The martyrdom of St. Cecilia of Rome and St. Valerian. Detail from a late fifteenth-century Book of Hours. The Hague, KB, 76 F 2. fol. 277r . Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum & Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag. Bron: manuscripts.kb.nl

In the 1380s, a woman has just begun to tell her story, when she remembers another narrative, heard in her teens: “I harde a man telle of halye kyrke of the storye of Sainte Cecille, in the whilke shewinge I understonde that she hadde thre woundes with a swerde in the nekke, with the whilke she pinede to the dede’ (Vis. 1.36-38, ed. Watson and Jenkins). [‘I heard a man of Holy Church tell the story of Saint Cecilia, from which account I understood that she had three wounds in the neck from a sword, through which she suffered death.’] (Trans. Barry Windeatt, Revelations of Divine Love, p. 4). After describing the wish for three spiritual wounds which this legend inspired, Julian of Norwich begins to capture the visions she claims to have received later, at thirty and a half. Interestingly, in the resulting text, A Vision Showed to A Devout Woman, she refers to her visions and to the legend with the same literary term, “shewing”, which means both “account” and “revelation”. The visions and the text, then, share the legend’s narrative character.

When the visionary experience is told once more years later in A Revelation of Love, Saint Cecilia and the preacher are nowhere to be found. Instead, the text brims over with numerous brief exempla by God and the narrator. In addition, the narrator more frequently draws her listener’s or reader’s attention to her own storytelling. When doing so, A Revelation uses terms also found in other texts that reflect upon their own writing and interpreting. However, unlike these other texts, A Revelation employs these terms also to describe Christ’s mothering.

In this post, I will examine Julian’s blend of poetics and theology, reading the texts through the literary lens they themselves offer. The literary concepts of A Revelation, I argue, exploit the maternal and physical associations of the vernacular to bring to life its central motif of Christ’s motherhood. Julian’s poetics thus incarnates her theology. Ultimately, I will illuminate how A Revelation thus engages with contemporary discussions and worries about whether the vernacular could represent God’s Word.

Heart-Shaped Winged Altarpiece (Colditz Altarpiece). by Lucas Cranach the Younger, 1584. Painting on limewood. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg. Image: Wikimedia.

Building on Holy Ground

To begin with, the literary terms in A Revelation invite the reader to see parallels between Julian’s narratorial activity and Christ’s maternal activities. For example, when clustering the different visionary moments into revelations in her later text, Julian characterizes the First Revelation as showing “the strengthe and grounde of alle” (Rev. 6.55), “the strength and foundation” of the Revelations that follow. “Grounde” also denotes a Biblical passage for exposition; Julian has indeed just been expounding the Revelation. The other Revelations, then, build upon and gloss the first one.

In her famous meditation on Christ’s motherhood, which cross-references the First Revelation, the same concept returns in a passage that deftly blends gynaecological imagery and storytelling metaphors:

“Oure kinde mother […] he woulde alle holy become our moder in alle thing, he toke the grounde of his werkes fulle lowe and mildely in the maidens womb. And that he shewde in the furst, wher he brought that meke maiden before the eye of my understanding. (Rev. 60. 5-8).

[Our mother in nature […] because he wanted to become our mother wholly and in all things—undertook the foundation of his work very humbly and very gently in the Virgin’s womb. And that he showed in the first revelation where he brought that meek maiden before my mind’s eye[.]] (129)

This description not only provides “grounde” with gynaecological and material resonances by referring to Mary’s womb and by alluding –by means of Christ’s downward movement- to the earlier Parable of the Lord and Servant, in which Christ “fell …into the slade [hollow] of the maidens wombe” (Rev. 50.189). It also sends the reader back to the “grounde” of the whole text, the First Revelation.

Furthermore, by incarnating himself, Christ begins his “werke,” a term that could also refer to a literary composition. The passage thus parallels Christ’s “werke” and Julian’s “werke”. Julian comments upon the First Revelation with her reflections and other visions, her whole “werke”; similarly, Christ’s conception forms the text explained by Christ’s motherhood, his whole “werke”. In this way, Julian’s expanding of one narrative segment in the vernacular into several becomes an image of Christ’s giving birth to himself.

