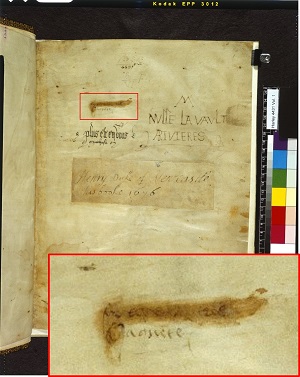

Personal motto and signature of Jacquetta of Luxembourg, British Library MS Harley 4431, f. 1r Copyright British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts

On the opening page of British Library Harley 4431, a collected works of Christine de Pizan, there is a small inscription. If you look only once you are likely to miss it – the inscription is dwarfed by the other markings on the page and an attempt has been made, at some point in the manuscript’s history, to erase it altogether. The obscured inscription is the name of a woman – ‘Jaquete’ accompanied by a short phrase – ‘sur tous autres’ (above all others), perhaps a personal motto.

When I first saw this signature, I felt as if I had struck gold. Here was evidence of a female reader engaging with the work of a great woman writer, Christine de Pizan. But as my elation subsided, I began to wonder – what exactly did the inscription mean? Should I interpret it as a mark of ownership as does the British Library catalogue? Did a signature on an opening flyleaf necessarily imply that the person who possessed the book also read the book?

Tracking down a medieval female reader can often feel like a treasure hunt. The persistent researcher/detective must collect small scraps of evidence, decide how to interpret these clues, and then carefully piece them together. Evidence for readership comes in many forms. Book ownership is sometimes indicated in wills, inventories, registers, household accounts, and medieval library catalogues. For example, in a detailed will prepared in 1498, Anne Wingfield Harling, an East Anglian gentlewoman, bequeaths “A French booke called the Pistill Othia” to “my lord Surrey.” The book in question is almost certainly Christine de Pizan’s The Letter of Othea (1399), a knightly conduct book. Similarly, as Carol Meale has noted, we catch a glimpse of Alice Chaucer’s reading interests in an inventory of goods transferred to her family estate in 1466. The document lists seven literary manuscripts including a “french boke of le Citee de dames” and “a french boke of temps pastoure,” quite possibly Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) and The Book of the Shepardess (1403).

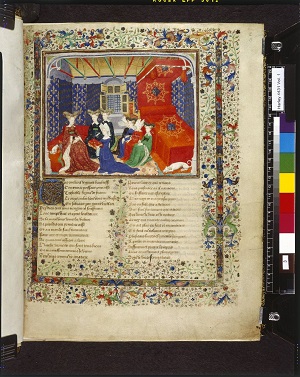

Another source of information on medieval readership comes in the form of dedications to specific patrons. Sometimes these dedications are tantalizingly vague, as when the writer Stephen Scrope addresses an unnamed “high princess” in the prologue to his translation of Christine de Pizan’s The Letter of Othea. Other dedications are more specific. For example, the manuscript noted above, Harley 4431, opens with a “prologue addressed to the queen” (Prologue adreçant a la royne) in which the author, Christine de Pizan, dedicates her collected works to Isabel of Bavaria, Queen of France. The act of dedication is shown in a beautiful illustration at the beginning of the manuscript in which a group of aristocratic women gather as Christine gives the large manuscript to the Queen.

Christine de Pizan presents her collected works to Isabel of Bavaria, British Library Harley MS 4431, f. 3r Copyright British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts

Finally we come to the type of evidence that seems most immediate and concrete – the appearance of physical marks left by readers in extant medieval manuscripts. Like other clues to readership, however, these marks vary in clarity and meaning. A manicule, check mark, or X might point to a particular passage of text but leave no information about the reader’s identity. Or a name inscribed on a flyleaf may tell us who owned the book but not whether he or she took an interest in a particular section of text. In many cases it is difficult to differentiate ownership of a book from engagement with the text.

On some rare occasions a connection between flyleaf and marginal annotations may provide evidence that an individual owned a medieval book and read its contents. Such is the case for ‘Jaquete,’ the female reader of Harley 4431. Not only does her name appear on the opening page of the manuscript, it is also inscribed in the margins of three additional pages, suggesting that she read the Christine de Pizan texts enclosed within the covers of her beautiful book.

