Explore Your Archive is an annual campaign, organised by the Archives and Records Association, to promote, publicise and celebrate archives and special collections across the UK. This year the week runs from the 20th to 28th November and there is a focused social media campaign around various themes, one of which is handwriting.

© University of Surrey

Whilst thinking about this theme and how we could share some of our handwritten items it occurred to me that unless it is a requirement of our occupation or studies, we probably don’t regularly read other people’s handwriting. This can make handwritten archival documents seem rather alien and challenging to read. It can take a great deal of skill and experience to read old documents but don’t let that put you off, there are exciting and often unexpected things to be discovered!

When reading and interpreting handwriting it is important to remember that spelling, language and usage of words has changed over time. Before English was standardised words were spelt phonetically and these spellings would have varied by region and local pronunciation. So, along with the difficulty of deciphering unfamiliar handwriting, sometimes there is the added complication of weird and wonderful spellings. The original purpose of the document may also influence the style of writing and language. Was the document originally only intended for private use or was the individual using their ‘best’ handwriting as they knew it was going to be read more widely?

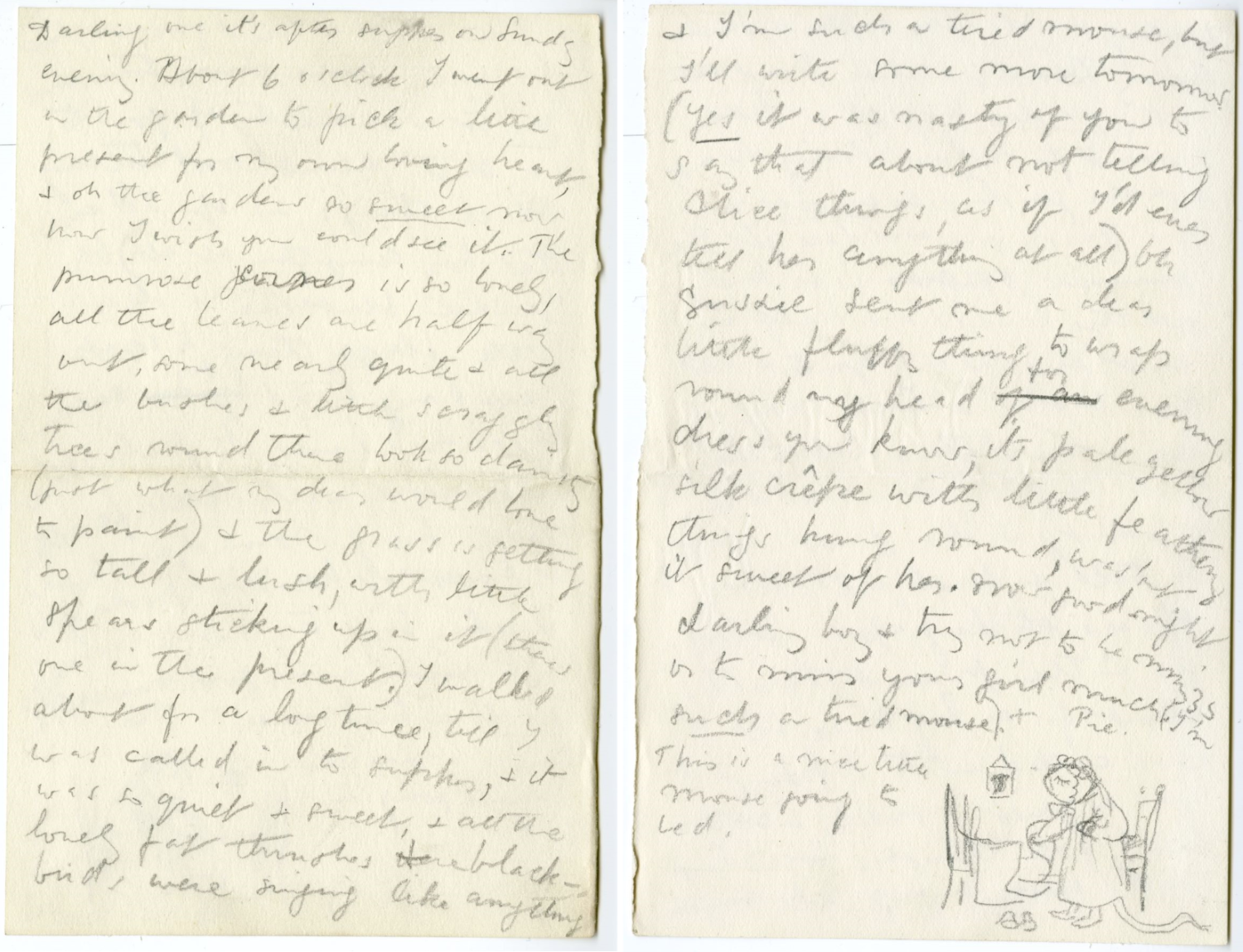

Illustrator E. H. Shepard and his first wife Florence regularly wrote to each other whenever they were apart. They occasionally included sketches in the letters; a personal touch that is perhaps lost in the age of instant messaging and emails. We are very lucky as we hold letters from Ernest to Florence and also her letters to him. They would have been very familiar with each other’s handwriting but to us the writing in the letters can be tricky to decipher.

In this letter from Florence to Ernest, sent a few months before they were married, some of the words are difficult to read but she describes how sweet the garden is and how she wishes that Ernest could see it. At the top of the second page Florence writes ‘…I’m such a tired mouse but I will write some more tomorrow’, at the bottom of the page she again writes ‘…(I’m such a tired mouse)’ and she has drawn a lovely little sketch of a mouse going to bed.