Vierge Ouvrante. Sixteenth-century. L’église Saint-Sébastien de Palau-del-Vidre. Palau-del-Vidre, France. Photograph by the author.

A Vierge Ouvrante of Words

While creating these parallels, A Revelation often gives the literary terms more physical and maternal overtones. It thus cleverly draws upon the associations between the vernacular and the bodily which contemporary derogatory thought about Middle English saw as limiting its capacity to inscribe the sacred. The previous citation already showed a concept becoming something bodily, a womb, and material, a hollow and ground; Julian’s use of the term “mater”, blurring the distinction between such stuff the body is made on and such stuff texts are made on, is another example of her incarnating poetics.

Other storytellers also frequently speak of their text as having “mater”, “content” or “subject matter”. Chaucer’s Parson for instance promises his fellow pilgrims that his tale offers “moralitee and vertuous mateere” (“The Parson’s Prologue”, l. 38). In the proclamation to the Croxton Play of the Sacrament the narrator calls out to the audience that “We be ful purposed with hart and thowght/off our mater to tell the entent” [“we fully intend with heart and thought/ to tell the import of our subject matter”].

A Revelation, in a passage not found in A Vision, weds this sense to the sense “physical substance”:

Whan God shulde make mannes body, he toke the slime of the erth, which is a mater medeled and gadered of all bodely thinges, and thereof he made mannes body […] In this endlesse love, mannis soule is kept hole, as all the mater of the revelation meneth and sheweth (Rev. 53. 35-38, 40-42).

[ [W]hen God was to make man’s body he took the slime of the earth, which is matter mixed and gathered from all bodily things, and from that he made man’s body […] And in this endless love man’s soul is kept whole, as the subject matter of the revelations means and shows]. (119)

The matter of mud, the human body and the text can all be shaped and gathered into a signifying whole. With its emphasis on embodiment, this reflection firmly grounds the literary term in the tangible and the physical: it becomes as bodily as critics of vernacular religious writings considered the vernacular and the lay mind. Yet this very stuff-ness signifies that God holds together the text like He made and holds together human body and soul. The emphasis on materiality also gives both God’s making and Julian’s maternal overtones: after all, the mother was thought to contribute the matter of the foetus.

Furthermore, turning the materiality of the literary terms up to eleven allows Julian to turn the text as an artefact into an instrument that Christ needs to for his daily mothering. For instance, countless cross-references are strewn throughout A Revelation, to a far greater extent than in A Vision. These cross-references create the loving wrapping (“wrappeth us and windeth us,” Rev. 5.3,4) in divine goodness which Julian ascribes to mother Christ.

In a passage in the Fifteenth Revelation that anticipates the meditation on Christ’s motherhood, the narrator both describes and creates circular structures:

And oure savioure is oure very moder, in whome we be endlesly borne and never shall come out of him. Plenteously, fully and swetely was this shewde; and it is spoken of in the furst, wher it saide: ‘We be all in him beclosed.’ And he is beclosed in us; and that is spoken of in the sixteenth shewing, where he seyth: ‘He sitteth in oure soule.’ For it is his liking to reigne in oure understanding blissefully. (Rev. 57. 42 -46)

[Abundantly, and fully, and sweetly was this shown; and it is spoken of in the first revelation, where he says ‘we are all enclosed in him and.’ And he is enclosed in us; and it is spoken of in the sixteenth revelation, where it says ‘he sits in our soul’; for it is his pleasure to reign blissfully in our understanding, and to sit restfully in our soul.] (126)

The passage first encourages the reader first to go backward—mentally, or by turning the page—from the Fifteenth Revelation to the “furst […] shewing”. The reader is then invited to move forward to the last and Sixteenth Revelation, and then necessarily needs to return to the Fifteenth Revelation. The reader, then, becomes as textually enclosed in A Revelation as he or she is spiritually enclosed in God.

