by Sue Niebrzydowski, University of Bangor

In 2018 celebrations are being held throughout the United Kingdom to mark the centenary of women who owned property and were over thirty getting the vote. Feminist medievalists will be delighted, and very possibly surprised, to learn that the first female dramatist, Hrotsvit, canoness of Gandersheim Abbey (c.935 – c.975) is linked to the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Another talented dramatist, Christopher ‘Chris’ St John (aka Christabel Gertrude Marshall (1871-1960)); actress, playwright, translator, and suffragette, recognised in the tenth-century canoness a kindred spirit for whom drama was a means to draw attention to women’s lives.

St John was born in Exeter, the youngest of nine children of the novelist Emma Marshall (1828–1899) and Hugh Graham Marshall (c.1825–1899). Educated from 1890 at Somerville College, Oxford, St John was one of the first women to go to this institution ‘founded to include the excluded […] created for women when universities refused them entry.’ St John studied Modern History (achieving a BA third class but could not matriculate), after which she became, briefly, secretary to the anti-suffragist, Lady Randolf Churchill, and occasionally to her son, Winston. Her private life, like her literary career, was pioneering. St John had a life-long relationship with Edith ‘Edy’ Craig, the daughter of the actress Ellen Terry, with whom she lived from 1899 until Craig’s death in 1947. In 1916 the couple were joined by the artist, Clare ‘Tony’ Atwood, living in a ménage à trois until Craig died.

In 1909 St John joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), having previously worked for the Women Writers’ Suffrage League and its sister organisation, The Actresses’ Franchise League (AFL; 1908-1914), created to convince members of the theatrical profession of the necessity of extending the franchise to women. The purpose of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League was, as stated by its president, Elizabeth Robins, ‘to obtain the Parliamentary Franchise for women on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men, its methods are the methods proper to writers – the use of the pen.’ The AFL was strictly neutral with regard to suffrage tactics, and neither endorsed nor condemned militant protest campaigns. 1909 proved to be St John’s year of militancy for it was in this year that she was arrested, either for obstructing the police outside the House of Commons or for setting fire to a pillar (letter) box. Although the precise nature of her civil disobedience is uncertain, both options suggest a woman unafraid to act on her convictions.

St John’s plays focus on women’s rights and her oeuvre includes How the Vote was Won, a one-act play co-written with fellow playwright and actress, Cicely Hamilton (b. Cicely Mary Hamill, 1872). Cicely Hamilton was also a founder member of the AFL and the Women Writers Suffrage League. Hamilton also wrote another propaganda play, A Pageant of Great Women (1910), and joined with the Surrey composer and Suffragette, Ethel Smyth, to write March of the Women (1910).

In 1911 Chris and Edy co-founded The Pioneer Players (1911-20, 1925), a relatively small theatre society, based in London. St John’s play, The First Actress, dramatizing male attitudes to the first female actors on the London stage in Killigrew’s Company in 1661 was performed in May 1911 by the recently founded Pioneer Players in the ‘Women’s Suffrage Matinèe’ at the Kingsway Theatre, London. The play was well received although one male reviewer was clearly somewhat confused, praising Mr St John for putting ‘some charming little speeches into the mouths of irresistible ladies’ (Review in The Standard, London, May 1911). Among these ‘irresistible ladies’ was none other than Ellen Terry who played the part of Nell Gwynne.

On 11 and 12 January, 1914, Craig directed St. John‘s translation of Hrotsvit’s Latin play, Paphnutius. In this play a prostitute, Thais (played by Miriam Lewes), is converted by a confessor figure, the priest Paphnutius (Harcourt Williams) and guided by an Abbess (Ellen Terry). The plot punishes Thais for her sin and she suffers misery and confinement in ‘a narrow cell.’ On her release Thais dies but the play has an uplifting ending since Thais dies redeemed and assured of her place in Heaven.

