A survivor in our archives:

Marcel Marceau (1923-2007)

For Holocaust Memorial Day 2024, Archives and Special Collections have explored their holdings in remembrance of world-renowned mime artist Marcel Marceau and his experiences of the Holocaust.

Marceau was born in Strasbourg, France, on 22 March 1923. His birth name was Marcel Mangel and he was born to Jewish parents, as such, his life was dramatically changed by the German occupation of France during World War II, and the devastation that the Holocaust brought to millions of lives.

Shortly after the outbreak of war in September 1939, with Strasbourg being right on the French/German border, it was not safe for Jewish families to stay, in fact the whole city was evacuated. So, at the age of only 16, Marcel and his family were forced to leave their home. They travelled to Périguex in Dordorgne and, in 1941, moved to Limoges in the Périgord region of France.

In Limoges, along with his older brother Simon (to become known as Alain), he was urged by his cousin Georges Loinger to join the ‘Underground’, the French Jewish Resistance (Organisation Juive de Combat or Armée Juive), working with them between 1941-1943.

Marceau also predominantly worked with a charity that helped save Jewish refugee children, OSE – Oeuvre de secours aux enfants (BBC, 2023), making many trips with groups of children through the mountains. Marceau acknowledges that “I saved children, bringing them to the border in Switzerland. I forged identity cards with my brother when it was dangerous because you could be arrested if you were in the underground. I also forged papers, not to save only Jews, and children, but to save Gentiles …” (Marceau, 2002, p.116). The latter work was falsifying the ages of young, non-Jewish French men who would otherwise have been sent to work in factories or labour camps in Germany. During this period, he created a false identity and changed his surname to Marceau, after a General of the French Revolution whom Marcel had read about in a poem by Victor Hugo. It was not safe to reveal your real name or talk about your life before the war.

In 1944, his father Charles was arrested by the Gestapo, sent by convoy to Paris, then Dachau and eventually to Auschwitz concentration camp. Here he was killed, a victim of the Holocaust and the mass-scale murders carried out as part of the Nazi’s ‘Final Solution’; Marceau’s mother Chancia (Anne) survived the war. Marceau states that he not only cried for the loss of his father but for the millions who died (Marceau, 2002, p.118).

As a child, Marcel had a love of performing and had been inspired by music hall and by the stars of silent films such as Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy. He had also wanted to be an art student, and whilst in Limoges, managed to study some decorative arts and theatre at the Conservatoire there. Towards the end of the war, his cousin Georges, whom Marceau refers to as an “heroic Resistance fighter” (Marceau, 2002, p.116), sent him into hiding to protect him and save him for the important role Georges felt he would play in theatre after the war. He was hidden in an unconventional orphanage in Paris, where he was able to use his skills to teach children.

Two months before the liberation of France (in August/September 1944), he joined the renowned Charles Dullin’s School of Dramatic Art in Paris and studied with master of mime Étienne Decroux (Marceau, 2002). This was the foundation of his training as a mime artist. In November 1944, Marceau joined the French First Army of Occupation, travelling to Germany and working alongside American GIs of the allied troops. In Frankfurt he met a Captain Parker, and in a conversation about his future, he demonstrated some of his mime work and was asked to perform for the troops, his first big performance (BBC, 2023).

After the war he continued to study mime and acting and joined the theatrical company of Jean-Louis Barrault. Later, in 1947, he introduced to the world the character that would bring him fame and become his alter ego, ‘Bip the Clown’, with his white face based on Pierrot from Commedia dell’arte, stripy top and battered hat with a red flower.

Marceau refers to mime as ‘the art of silence’, a universal art which ‘speaks’ to everyone as there are no language barriers. “It is a complete art in the sense that it tends toward an all-embracing definition of the human being. A mime can come closest to identification with both human being and inanimate objects, and express the most carefully hidden feelings.” (Marceau, 1973, p.14). He felt that as destiny had spared him, “I have to bring hope to people who struggle in the world, and in my art I will bring dreams …” (Marceau, 2002, p.118). Although much of his work (known as mimodrama) did reflect light-hearted themes, it also contained metaphor and social and political commentary influenced by his own life experiences.

