February marks LGBT+ (Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans +) History Month, an annual celebration of the lives and achievements of the LGBT+ community.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the first Gay Pride march in the UK which took place in London on 1 July 1972 and this was certainly a topic of discussion amongst those who attended the University of Surrey LGBT+ History Month launch event and march on the 2 February.

50 years on from that first Pride March there have been huge leaps forward in LGBT+ rights and visibility. LGBT+ History Month gives us the opportunity to celebrate these successes but also offers the chance to reflect on the many difficult aspects of our shared history.

In 1967 the Sexual Offences Act decriminalised homosexual acts between men over 21 years old and in private. The Act only applied to England and Wales, with Scotland passing legislation in 1980 and Northern Ireland in 1982.

The years of criminalisation, discrimination, prejudice and abuse has resulted in individuals having to hide their true selves and this invisibility has often meant that their stories and experiences have not been reflected in archive and historic collections. This is just what LGBT+ History Month endeavours to address.

Even when an individual’s personal papers have been saved and given to an archive the records retained may not reflect every facet of their life. Items may have been lost or destroyed or intentionally removed before the records were deposited and unless the individual had publicly discussed their sexual and/or gender identities this aspect of their life may remain hidden. However, with research and exploration stories can be pieced together, for example, letters and diaries might reveal relationships that were not discussed openly at the time.

Surrey History Centre, which is based nearby in Woking, has a vast array of resources to help discover the region’s LGBT+ history and they actively encourage records to be placed with them. Until the end of February they have a display in their foyer which features faces from Surrey’s rich and varied LGBT+ past across the centuries.

The website ‘exploring surrey’s past’ created by Surrey Heritage and its partners, features some fascinating insights to in LGBTQ+ history and has some amazing resources to help get you started with your research: https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/subjects/diversity/lgbt-history/

On the website they have also shared the stories of some LGBTQ+ icons who have links to the county of Surrey. Reading these biographies made me wonder if we might have items in our archive collections that are related to their lives or have connections to the University.

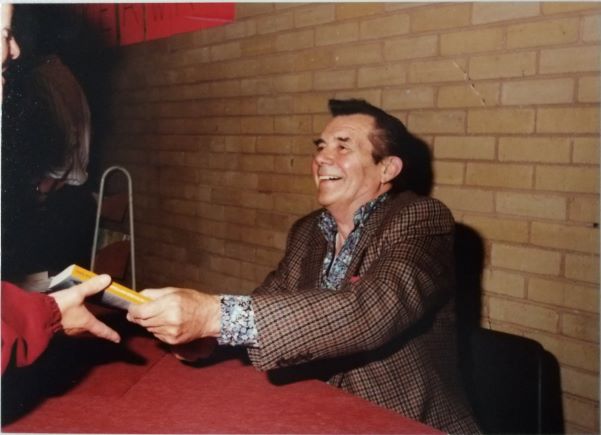

The actor Dirk Bogarde (1921-1999) was an officer in the Queen’s Royal (West Surrey) Regiment and for a time lived in Hascombe near Godalming. He lived with his agent Anthony Forwood for 40 years and during his career Bogarde publicly denied that the relationship was anything other than a friendship. As homosexual acts were illegal for much of Bogarde’s career, coupled with the need to maintain a Hollywood persona the reasons behind the denial are understandable. Later in his life he was able to be less guarded about being gay. In one of his most controversial roles, the 1961 film ‘Victim’ he played a married man blackmailed over a homosexual affair. A feature on the British Film Institute (BFI) website notes that Bogarde burned much of his paperwork in the 1980s but fortunately he had already donated many of his files to the BFI in 1970. Selected images of Bogarde’s annotated manuscripts can be viewed on the BFI website: https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/between-lines-hidden-drama-dirk-bogardes-scripts

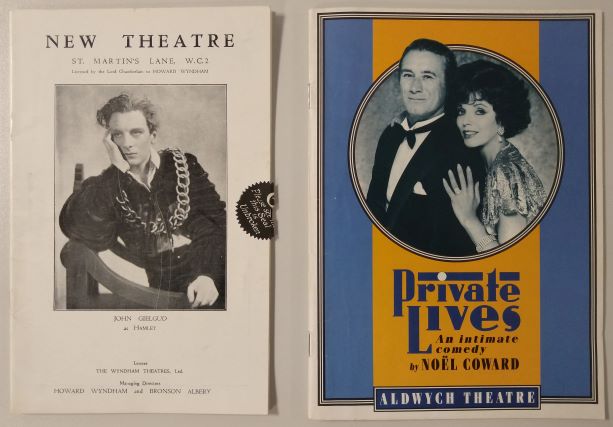

The renowned actor and director Sir John Gielgud (1904-2000) attended Hillside Preparatory School in Godalming. During his career Gielgud did not hide his homosexuality, but he never discussed it openly. In 1953 he was charged with ‘persistently importuning men for immoral purposes’ a crime that could have ruined his career. The play ‘Plague Over England’, written by Nicholas de Jongh, which premiered in 2008, dramatised this incident and the play suggested that this high-profile case helped to accelerate the decriminalisation of homosexuality.

Sir Noel Coward (1899-1973) was conscripted in March 1918 into the East Surrey Regiment, but he was found to be medically unfit for military service and discharged later the same year. He never publicly confirmed that he was homosexual, but much is now known about his relationships. The University of Birmingham holds the Noel Coward Collection which runs to 174 boxes and 59 files and contains a wide variety of material relating to his life and career.

The items I have selected from our collections, pictured above, have a serendipitous link as the New Theatre where Gielgud performed Hamlet was renamed the Noel Coward Theatre in May 2006.

As well as looking after the archive collections, the Archives and Special Collections team also look after the University’s Art Collection and this includes the sculptures that enhance our campus. One of the most prominent sculptures is that of Alan Turing (1912-1954) which can be found in the centre of the Piazza. There is a local link as Turing’s parents lived in Ennismore Avenue, Guildford and following his death in 1954 he was cremated at Woking Crematorium and his ashes scattered in the crematorium gardens.

Much has been written about the life, work, and death of Alan Turing. He is famous for his work at Bletchley Park during the Second World War and his exceptional contribution to the breaking of Enigma codes used by the Germans. He is also considered to be the father of modern computer science.

In 1952 Turing was prosecuted for homosexual acts under section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. As an alternative to imprisonment Turing was instead subjected to a chemical hormone treatment which had an enormous negative impact on his life. A petition was started in August 2009 asking the Government for an apology for its prosecution of Turing. In September 2009 Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued an apology for the inhumane treatment of Turing.

On the 24 December 2013 a Royal pardon came into effect, the Government press release issued on that day stated:

Royal pardon for WW2 code-breaker Dr Alan Turing

Renowned scientist and World War II code-breaker Dr Alan Turing has been given a posthumous pardon under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy by the Queen today following a request from Justice Secretary Chris Grayling.

A copy of the pardon was included in the press release and it is available for download: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/royal-pardon-for-ww2-code-breaker-dr-alan-turing

The Policing and Crime Act 2017 automatically pardoned men who were convicted of certain consensual gay sexual offences which would not be offences today. This law has been described as the ‘Alan Turing Law’.