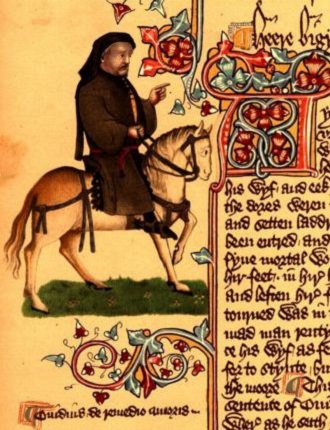

Chaucer, Ellesmere Manuscript. Image from Wikimedia Commons

My most recent book project, entitled Chaucer and Religious Controversies from the Middle Ages to the Augustan Age, adopts the comparative, boundary crossing approach that generally characterizes my research. In this project, however, I shift my attention from texts and figures that are, by and large, relatively unknown to one of the most canonical of literary figures, Geoffrey Chaucer. The idea that Chaucer is an international writer raises no eyebrows. Scholars have long elucidated vital connections between Chaucer’s work and that of French and Italian writers including Machaut and Boccaccio. Similarly, a claim that Chaucer’s writings participate in English confessional controversies in his own day and afterward provokes no surprise. Indeed, Chaucer’s ecclesiastical satires and critiques in the Canterbury Tales were so well known that Protestant reformers adopted him as one of their own after Henry VIII broke with Rome. Relatively little work has been done, however, considering Chaucer’s Continental interests and influences as they inform his engagement with religious cultures and his production of religious writings. Likewise, while the early modern “Protestant Chaucer” is a familiar figure, Protestant claims to the Chaucerian legacy were not uncontested, though the early modern “Catholic Chaucer” has not received much attention. Writing my two previous books convinced me of the vital importance both of adopting an international perspective in studying the religious and textual cultures of England and of rethinking conventional demarcations of historical periods. Thus, this book seeks to fill gaps in Chaucer scholarship by situating Chaucer and the Chaucerian tradition in an international textual environment of religious controversy spanning four centuries.

Chapters in this book address such topics as Chaucer’s female monastic pilgrims and the complex hybridity of later fourteenth-century English religious culture, in which innovative yet orthodox trends in female spirituality from the Continent blended with trends characteristic of the emergent Lollard movement; the place of Chaucer in Catholic contributions to the so-called “Stillingfleet Controversy” sparked by Serenus Cressy’s publication of Julian of Norwich’s revelations as well as in Dryden’s near-contemporary publication of his Fables Ancient and Modern, which he wrote after his conversion to Catholicism; and the use of the Chaucer tradition by the colonial American writers Cotton Mather, Anne Bradstreet, and Nathaniel Ward. Two chapters, though, are particularly relevant to the Women’s Literary Culture and the Medieval Canon project and have been the subjects of my presentations at the Leverhulme Network events at Chawton House in 2015 and in Boston in 2016.

In the second chapter of Chaucer and Religious Controversies, which follows my analysis in chapter 1 of Chaucer’s female monastic pilgrims, I consider manuscripts containing texts by Chaucer and texts in the Chaucer tradition found in the later medieval and early modern libraries of Denney, Syon, and Amesbury. I explore what reading such texts may have meant to the nuns in these communities, since the fact that nuns from these houses inscribed their names in the manuscripts containing Chaucerian texts suggests women religious actually were reading them. The Chaucerian material available to the nuns of Denney fits squarely within the expected parameters of later medieval and early modern monastic women’s devotional reading. This community most likely owned MS BL Arundel 327, a complete text of Bokenham’s Legendys of Hooly Wummen. This mid-fifteenth-century manuscript, probably produced for Thomas Burgh to give to the nunnery, bears a scribal notation indicating it was “doon wrytyn in Canebryge by his sone Frere Thomas Burgh, in the yere of our lord a thousand foure hundryth seuyn and fourty, whose expence dreu thretty schyligyns, and yafe yt on to this holy place of nunnys that þei shulde have mynd on hym and of hys systyr dame Betrice Burgh; of þe wych soulys Jhesu have mercy. Amen (f. 193).” Bokenham’s Legendys of Hooly Wummen features Chaucer prominently; Bokenham on more than one occasion invokes Chaucer as a master of the English vernacular, as an authoritative predecessor poet. For instance, in a classic use of the humility topos, Bokenham writes:

But sekyr I lakke bothe eloquens

And kunnyng swych maters to dilate,

For I dewllyd neuyere wyth the fresh rethoryens,

Gower, Chaucers, ner wyth lytgate…. (lines 414-17)

The nuns of Denney accordingly encounter the figure of Chaucer in MS Arundel 327 as a great English poet in the context of religious material one would readily expect to find in a nunnery library.

Farmhouse converted from the former Denney Abbey. Wikimedia Commons, photograph by Rob Enwiki

My focus in this chapter is primarily on the communities of Syon and Amesbury rather than on Denney, however, since Chaucerian texts found in the libraries of Syon and Amesbury comprise potentially more surprising reading material for nuns than the contents of Arundel 327. The texts by and featuring Chaucer found in the Syon and Amesbury libraries are not saints’ lives or other conventional devotional texts (like Lydgate’s Life of Our Lady, which contains ample praise for Chaucer but of which no records survive indicating possession by an English nunnery). Rather, the Chaucerian material found in the libraries of Syon and Amesbury concerns courtly and political subjects.