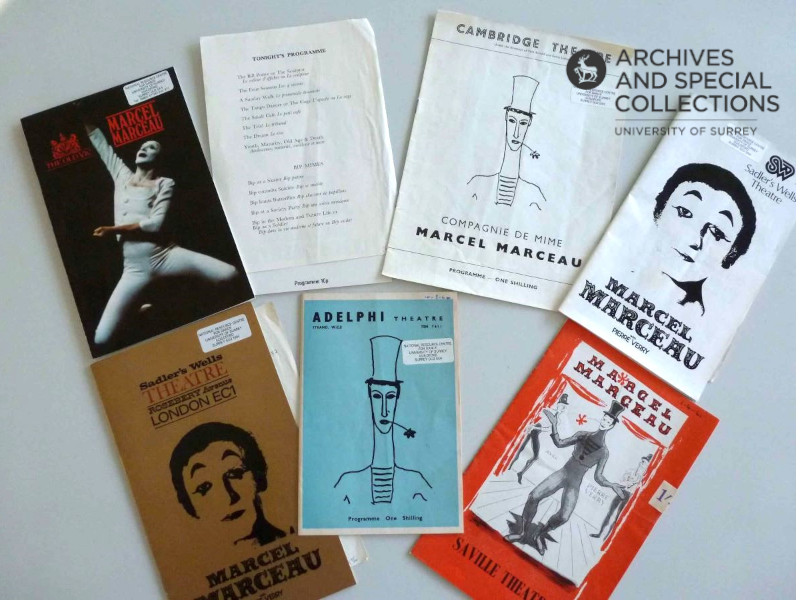

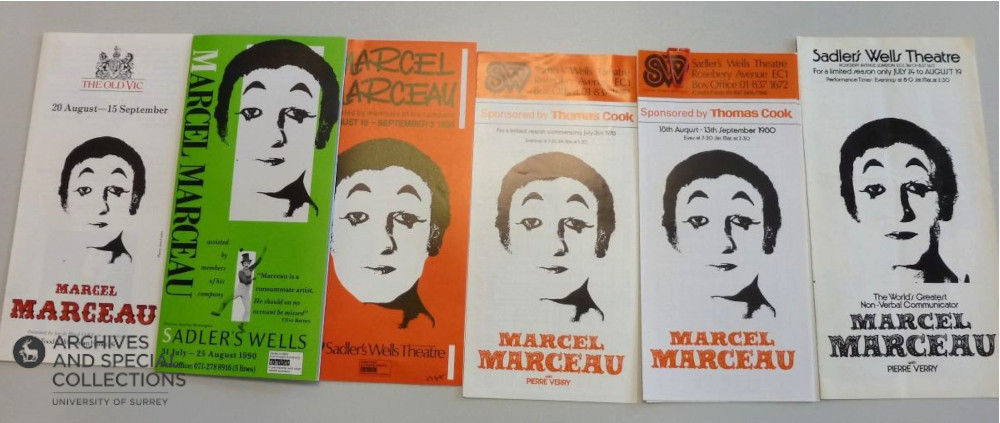

In our collections we hold a range of archive materials related to Marcel Marceau’s long career on the stage – more than 60 years! We have a couple of books which explore his contribution to his chosen artform, theatre programmes which detail performances, mainly in London, between 1957-1990, newspaper clippings which review many performances, and publicity materials promoting his shows.