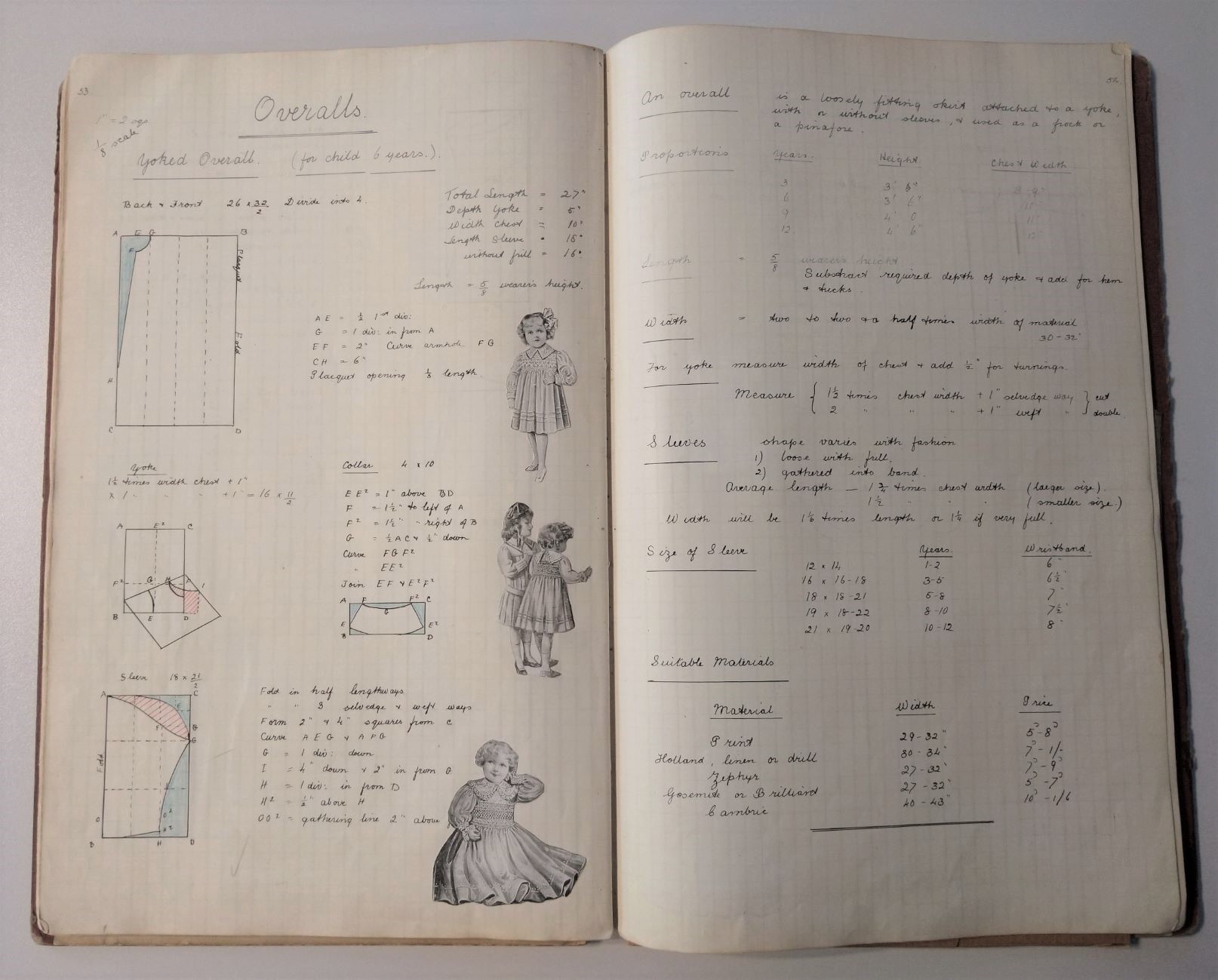

In contrast to Florence’s letter to a loved one, the handwriting in this Battersea Polytechnic student’s notebook is neat, and precise in style. This student may have always written very neatly but perhaps there was an incentive to write clearly to ensure the notes could easily be read at a later date.

