i.e. women‘s ability to read and write and how books benefitted women. The best way to gain insight into women‘s education, role, world view and self-esteem is to examine their books. The present volume does not aim to present an overall picture of women’s lives in Iceland, not least because relevant sources for the period between the Middle Ages and 1730 are often relatively sparse. However, full use has been made of available documentary evidence in order to better understand the role of women in Icelandic book culture. There are, for example, funeral eulogies about a small number of women in which female morality and piety is invariably valorised. There are also commemorative verses and elegies that contain important information also found in biographical accounts but the latter are much less common. The yearbooks of Jón Espólín, Iceland’s first “gossip columnist”, were another irresistible source of information. In examining these sources the overriding priority was to provide these women with a voice by allowing their books to speak to us. Indeed, the present study draws on the traditional notion of the book as a mirror, in which a man can observe himself, both as he is and as he ought to be. Here, however, the focus is on the image of women as reflected in their books; we learn of their world-view and preoccupations, and the role that books played in their lives. The first chapter examines the manuscripts of one common woman, thereby allowing the voice of such individuals full expression alongside the aristocratic women.