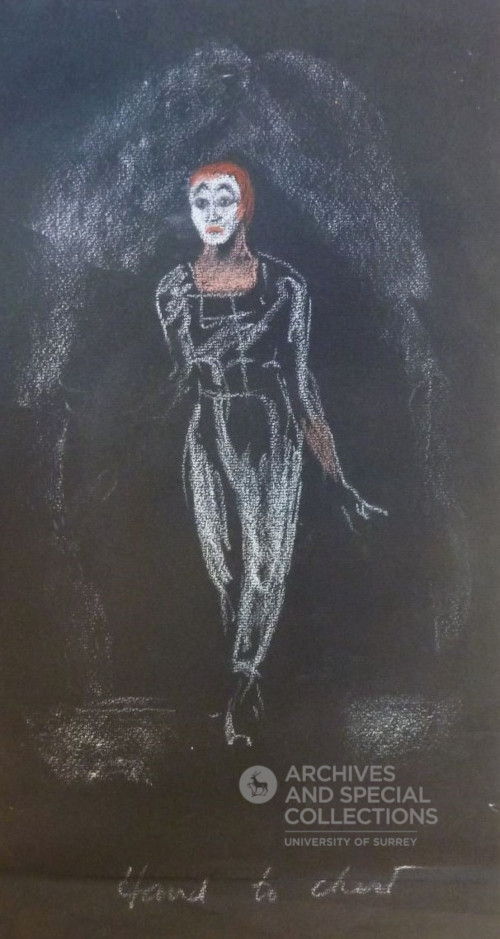

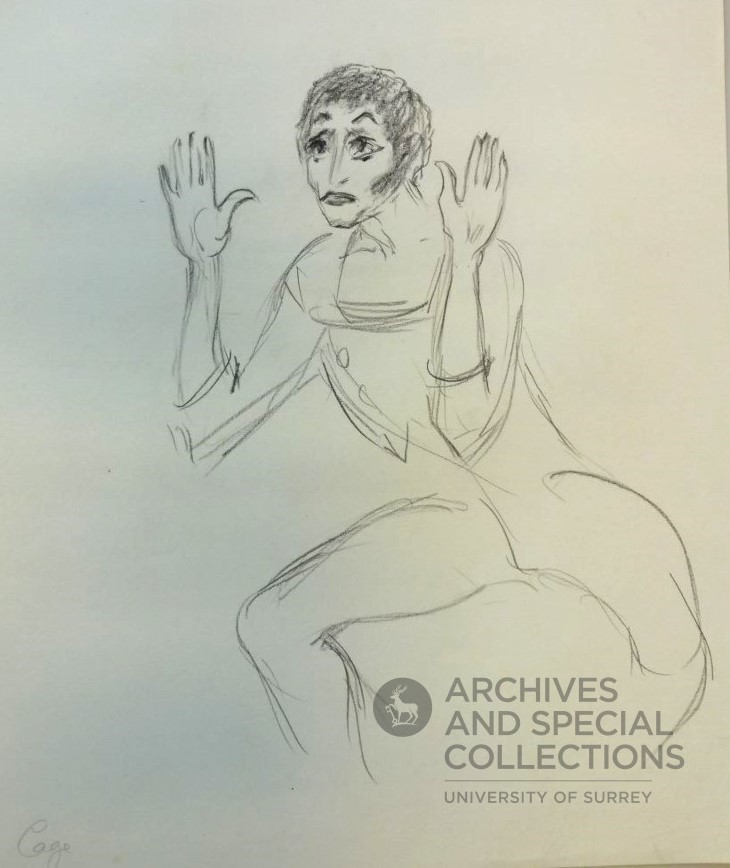

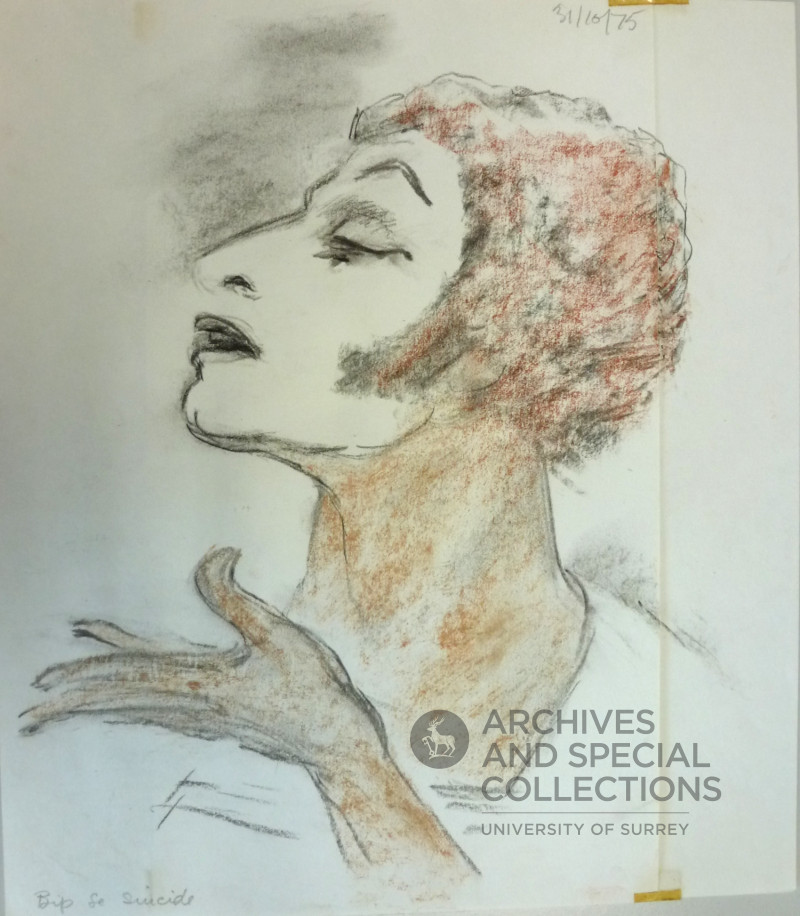

Perhaps the most interesting archive records we hold are original drawings by Australian artist Eilean Pearcey which are in the Eilean Pearcey Archive. Pearcey made England her home in 1931, she moved within dance and creative circles in London and became personal friends with many artists, including Marceau. Although yet to be catalogued, her portfolios contain many studies she created of Marceau from the early 1960s onwards; they are drawn in performance, or from the wings during rehearsals, or studies that she then worked up into more finished drawings. Here we show just a handful of those artworks which capture some of the essence of this celebrated mime artist.

Every year, the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust (HMDT) selects a theme for Holocaust Memorial Day and this year it is ‘Fragility of Freedom’. In connecting with this year’s theme, it is clear that, although Marcel Marceau evaded capture by the Nazis, survived the war and achieved great success in his life, he had faced many challenges to reach that eventual freedom. He was forced to flee his home at a young age, he was compelled to change his name and, thus, his identity, he faced great dangers in his work with the ‘underground’ risking his own freedom, indeed his life, to save others, he went into hiding, and he lost close family members and friends through the Holocaust. Despite all that he witnessed and lost at a young age, he wanted to bring joy, shared