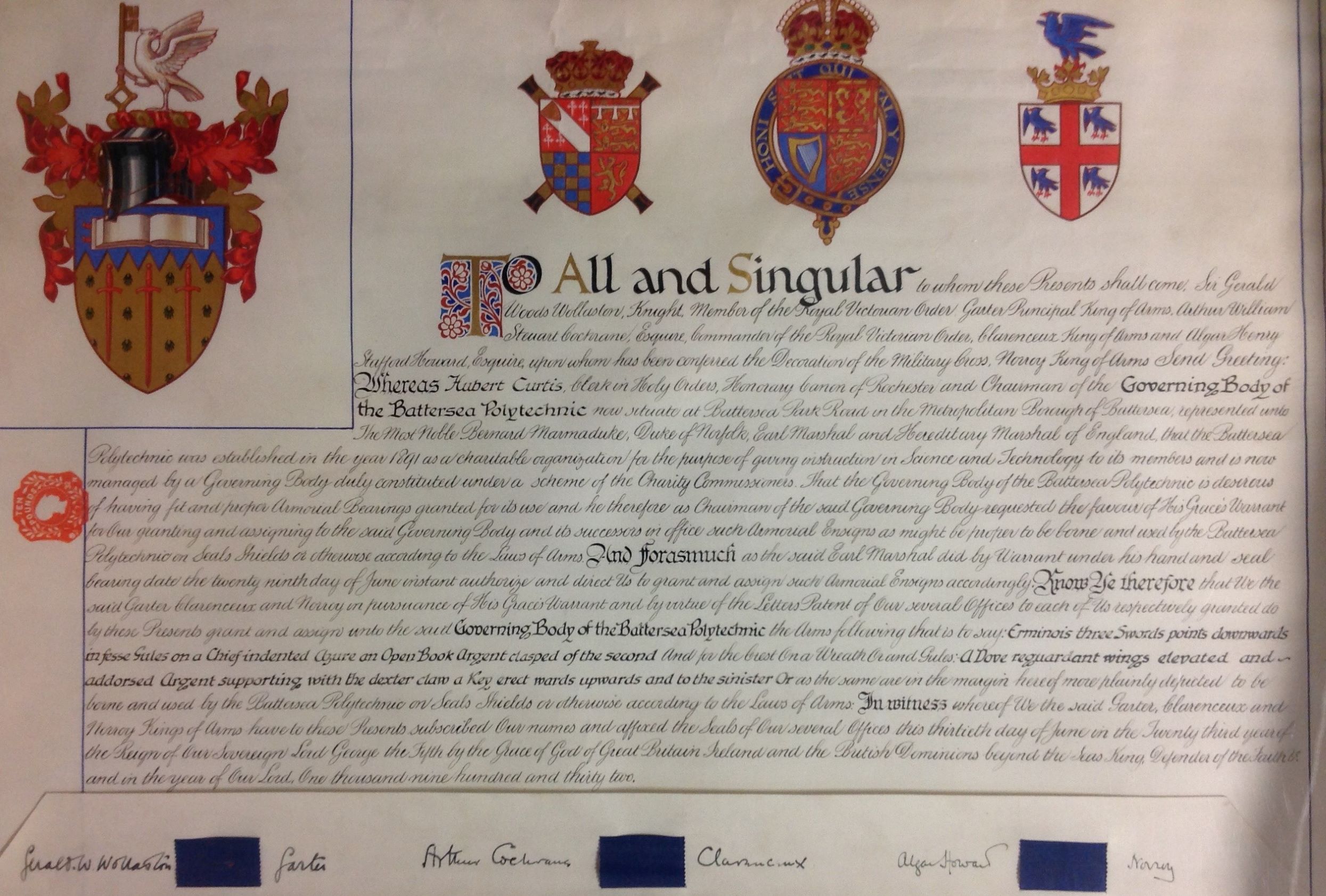

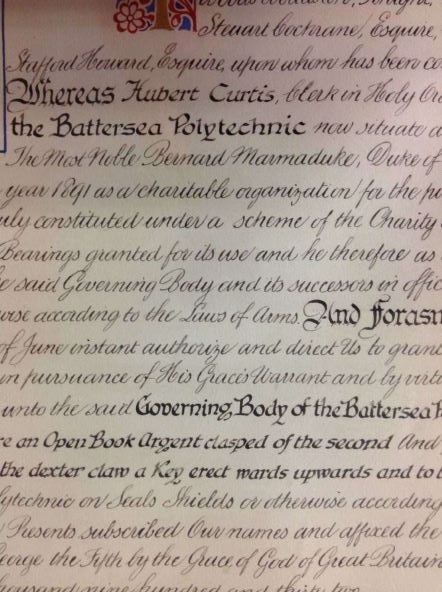

A very different example of handwriting, also from the Battersea days, can be found in the Battersea Polytechnic Grant of Arms. This beautiful manuscript would have been created by specialist scriveners and heraldic artists of the College of Arms. This traditional style of English manuscript writing and illumination can be traced back to the monastic scriptoria of the dark ages (source: www.college-of-arms.gov.uk) .