Oxford, Bodleian Library Laud misc. 416 is one manuscript filled with courtly, politically oriented Chaucerian material that was owned by the Brigittine nuns of Syon. Laud misc. 416 is a compilation that as a whole emphasizes the socio-political with a focus on the common profit. One of the texts included in the compilation is John Lydgate’s Siege of Thebes. The Siege, a text framed as an addition to the Canterbury Tales presenting the Theban backstory to the Knight’s Tale, is, as Derek Pearsall’s asserts, perhaps Lydgate’s most political poem. Lydgate’s Siege is preceded in Laud misc. 416 by part two of Peter Idley’s Instructions to His Son, which draws upon John Lydgate’s Fall of Princes. In fact, the “Fall of Princes is…a supplementary source” to Robert Mannyng’s Handlyng Synne in Book II of the Instructions. According to Charlotte D’Evelyn, from the Fall of Princes “Idley has taken undisguisedly forty-six stanzas…. Nearly all of the forty-six stanzas are incorporated with only slight changes, many lines with no change at all” (p.49). Following the Siege is Lydgate and Benet Burgh’s Secrets of Old Philosophers, a text that, as Charles F. Briggs notes, purports to be a letter from Aristotle to Alexander the Great covering topics “from ethical and political advice, to prescriptions for diet and hygiene, to astrological lore” (p.21) Laud misc. 416 additionally includes the universal history Cursor mundi and an English prose translation of Vegetius’s treatise, De re militari, which Catherine Nall describes as “perhaps the most authoritative military manual of the Middle Ages” (p.11). The final text in the manuscript is Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls, an imperfect version consisting only of lines 1-142. This portion of the Parliament readily fits the thematic concerns of the other texts in the manuscript, since lines 1-142 of the Parliament concern themselves primarily with a synopsis of Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis, which is the final part of his De re publica. M. C. Seymour indicates that at least eight folios are “lost after f.289,” so Laud misc. 416 most likely originally contained the full text of the Parliament of Fowls (p.25).

The Amesbury nuns too had opportunity to encounter Chaucer in a manuscript context that emphasizes the courtly and the political rather than the overtly devotional. Like Laud misc. 416, BL Add. 18632 is a mid-fifteenth-century manuscript, and it bears a sixteenth-century Latin inscription indicating that it was presented to the prioress and convent of Amesbury by “Richardus Wygyngton, capellanus” in 1508. The full inscription reads: “Istum librum dominus Richardus Wygyngton, capellanus, dedit prioresse et conuenti monasterii Ambrosii Burgi in vigilia natiuitatis beate Marie uirginis Anno Domini m<illesim>o quingentesimo octaua, ut ipse ex caritate orent pro ipso et amicis suis. Et si aliquis istum librum a monasterio alienauerit, anathema sit” (fol. 99v ; quoted by David Bell, p.104). Interestingly, “The fly-leaves of this manuscript (fols. 2 and 101) contain fragments of the household accounts of Elizabeth de Burgh, countess of Ulster. The accounts cover parts of the years 1356-9 and are of interest in mentioning payments made to Geoffrey Chaucer when he was a page in her household” (Bell, p.103). So here is Chaucer triply present in a monastic library—a manuscript containing two texts in which the figure of Chaucer appears is bound with accounts in which Chaucer also features. Also like the materials in Laud misc. 416, the contents of Add. 18632 are not as clearly applicable to the situation of female monastic readers as are female saints’ lives of Arundel 327. In this manuscript, a copy of Lydgate’s Siege of Thebes is accompanied by Thomas Hoccleve’s Regiment of Princes, his speculum princeps that gives pride of place to the figure of Chaucer.

Amesbury (Church of St Mary & St Melor). Wikimedia Commons, photograph by Chris Talbot

What the significances of such texts were for women religious, and how nuns engaged with these texts within and outside their monastic communities, are what occupy me in this chapter of Chaucer and Religious Controversies. As I discuss, the nuns of Syon and Amesbury were positioned to draw upon these texts to develop rhetorical strategies and courses of action in complex political situations, and these texts played important roles in the sophisticated devotional cultures of these monastic communities. As I argue in chapter 1, Chaucer’s Second Nun’s Prologue and Tale represent a sophisticated engagement with contemporary, and controversial, overlapping debates concerning Continental female spirituality and heterodox English religious thought, debates addressing female religious authority, vernacular theology, and religio-political reforms. The female monastic communities in which Chaucer’s manuscripts were located were communities in which the Second Nun might have felt right at home; they were communities at once committed to vibrant vernacular textual cultures, devotional and theological innovation, and political engagement. And, just as the Second Nun’s St. Cecelia offers “conseil” to her husband and instruction to Tiburce, Maximinus, and Almachius, the monastic communities of Syon and Amesbury had interests in the provision of religious as well as political instruction, enterprises for which the Chaucerian works in their libraries were well suited.