appreciation, common ground and understanding to the world through his work as a mime. In his speech upon receiving the Raoul Wallenberg Medal, Marceau concludes “The time in which we have no more wars, life will offer a real hope for the future.” (Marceau, 2002, p.119). A sentiment which still resonates in today’s world.

The National Moment – Light the Darkness

On Saturday 27 January at 20:00 GMT, everyone is invited to light a candle and safely place it in their window to:

- remember those who were murdered for who they were

- stand against prejudice and hatred today

We are all lighting the darkness on #HolocaustMemorialDay

Sources:

Dorcy, J. (1961) The Mime. New York: Robert Speller & Sons.

Fifield, W. (1968) ‘The Mime Speaks: Marcel Marceau’. The Kenyon Review, 30(2), pp. 155-165.

Marceau, M. (2002) ‘How I worked in the French resistance and created Bip as a figure of hope’. Michigan Quarterly Review, 41(1), Winter, pp. 114-119.

Marceau, M. (1973) ‘The Art of Silence’, Music Journal, 31(4), Apr 1, p.14.

Martin, B. (1978) Marcel Marceau, Master of Mime. Paddington Press.

Archive on 4: The Art of Silence. BBC Radio 4, 9 Dec 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001t988

Atamain, C. (2021) ‘Playing with the Truth: Jonathan Jakubowicz’s Resistance and the Memory of Marcel Marceau’. The Brooklyn Rail, June [online – see interview with Marceau’s daughter Camille]

Marceau, M. (1971) Marcel Marceau Speaks in English. USA: Caedmon Records. https://archive.org/details/lp_speaks-in-english_marcel-marceau/disc1/01.02.+The+Eternal+Law+Of+The+Underdog.mp3