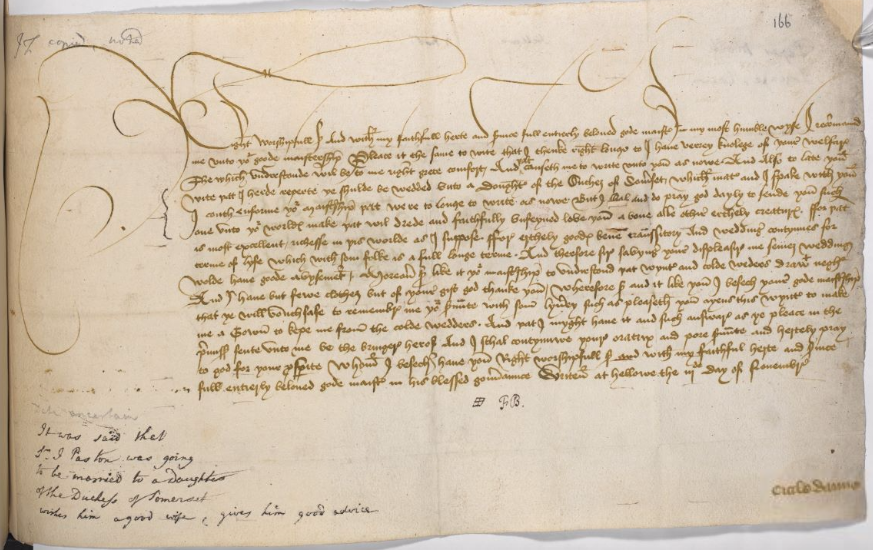

The letter of Cecily Daune in British Library Add MS 34889 f.166. Screen shot of the digitised image. Copyright The British Library.

I am currently working on a project to transform into modern English and poetic form letters by fifteenth-century women connected to the Paston family of Norfolk. The project involves translation from one vernacular to another – medieval to contemporary – and choices which change prose into poetry. The purpose is to help bring alive what seems undeservedly lost to a non-specialist readership.

The original letters (read in the Norman Davis OUP editions of 1971 and 1976) resonate with particular power when read aloud – perhaps because so many were dictated, as were many men’s letters at the time. The letters also press home their points with a decidedly literate awareness of how to handle language. To respect the women’s voices and their craft, each poem is written as a dramatic monologue with an attention to vocabulary, line and stanza length and rhyme which aims to reflect the women’s thinking and expression in their prose.

Here is an example of work in progress: the letter from Cecily Daune, a mistress of John Paston II, first son of John Paston I and Margaret Mautby Paston. This is letter 753 in Davis’s edition. Davis dates the letter to 3 November 1463-1468. John II as a lawyer like his father and grandfather, ‘Judge William’. He looked after the Paston affairs in London and had just been knighted. This letter was more recently translated by Diane Watt in The Paston Women: Selected Letters (Boydell & Brewer, 2004), 125-126.

My poem works, as does all poetry in some way, through the art of compression.

Right worshipful sir and most beloved good master,

I think about you always, and draw comfort

that you know this and will tell me how you are.

The solace is most needful

having heard what I have heard – that you might

wed a daughter of a Duchess – Somerset – oh,

I could say of her so many words.

I pray to God you will be heedful that when

you marry, it will be to a woman who loves

you above her life – for that is the greatest

gift from God, when He blesses man and wife.

All the rest is dust.

Winter comes, the bitter winds begin to blow,

and I must beg you to understand that I have

few clothes in press – these are much valued

as your gift – yet I need something warmer now

against the wind and snow. Will you write?

I shall continue to pray for your wellbeing and

prosperity – and that, right worshipful sir and most

beloved good master, you will remember me.

The poem is written in free verse in three stanzas of diminishing length. Davis gives three diminishing length paragraphs but the stanza forms reflect more starkly not only changes in focus but also a diminution of narrative energy and a darkening mood.

The opening three lines of the first stanza compress the conventions and flatteries of the first two sentences whilst also reflecting Cecily’s understandable claim for attention. There follows a deliberate double juxtaposition of ‘I’ and ‘you’ following Cecily’s reference to the gossip she’s heard about a prospective marriage (or misheard, as the gossip was actually about John’s uncle, William Paston II). The half-rhyme of ‘heard’ and ‘words’ in lines five and seven hint at the uncertainty of rumour, whilst the double ‘I’ and ‘you’ at the start of lines seven to ten re-create the ‘I’/’you’ tension in the third sentence of the letter. It is as though the language insists on their partnership.

The last part of the first stanza reflects Cecily’s passionately (and yearningly) positive statement about the gift of marriage with a full rhyme (‘life’ and ‘wife’) and an easy flow of unpunctuated lines (eight to eleven). This creates a contrast with the deliberately broken lines about the rumour (lines five and six). The brief final line of the first stanza with its five heavy monosyllables and reference to deathly ‘dust’ dramatises the original prose to emphasis a difference from the preceding lines on marriage and to underline Cecily’s reflection on what she does not at present have.

Paragraph two in the original, as given by Davis, moves to Cecily’s request for more clothes. (Professor Watt has drawn attention to her use of the word ‘livery’. To what trade, if any, did Cecily belong? She was clearly dependent on John II.) I have kept Cecily’s simple reference to ‘winter’ but made more of ‘colde wedders’ with ‘bitter winds begin to blow’, picking up nevertheless on her own use of alliteration. As in stanza one, the last line is short and clear but this time hedged by uncertainty – ‘Will you write?’ The stanza break here fills with the pain of unknowing.

The final short stanza stays close to the original prose in vocabulary and expression but ends with an imagined phrase, ‘remember me’. It’s a simple phrase that resonates with all of us and it has a particular impact when voiced by a forgotten woman to a powerful man. The poem responds to her request. Remember you? Yes, Cecily, we do.

Dr J.J. McFarlane September 2017