But who was ‘Jaquete’ and how did she come to possess the book? Here the researcher/detective must pull out the tools of biography and book history to illuminate the name left on the page of the manuscript.

The signature in Harley 4431 has been identified as the hand of Jacquetta of Luxembourg, the Duchess of Bedford from 1433 to 1472, and, according to several medieval writers and one modern novelist – a dangerous sorceress. Jacquetta arrived in England in 1433 at the age of seventeen, having left her home in present-day Belgium to become the wife of a powerful English nobleman. Her new husband, John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, was the brother of King Henry V and had been named the Regent of France in 1422. The Duke’s marriage to Jacquetta was intended to bolster the alliance between England and the Dukes of Burgundy during the Hundred Years War with France.

Though initially used as a passive pawn to secure foreign support, Jacquetta quickly became a political player in her own right. Described by a contemporary chronicler as “lively, beautiful, and gracious,” Jacquetta wasted no time integrating herself into the royal court of her new home (La chronique d’Enguerran de Monstrelet, vol. 5, p.55). Within a month of arriving in England, Jacquetta became an English citizen, and less than a year later, she was given the robes of the Order of the Garter. Although her husband died only 18 months after their marriage, Jacquetta chose to remain in her adoptive home and continued to style herself the Duchess of Bedford for the rest of her life.

Perhaps in an effort to remain powerful and autonomous, Jacquetta chose as her second husband not a Duke but a lowly knight named Richard Woodville. The marriage was contracted through Jacquetta’s “own free will” and was loudly lamented by her relatives who believed Richard to be “inferior to her first husband and to herself in regard to birth” (La chronique d’Enguerran de Monstrelet, vol. 5, p. 272).

In 1463, some 25 years after her controversial marriage to Richard Woodville, Jacquetta engineered another unexpected union – this time between her eldest daughter, Elizabeth Woodville, and the new king of England, Edward IV. This successful political maneuver, termed witchcraft by several medieval chroniclers, propelled the Woodville family to a position of high favor and influence at the English court (For further details on Jacquetta see the work of historian Lucia Diaz Pascual).

Elizabeth Woodville, Queen Consort of Edward IV of England, c. 1471, Queen’s College, Cambridge, Portrait 88 Public Domain (Wikipedia Commons)

Jacquetta’s social ascension and political triumph accord well with the inscription she left on the opening page of Harley 4431 – ‘above all others.’ Did the book itself play a role in Jacquetta’s social and political success?

As noted above, the lavish manuscript was originally owned by the queen of France, Isabel of Bavaria. However, less than ten years after Christine gave the book to the queen, it passed into the hands of Jacquetta’s first husband, the Duke of Bedford, who purchased the Louvre library upon becoming the Regent of France in 1422. The book came to Jacquetta, as either a marriage gift or an inheritance in Bedford’s will, between 1433 and 1435.

Jacquetta was no doubt aware of the French-royal provenance of the manuscript and the political meaning encoded in its passage to England. The book was a superb example of the artistic and literary French culture over which the English sought dominance. That a duchess living in England had come to possess a book intended for a French queen was likely seen as an English triumph. Did Jacquetta use this cultural capital to advance her social prestige in England? Did she perhaps share the impressive continental book at social gatherings or display it continuously on a lectern at her London residence? Jacquetta’s ownership of Harley 4431 would have reinforced her status as the widow of the great Duke of Bedford and would have helped to declare her commitment to English efforts during the Hundred Years’ War.

Through a combination of archival evidence, biographical research, book history, and literary-historical analysis, the obscured female name on the opening page of Harley 4431 becomes the site of an exciting story. While reconstructing the lives and reading habits of medieval women can sometimes feel like working on a complex jigsaw puzzle, through the use of multiple scholarly methods we can begin to piece together a more complete picture of women’s literary practice in the Middle Ages.

Sarah Wilma Watson