Encouraged by her Abbess Gerberga who was the niece of Otto I, Hrotsvit wrote six Latin plays – Gallicanus, Dulcitius, Callimachus, Abraham, Paphnutius, and Sapientia – in rhymed prose, because, as she tells us:

I, the strong voice of Gandersheim, have not hesitated to imitate in my writings a poet whose works are so widely read, my object being to glorify, within the limits of my poor talent, the laudable chastity of Christian virgins in that self-same form of composition which has been used to describe the shameless acts of licentious women. (Katharina M. Wilson, ed., Medieval Women Writers (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), 30-46).

Hrotsvit repurposes the plays of the classical playwright, Terence, to champion female chastity. At the close of each of Hrotsvit’s plays, good triumphs over evil. Hrotsvit’s heroines find support from chaste men (as in Paphnutius) but predominantly from like-minded women who guard their chastity for their faith, and offer their younger sisters support and guidance.

It is perhaps of little surprise that Hrotsvit’s propagandist drama and the strong women whom she portrayed appealed to Christopher St John, and were deemed appropriate subject matter for the Pioneer Players. The determination of the early medieval playwright and her female protagonists echoed that of St John and her contemporaries as they sought the vote.

The Pioneer Players’ commitment to this play is evidenced by the lengths to which they went to present it to the public. Edy recorded in her memoirs that Paphnutius could not be performed at the original intended location – the National Sporting Club (a boxing club in Covent Garden) – since a ticket had been sold, erroneously, and to a detective at that, thus endangering the licence of this private members’ club (Ann Rachlin, Edy was a Lady (Matador: Leicester, 2011), p. 53). Edy managed with some difficulty to secure the agreement of H. B. Irving and D’Oyly Carte to transfer the play to the Savoy Theatre which she realised had ‘curtains suitable to Paphnutius […] and an apron stage’, which they duly did, taking ‘hand-barrows from Covent Garden Market and wheeled the things round to the Savoy’ (Rachlin, p. 53). She reports that they played to a bumper house for both the Sunday show and the Monday matinee.

Egan Mew, theatre critic for The Academy, was enthusiastic about the play, reserving special praise for its scenery,

Miss Craig’s setting of the scenes is beyond praise. Although we are at the Savoy Theatre of many memories we are mentally transferred in a moment to the dusty desert […] or to the rich rooms of Thais within the city, to the monastery or, indeed, to any scene which the play requires. (Egan Mew, ‘The Pioneer Players in “Paphnutius” at the Savoy Theatre’, The Academy, January 17, 1914, 88-89 (p. 89))

Clearly, the exertions with the hand-barrows had not been in vain.

Having commenced with Paphnutius, St John went on to produce the first complete translation of Hrotsvit’s six plays into English between 1912 and 1914. St John explains why she undertook this enterprise:

The lively interest provoked by the stage performance of one of the translations (that of the play Paphnutius by the Pioneer Players in January 1914) led me to think that the publication of the whole theatre of Roswitha in English would be welcomed by all students of the drama. (The Plays of Roswitha, Preface, p. xiv)

St John recognised the significance of Hrotsvit, and the contribution that familiarity with and a better understanding of her plays might make to the study of drama. St John’s project to see Hrotsvit’s plays made available in English did not go smoothly, however, as St John reveals, ‘Unfortunately, the war delayed publication, and the manuscript was entirely destroyed by a fire at the publisher’s premises in Dublin during the Irish insurrection of Easter 1916’ (The Plays of Roswitha, Preface, p. xiv).

Undeterred, St John began again, examining all of the extant Latin editions of Hrotsvit’s plays including the Opera Hrotsvitae of Conrad Celtes (the first Latin edition of her works created in 1501), and that in J. P. Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus (Volume 137), and also the chapter on Hrotsvitha in Alice Kemp-Welch’s 1913 publication, Of Six Mediaeval Women to which is added a note on mediaeval gardens.

St John turned to another strong woman, Dame Laurentia Margaret McLaclan OSB (1866-1953), Abbess of Stanbrook, near Worcester, and first woman vice-president of the Henry Bradshaw Society (founded in 1890 to edit rare liturgical books), to help her with the translation.