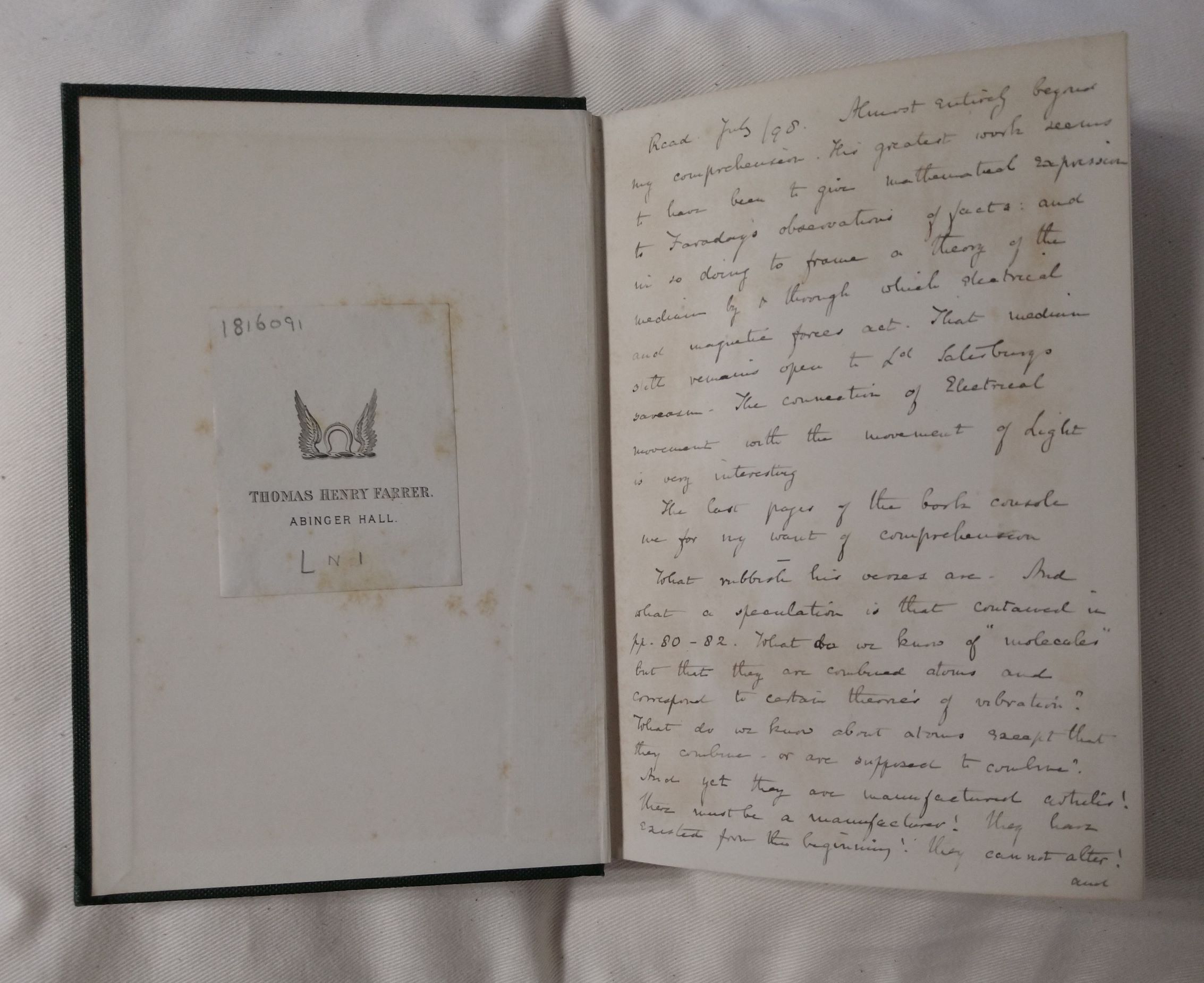

Being able to read and interpret handwriting isn’t just for documents. Our Thomas Farrer collection of rare books is made up of over 2,000 volumes and many of the books contain handwritten notes and comments made by Farrer.

In the front of the book ‘James Clerk Maxwell And Modern Physics’ Farrer has written a lengthy review of the book which just over halfway down the page includes the phrase ‘What rubbish his verses are’.