The chapter that follows this one in Chaucer and Religious Controversies is also relevant to the work of the Women’s Literary Culture and the Medieval Canon project. Chapter 3 concentrates on texts from the 1550s through the 1580s in which a Catholic strand of Chaucer reception develops to counter the dominant early modern reception of Chaucer as a proto-Protestant, as a “right Wyclevvian” as John Foxe calls him in the Acts and Monuments. Among the texts representing this Catholic tradition are William Forrest’s History of Grisild the Second (1558) along with other religious writings that he produced in a manuscript (BL Harley 1703) on which he worked possibly into the early 1580s. William Forrest was a royal chaplain to Queen Mary, and he presented the History of Grisild the Second to her in 1558. Prior to this royal service, he had been at Oxford in 1530, when Henry VIII sent to the university to procure a judgement in favor of his proposal to divorce Katherine of Aragon. Forrest was also present at Katherine of Aragon’s funeral at Peterborough in 1536, so he was an eyewitness to arguments and events he brings into his reworking of the Griselda story. In Forrest’s writings, the interplay of gender, authority, female devotion, and women’s religious speech—questions that preoccupy Chaucer’s treatments of women religious and inform English monastic women’s engagements with Chaucer and the Chaucer tradition—remain prominent. A nexus of overlapping debates about literary canon formation, the nature of the true English church, and competing representations of English dynastic histories that are central to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century texts treated in the final two chapters of this book also emerge perceptibly in Forrest’s engagements with Chaucer and the Chaucer tradition in the second half of the sixteenth century.

While in chapter 2, I explore ways in which actual later medieval and early modern monastic women engage with texts by Chaucer and in the Chaucer tradition dealing with such topics as good government and right rule, in my analysis of William Forrest’s writings, I examine a different configuration of the intersection of gendered political authority, Chaucer’s writings, and the provision of royal advice. In this age of female rule, also an age in which Catholicism was strongly associated with transgressive femininity by Protestant reformers and polemicists, as Forrest ponders questions of royal and religious authority and considers how rulers should be advised, he turns to a different part of the Chaucerian corpus than those which occupied the female monastic readers considered in chapter 2. Forrest turns instead to the Clerk’s Tale, retelling the story of Griselda and Walter with the starring roles played by Katherine of Aragon and Henry VIII, and he associates Chaucer with a type of Marian piety and forms of female devotion in some ways quite different from those found in the Second Nun’s Prologue and in the Prioress’s Prologue and Tale.

Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale helps Forrest to reanimate a Catholic, medieval past that was an age of female virtue and Catholic religious devotion. In chapter 3 my 2005 book Women of God and Arms, I argue that later medieval and early modern writers often adopted a strategy of “cloistering” such politically engaged women writers as Christine de Pizan and such politically active women as Isabel of Castile, mother of Katherine of Aragon. In many respects, Forrest’s History of Grisild the Second represents another iteration of this strategy, one that draws upon the authority of Chaucer to advocate a feminine, Catholic, nonthreatening mode of queenship. Thomas Betteridge contrasts Forrest’s vision of Mary with that of John Heywood in The spider and the fly, saying that while Heywood’s Mary “sweeps away the past and restores order, there is a sense in which Forrest’s Mary is being sucked back into the past” (Betteridge, “Maids and Wives,” LOC 3179). I would add, she is being “sucked” into a particular interpretation of the past—the medieval, Catholic past envisioned as an age of “cloistered” women who are chaste, passive, silent on matters of religious controversy and political conflict, obedient to male authority figures, and whose lives center on traditional devotional practices of prayer, contemplation, and good works. That Catholic, medieval past continued to live in Katherine of Aragon embodied as Griselda in the History, and Forrest means by his presentation of her exemplary life to ensure it is revived in Mary and perpetuated in the lives of the offspring he hopes she will have.

Forrest’s prescriptions for female virtue and ideal queenship minimize possibilities for women’s activities in the religio-political spheres, particularly the sorts of didactic, autonomous activity represented by the Second Nun and her St. Cecelia or by the nuns of Syon and Amesbury. In the History of Grisild the Second, and elsewhere in Forrest’s writings, the preservation of English religious orthodoxy, which is Roman Catholic orthodoxy, and the assurance of the proper government of the realm depend on the maintenance of these modes of female conduct and female devotion. As he will do for Dryden and the Catholic controversialists whom I discuss in chapter 4, “Father Chaucer” proves quite useful in Forrest’s efforts to mobilize yet manage medieval legacies and to assert fairly narrowly constrained roles for women in religious and political affairs. As I argue in the final chapter, though, the active, vocal, didactic women of the Chaucerian tradition like the Second Nun and the Wife of Bath do not disappear from the scene, and will come to have a role of their own to play in the writings of the New England poet Anne Bradstreet, who participated in the confessional controversies of her day.

Professor Nancy Bradley Warren