Preparing a second manuscript of her translations of Hrotsvit’s plays was a labour of love, especially as the moment of ‘Hrotsvitmania’ appears to have passed, as acknowledged ruefully by St John,

to begin it all over again was a heart-breaking task. The consciousness that the interest in Roswitha provoked by the performance of Paphnutius had waned did not alleviate the heaviness of spirit in which the work of replacing the burned manuscript was undertaken. (The Plays of Roswitha, Preface, p. xv)

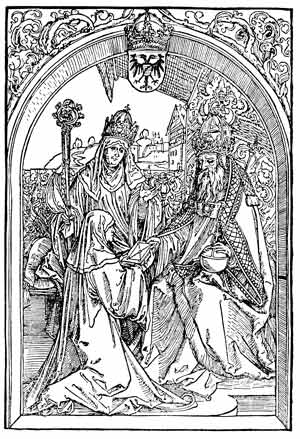

Testimony to her determination, St John’s edition of Hrotsvit’s plays was finally published by Chatto and Windus in 1923. The volume includes a reproduction of the 1501 woodcut by Albrecht Dürer created for Celtes’ edition of Hrotsvit’s works, showing Hrotsvit presenting the aged emperor Otto the Great with her Gesta Oddonis, under the eyes of Abbess Gerberga. It is tempting to read in Dürer’s woodcut of Hrotsvit and Gerberga a prefiguration of the collaborative relationship of St John and Laurentia Margaret McLaclan, Abbess of Stanbrook, a millennium later.

Woodcut from the Roswitha editio princeps 1501, Albrecht Dürer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

St John translated Hrotsvit’s plays in the spirit of a commitment to historical women’s literary achievement. In 2018 we should commemorate this remarkable relationship of a suffragette and a nun, sisters in drama for whom this medium offered opportunity to celebrate women’s lives and promote change.

Further Reading

Primary Reading

The Plays of Roswitha, ed. and translated by Christopher Marie St. John, with an introduction by Cardinal Gasquet and a critical preface by the translator (London: Chatto & Windus, 1923).

Secondary Reading

Andes, Anna, ‘The Evolution of Cicely Hamilton’s Edwardian Marriage Discourse: Embracing Conversion Dramaturgy’, English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, Volume 58, Number 4 (2015), 503-522.

Cockin, Katharine, ‘Cicely Hamilton’s warriors: dramatic reinventions of militancy in the British women’s suffrage movement’, Women’s History Review Volume 14 Issue 3-4 (2005), 527-542.

Cockin, Katharine, ‘Edith Craig and the Pioneer Players: London’s International Art Theatre in a ‘Khaki-clad and Khaki-minded World’ in A. Maunder, ed. British Theatre and the Great War, 1914–1919 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Cockin,Katharine, Women and Theatre in the Age of Suffrage: the Pioneer Players, 1911-1925 (New York: Palgrave, 2001)

Crawford, Elizabeth, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866-1928 (UCL Press, 1999).

Engle, Sherry, and Susan Croft, eds., Thousands of Noras: Short Plays by Women, 1875-1920 (IUniverse: Bloomington, 2015).

Hamer, Emily, Britannia’s Glory: A history of Twentieth Century Lesbians, p. 31.

Holroyd, Michael, A Strange Eventful History (London: Chatto and Windus, 2008).

Kuehne, Oswald R., ‘Recent Literature Concerning Hrotsvitha,’ The Classical Weekly, Volume 20, No. 19 (March 21, 1927), 149-150.

Newman, Florence, ‘Violence and Virginity in Hrotsvit’s Dramas’, in Hrotsvit of Gandersheim: Contexts, Identities, Affinities, and Performances, ed., Phyllis R. Brown, Linda A. McMillin and Katharine M. Wilson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 59-76.

Rachlin, Ann, Edy was a Lady (Matador: Leicester, 2011)

Robins, Elizabeth, Way Stations (Hodder and Stoughton, 1913), p. 106.

Wilson,Katharina M., ‘The Saxon Canoness: Hrotsvit of Gandersheim’ in Katharina M. Wilson, ed., Medieval Women Writers (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), 30-46.