Yet this wrapping can only be achieved because of the material overtones of the vernacular terms and the materiality of the artefact; it is A Revelation’s wrapping the reader in the tissue of words and the vellum of the work that enables Christ to wrap humanity maternally and eternally in his divine, skin-like matter, like a Vierge Ouvrante. Julian’s storytelling thus not only mirrors Christ’s parenting, but also makes an indispensable contribution to it.

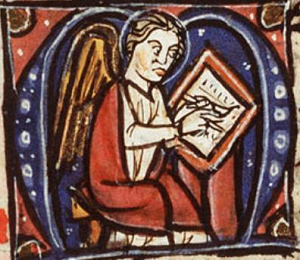

The symbol of the Evangelist St. Matthew: the angel, writing. Detail from a thirteenth-century French Book of Hours. The Hague, KB, 132 F 21 fol. 484v. Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum & Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag. Bron: manuscripts.kb.nl

Ignoring Her Own Advice?

However, A Revelation also seems to pick its literary concepts apart. That is, those reading or hearing her text may have been puzzled by how her text sometimes contradicts its own poetics. For example, in both A Vision and A Revelation, Julian ponders about free will and providence, in A Revelation to an even greater extent than in A Vision. Inspired by a vision of God at the centre of all things, she asserts in A Vision (8.13, 14) “Nor nathinge es done be happe ne be aventure, botte be the endeles forluke of the wisdom of God,” adding in A Revelation, “if it be happe or aventure in the sight of man, our blindhede and our unforsight is the cause.” (11.5-7). [“Nothing is done by chance or accident but by the eternal providence of God’s wisdom.” “If it seems to be chance or accident in our eyes, our blindness or lack of foresight is the cause.”] (11, 55) “Aventure” refers to accident or chance, but also to an episodic, unpredictable narrative without causal linkage. From God’s perspective, then, human history is a narrative with a meaningful plot, in which everything is “behovely”.

In spite of this conviction, A Revelation inserts two significant events into its own narrative and into that of world history which seem to come out of nowhere. These events are the visions of the two unknown actions which God will do at the end of time, and these two actions themselves.

The sight of the ‘deed which the blisseful trinite shall do in the last day ’ (32.19), a vision which possibly hints at universal salvation, is generated by a specific moment in the visionary sequence, the juxtaposing of the five locutions. Unlike in other visions, the narrator does not describe how this act of juxtaposing leads to the act of understanding or becomes the sight.

The vision of the second deed is even more tenuously related to the other events in terms of causality. Without any contextual remarks, the narrator opens the chapter by boldly stating:

Oure lorde God shewde that a deed shalle be done, and himselfe shalle do it […] and by me it shall be done […] and I shalle do right nought but sinne. (Rev. 36. 1-4)

[Our Lord God revealed that a deed will be done, and he himself will do it […] and it will be done with regard to myself […] and I shall do nothing but sin.] (85)

Neither the vision nor the event appears to result from earlier events in either the narrative or Julian’s life.

A Revelation at this point, then, seems to have become more of an “aventure” than A Vision, although the narrator claimed earlier that from God’s perspective no such “aventure” exists. Yet by thus seemingly exploding her own poetics, Julian strategically evokes that earlier discussion of providence, and in particular her exploration of how God, the ultimate “doer” behind all things, lovingly leads all events to the end to which he has predestined them in eternity (Rev. 11.30-45).

By giving a few events in her story such apparent lack of narrative coherence, Julian encourages the reader to see God instead of her as the ‘doer’ who leads all events in her narrative. According to A Revelation, then, God will reveal to the reader previously unseen causal linkage and narrative coherence during and after the reading process. Even events not yet showing that mother Christ is in control, ultimately will turn out to show exactly that, Julian promises. She thus makes Christ participate in and authorize her storytelling, just as she participates in his motherhood.

“The Trinity”. The Rothschild Canticles, Beinecke MS 404. f. 94r. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University Library, Yale. Image: Beinecke Digital Collections.

