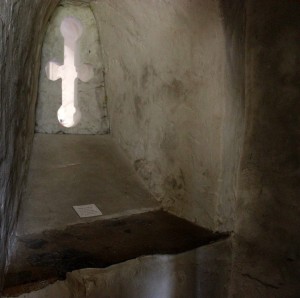

Anchorite’s Cell, St Nicholas, Compton. (c) Heike Bauer. Reproduced with permission.

by Diane Watt, University of Surrey

Anchorites were individuals, sometime laypeople rather than members of formal monastic orders, who lived a life of religious contemplation focused on prayer and devotion to the Eucharist. Theirs was a life of extreme enclosure, as they were quite literally walled up in cells permanently attached to churches. In other words, they chose a life of solitude paradoxically located in the heart of the community.

In the later Middle Ages, the anchoritic movement grew considerably in popularity, especially amongst women. The cells were spaces of strict physical isolation, the boundaries of which were, at least theoretically, carefully policed. An early example of an English woman who chose the solitary life is Eve of Wilton (c.1058-c.1125). Eve joined Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire as a young girl, but left, apparently abruptly, in c.1080 to become a recluse in France, initially in Angers. She subsequently moved to St. Eutrope.

Shortly after her departure from Wilton, Goscelin of St Bertin, a Flemish Benedictine monk based in England, wrote the Liber confortatorius [Book of Consolation]. This long epistolary text is addressed to his former pupil Eve and in it he laments her absence and offers her guidance in her new vocation. For example, Goscelin advises Eve to ensure that she avoids the evils of the outside world:

Let the windows of your cell, your tongue and your ears be locked to false tales and idle talk, which is better named malicious talk.

(Book of Encouragement, trans. Otter, 94-5).

The apertures to Eve’s cell are equated with the openings of her body, vulnerable to corruption, and therefore they should be carefully sealed up against the evils of rumour and gossip.

For Goscelin, however, the cell is also a space of scholarship. Drawing again on the architectural image of the window as the connection between Eve and the outside world, but to very different and more positive effect, he encourages her to remain open to learning:

I would like the window of your cell to be wide enough to admit a library of this size, or to be wide enough that you could read the books through the window if they are propped up for you there from outside.

(Book of Encouragement, trans. Otter, 95-6).

Indeed Goscelin has confidence in Eve’s ability to manage her own instruction and he provides her with a programme of reading that includes Augustine’s Confessions and City of God, Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History and its continuation, Orosius’s De Ormesta Mundi [History of the World or History Against the Pagans] and Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy (Book of Encouragement, trans. Otter, 96). Intellectually, at least, Goscelin does not consider Eve to require close monitoring, but rather believes she should be supported in independent study.

In fact, Goscelin—who found himself forced by circumstance to become something of an itinerant hagiographer, moving from one religious house to another following commissions to chronicle their spiritual histories—claims that he actually envies Eve her cell:

I cannot tell you how often I have sighed for a little refuge similar to yours (though one that would have a door for solemn exits, that I may not lack a larger temple) where I might escape the crowds that tear at my heart; where I might pray, read a little, write a little, compose a little; where I might have my own little table, so that I could impose a law on my stomach and on this pasture feast on books rather than food; where I might revive the dying, tiny spark of my little intellect, so that, unable to be fruitful in good deeds, I might yet be a little fruitful by writing in the house of the Lord.

(Book of Encouragement, trans. Otter, 32-3).

Goscelin envisages the anchoritic cell as having the potential to be a space of contemplation, reading, writing and ascetic self-restraint; a library and study combined. He longs to inhabit such a space himself but is constrained by his priestly role and the need to access the church in order to celebrate the mass. Eve’s cell would have been attached to a church, and may have had a squint, allowing her a view of the altar and to participate in the mass, but she would not have been able to enter the building itself.

Eve was able to write as well as to read: Goscelin alludes to the fact that they formerly exchanged letters when she resided in Wilton, and he begins his Liber by inviting her to resume this activity. However, he does not imagine Eve’s cell as a place in which she will pursue her own writing. The composition of written texts is not an activity generally ascribed to anchoritic women in the High and Later Middle Ages, and it is not known whether Eve ever read or even received the Liber, far less composed her own response to it.

Despite that fact that no letters or other writings by Eve have survived, Goscelin’s Liber provide insights into the literary culture of intellectually, spiritually and socially élite English women immediately after the Conquest. It contributes to our understanding of their learning, their opportunities for scholarship, and of their access to books.

A figure like Eve of Wilton is important not only because she lived, wrote and studied at the key transitional point in English history, but because, like many women and men before and after her, she benefited from an education influenced by and fostered in continental Europe.

This post was originally published on the Spiritual Landscapes blog on 2 June 2017. It is republished here with permission.