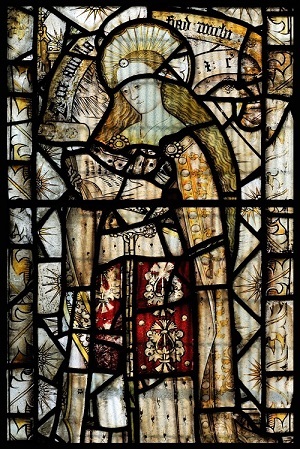

Project Image (Wikimedia Commons)

And so my two and half years’ association with the Leverhulme Trust Project, Women’s Literary Culture & the Medieval Canon, draws to a close. It’s a good opportunity for me to stop fiddling with spreadsheets awhile and ponder what I have learned as a result of contact, for the first time in my life, with scores of literary medievalists.

When I was offered the post of Project Facilitator in the Spring of 2015 I was delighted. I would combine my skills as an administrator with my love of literature and travel, all in nine hours a week. What could be better? There would be three events to organise; two workshops, in Chawton (2015) and Boston (2016), and a conference in Bergen (2017). The workshops would be smaller events, for a core of invited Network members, the conference larger, involving an open call for papers from academics around the world. My remit would be to organise venues, travel, hotels, restaurants, as well as to draft the programme and set up an associated website and blog. One of the main challenges was to book events in cities I had never visited. I am grateful for the support and advice of the Network academics on the ground, Amy Appleford in Boston and Laura Saetveit Miles in Bergen.

Chawton House Library, Chawton, Hampshire. (Photo by Lynette Kerridge)

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the location of a meeting will affect participants’ output, for good or ill! How could we fail with our first venue, Chawton House Library? It is the former home of Jane Austen’s brother and Jane was a frequent visitor. She sat, perhaps, on that very window seat in our heavily curtained, wood-panelled room. It was an inspiring ambience for a group of literary scholars. There was inspiration of a different nature at our second venue, the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies, Boston. A building of leather chairs, polished wood and pendulous chandeliers it spoke straight from the pages of a Henry James novel, in overwhelming contrast to the war-time experiences of its namesake, holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Elie Wiesel. Finally to the lofty proportions of the ultra-modern University of Bergen and The Egg, the aptly named conference theatre, suspended white and oval over the void, seemingly without support. This and the superb Norwegian open sandwiches provided fitting inspiration for the sixty or more scholars who presented papers.

Strangely I first began to engage with the subject matter of the project not at work but with friends. From some came waves of polite, thinly-veiled scepticism regarding the nature of the project. Accountants, doctors, engineers, there was little willingness to engage with the subject of medieval literature, let alone the role played by women in the canon. I found myself, with no particular axe to grind, discussing the project over dinners, trying in inarticulate fashion to explain the importance to our culture of literature and the thrill of historic literary discovery. This was first made real to me in a conversation with Nancy Bradley Warren in which she told me she would be rummaging in archives in ancient convents in France, rounding off her trip to Europe with a visit to the manuscripts in the British Library. Conversations with others revealed names of which I had only dimly been aware: Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe and the impossibly exotic sounding Mechtild of Hackeborn. These, I discovered, were women of flesh and blood, arguably semi-literate, relying often on male scribes, yet with unmistakable voices that have echoed down the centuries. Surely, I argued with my dinner companions, these faint voices deserved to be uncovered and amplified by experts in the field, much as an archaeologist might sift the sand painstakingly for clues?

Statue of Julian of Norwich, Norwich Cathedral (Wikimedia Commons, photo by David Holgate FSDC)

I must admit that the concept of the role of women as distinct to that of men in the medieval or indeed any other literary canon had never crossed my mind, except in the broadest of possible terms, when considering the remarkable lives and works of writers such as the Brontës or George Eliot. I had never considered how restricted the lives of women were in medieval times. New to me was the idea that the best (perhaps only) way for high status, intelligent women to maintain their independence and literary pursuits was to enter an abbey as a nun. Some women, for example those who preferred women and wished never to marry, might have done this willingly, for others, torn between marriage and children and the life of the mind, it must have been a tortuous choice. Yet others were no doubt forced into a life of religious seclusion, regardless of their wishes or intelligence. And then we have the Visionaries and those women such as Julian of Norwich who became anchoresses, shutting themselves away for life in anchor-holds attached to churches, dispensing wise words and prayers through an aperture in the wall. Remarkable women, doing remarkable things, some little of which has come down to us via the written word.

Of all that I have discovered and learned on my lay-person’s journey through medieval literature, two aspects have caught my imagination. Firstly, the concept of the anchoress as mentioned above, secondly the research by Michelle M Sauer and others on Christ’s wound and the use of this image in medieval worship and art. My husband and I are frequent visitors to village churches on our travels round the UK and I was recently staggered to find an example at the Church of St Michael the Archangel, Laxton, Nottinghamshire, the oldest parts of which date back to 1190. Here, on the North Aisle Screen, I was amazed to discover the five wounds of Christ, roughly carved into the wood in 1532. These, I read, were carved as an act of rebellion against Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. One can imagine an angry, frightened wood-smith gouging the wood in haste, creating these secret symbols of rebellion to encourage others. The insurgence was ruthlessly suppressed but the wounds, literally and figuratively, remain to this day. To read Michelle M Sauer’s fascinating blog please click here.

Christ’s Wounds, Church of St Michael the Archangel, Laxton, Notts. (Photo by John Kerridge)

North Aisle Screen, Church of St Michael the Archangel, Laxton, Notts. (Photo by John Kerridge)

There is a poster on the wall near my office which says this: ‘A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies. The man who never reads, lives only one.’ Aside from the lazy sexism implicit in these words, I wholeheartedly agree with the sentiment. As a child I was Alice, Mary, Roberta, Darryl, Lucy, Gemma, George, Marianne. As an adult I have inhabited countless souls. Now I add more: Birgitta, Margery, Julian, Mechtild and my life is immeasurably enriched.

Lynette Kerridge