Heavenly Co-Authoring

This is not the only aspects of her poetics which may have surprised Julian’s contemporary readers. After wrapping each literary term in layer after layer of significance, both material and abstract, she finally collapses her literary terms into Christ, thus authorizing her poetics and her storytelling. (To use a more Julian term, she encloses it all in Christ).

Literary terms and formal features figuring the sacred do appear in other texts; the writer of the fifteenth-century life of Christ Speculum Devotorum points out to his readers that the prayer requests in the beginning, middle and end symbolize “that the Holy Trynytee ys the begynning, the myddyl, and the ende of alle good werkes” .

A Revelation, however, employs it literary terms in a manner similar to its use of the motherhood mother. As Andrew Sprung notes, when Julian compares Christ to a mother, God is not the vehicle but the tenor. Similarly, she writes “he is the grounde, he is the substance [meaning]” (Rev. 34.14), turns Christ into the “knotte” or gist by describing him as the means which ties together lived experience and essence (sensuality and substance) (Rev. 56. 10, 11), and in the last chapter exuberantly proclaims Christ (Love) to be the “mening” (meaning and intention) of the visions, and who and what the visions showed (Rev. 86). When she does so, she does not as much conflate all these literary concepts with Christ, but rather turns them —rather Neoplatonically— into only pale shadows of Christ, making Christ encompass them all.

According to Julian, the genuine form of the text and each of its thematic and formal features consists of Christ. Any formal feature the reader can discover only figures the ultimate form and concept, Christ. Simply put, Julian’s words are the Word. By extension, Christ is made the mother giving birth to the text, by means of Julian. Her statement about Christ’s birthing and parenthood emanating through earthly parents therefore applies to her understanding of storytelling as well: “it is he that doth it in the creatures by whom it is done” (Rev. 60. 44). [“[Y]et it is he who does it by the created beings by whom it is done.”’] (130). Thus, as a result of its poetics of the mother tongue, A Revelation can speak with maternal, divine authority, presenting Christ as Julian’s co-author.

Stubborn Word-Knots

To conclude, by means of its literary thought, A Revelation adds its unique contribution to contemporary debates about whether the vernacular could represent God’s word. Different Oxford theologians, authorities, and vernacular theologians disagreed vehemently about the (in)sufficiency of English to capture the intricacies and mysteries of the Biblical language; these debates led to Thomas Arundel, the archbishop of Canterbury, promulgating his Constitutions in 1409, which forbade the possession of unapproved vernacular religious texts and vernacular Bible translations. The resulting anxiety concerning vernacular religious texts may have prevented Julian from circulating A Revelation.

It should be stressed, however, that not only Lollards, but many other religious thinkers were in favour of vernacular Bible translations. Those who opposed translations, such as the Oxford theologians William Butler and Thomas Palmer warned against the carnality of the vernacular and of its speakers. By using Middle English literary terms, A Revelation engages in a dialogue with these discussions. Just like the prologue to the Wycliffite Bible, for instance, A Revelation not only recounts Christ’s words but also thinks aloud about how to best do so. By making its literary concepts more physical and maternal and using those to describe divine actions, Julian capitalizes upon the carnality of the vernacular. She reveals its supposed limitations to be its greatest resources.

According to Julian, then, mother Christ naturally speaks the mother tongue. Furthermore, by turning familiar literary terms into polyvalent, sometimes contradictory “word-knots” (to use Gillespie and Ross’ term), which she claims originate and figure Christ, she gives the lie to claims that Middle English cannot translate the different exegetical senses of the Bible and its obscurities. Finally, by making Christ the text behind hers, and the ultimate storyteller, she undermines the common opposition between doctrine (associated with the clergy) and narrative (associated with the laity): rather, Christ can only be known through stories.

Middle English was often called the “kinde language”: A Revelation, in sum, contributes a poetic Middle English, and a Middle English poetics that are “kinde” in its many senses: instinctive, natural, native, but also filled with the love between mother and child.

As a result, though she was enclosed and perhaps unable to share her text with her “evencristen”, Julian both speaks and transforms the language of the world outside her anchorhold.

Dr Godelinde Gertrude Perk