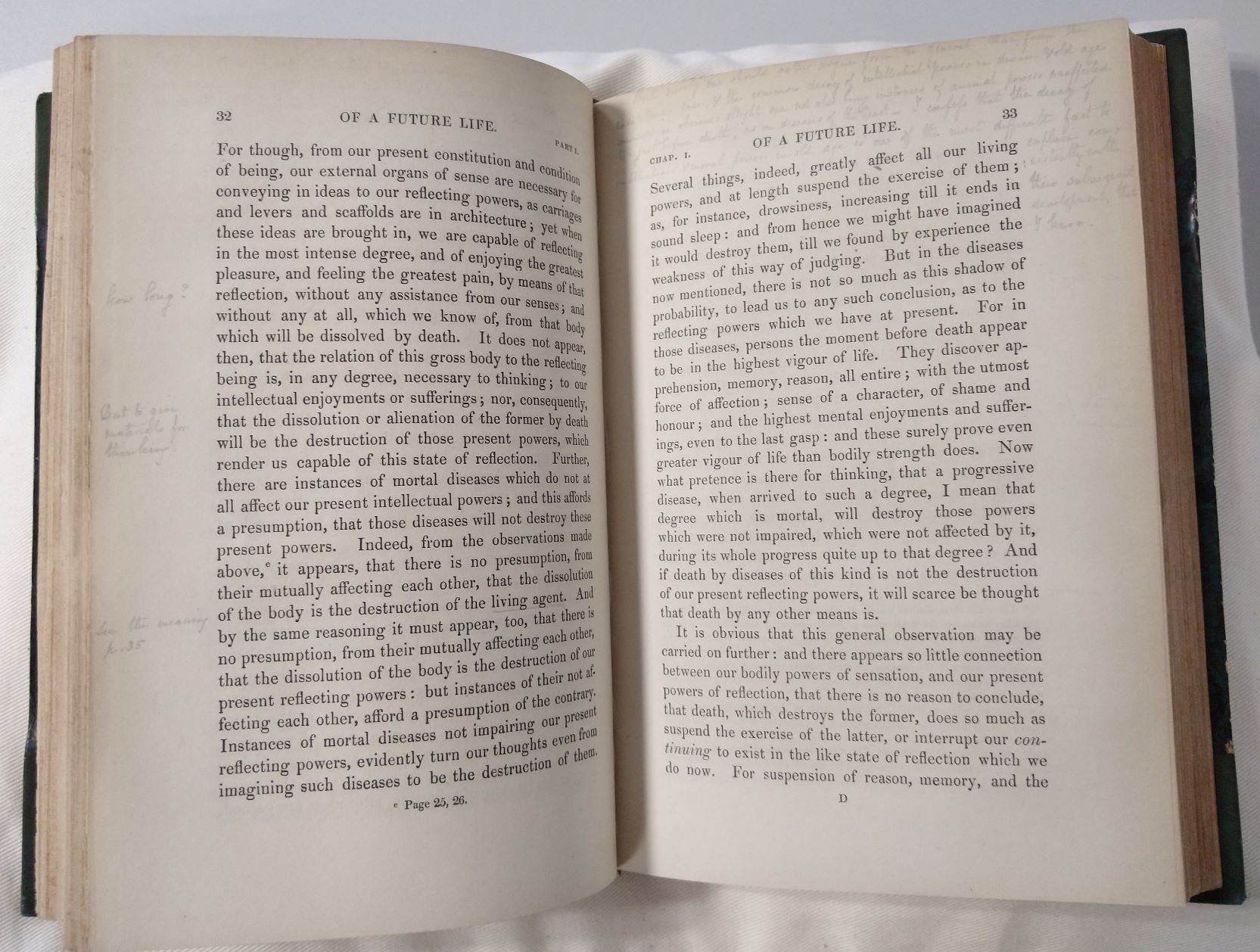

Thomas Farrer also made notes in the margins of many of his books

If you would like to learn more about the study of old handwriting there are lots of palaeography resources available, for example, The National Archives have an online tutorial to help you develop and practice your skills: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/

If you are interested in viewing items from our collections, please email archives@surrey.ac.uk and we can arrange an appointment for you to visit our Research Room.