By Diane Watt, University of Surrey

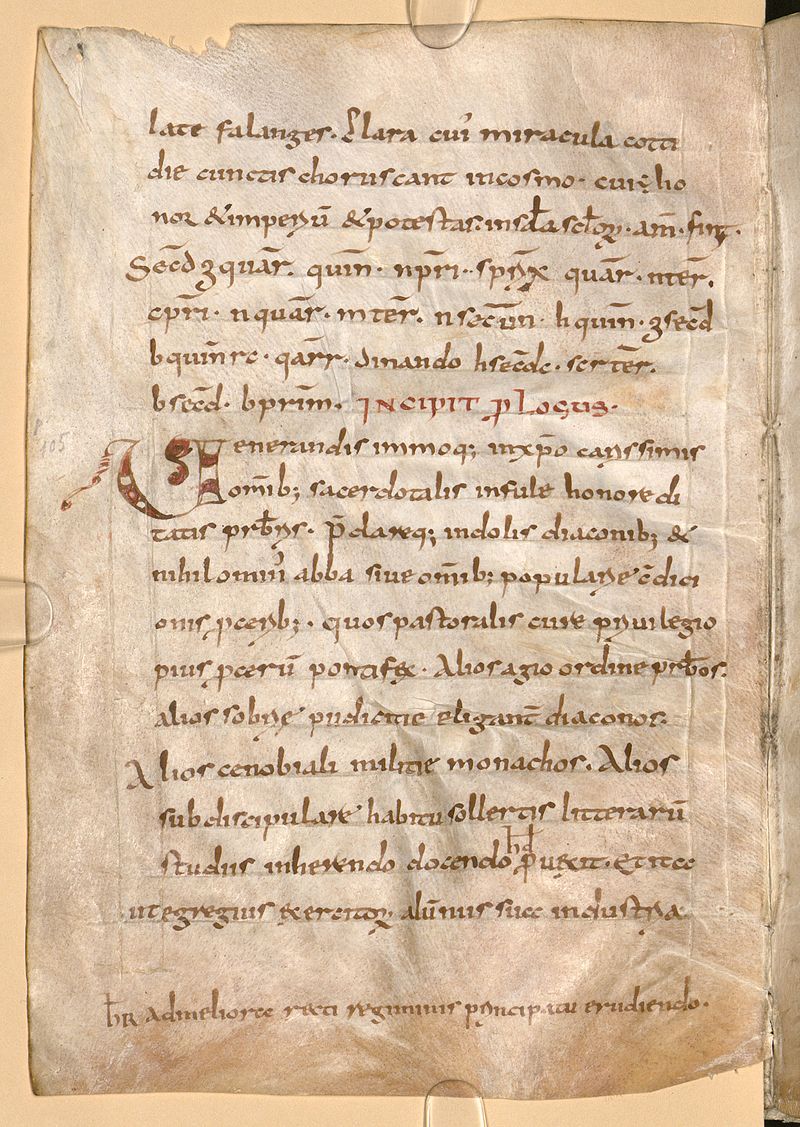

Hugeburc’s name is hidden in a cipher in Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Codex latinus monacensis (Clm) 1086, fol. 71v. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The project Women’s Literary History before the Conquest identifies early authors whose position as foremothers in the canon of English women’s writers has been overlooked for too long. Two of the most notable examples are Leoba (d.782), an Anglo-Saxon missionary in Francia, and Hugeburc (fl. 760–780), an Anglo-Saxon nun who joined the Benedictine monastery of Heidenheim. Leoba was a correspondent of St Boniface, and she sent him the first extant example of poetry that we know for certain was written by an English woman. Hugeburc, who wrote lives of the brothers St Willibald and St Winnebald, is the first named English woman writer of a full-length literary narrative.

The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek [The Bavarian State Library] in Munich contains manuscripts relating to these two women writers alongside a number of others, manuscripts that are then of great importance to women’s English literary history. The first of these is Codex latinus monacensis (Clm) 8112, which contains one of the earliest and most authoritative collections of the correspondence of Boniface and his circle. This version of the Boniface correspondence was produced in Mainz and dates to around 800.

Included in the Boniface correspondence is the only surviving letter from Leoba to Boniface, which was written in c.732 when Leoba was still a nun at Wimborne Abbey in what is now Dorset. This letter appears on folios 106r-106v of Clm 8112. In it Leoba introduces herself to Boniface, who was related to her through her mother, Æbbe. Her parents having died, Leoba describes herself as a woman who, in the absence of kinsmen, is isolated and vulnerable.

It is in this letter that the example of Leoba’s poetry is found, although the first of the four lines of verse that follow the valediction in the Vienna Boniface Codex (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Lat. Vindobonensis 751) at fols.21r-21v is missing in Clm 8112.

Vale, vivens aevo longiore, vita feliciore, interpellans pro me.

Arbiter omnipotens, solus qui cuncta creavit,

In regno patris semper qui lumine fulget,

Qua iugiter flagrans sic regnat gloria Christi,

Inlesum servet semper te iure perenni.

[Farewell, and may you live long and happily, making intercession for me.

The omnipotent Ruler who alone created everything,

He who shines in splendor forever in His Father’s kingdom,

The perpetual fire by which the glory of Christ reigns,

May preserve you forever in perennial right.]

While some previous critics have dismissed these lines of verse as derivative, the short poem needs to be read as integral to Leoba’s letter as a whole. Leoba seeks to establish an enduring relationship with Boniface, which, if it does not place them on equal footing, certainly invites him to act as her spiritual protector. The closing prayer also effectively places Boniface in Leoba’s debt. The tone is not plaintive but assertive.

Leoba went on to join Boniface’s mission in Francia and to become abbess of Tauberbischofsheim. Her remarkable biography was recorded by Rudolf of Fulda in his Life of Leoba, which was written in c.836, over 50 years after her death . It is perhaps surprising that members of Leoba’s own community did not compose her hagiography, especially given that Tauberbischofsheim probably had its own scriptorium. However Leoba had strong personal ties to Fulda, which was a major centre of learning and monastic book production. Furthermore Rudolf states in his prologue that his text based at least in part on the mediated memoirs of four nuns, Agatha, Thecla, Nana and Eoloba. Indeed it seems likely that Leoba herself must have been the ultimate source of much of the material included within the text.

From the outset it is clear that Rudolf of Fulda’s Life of Leoba was produced within the milieu of a thriving literary culture centred on women. The earliest copy, also now located in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, is Clm 18897, fols. 3r-43v, and it dates to the tenth century. Another later manuscript witness, dating to the late eleventh-century and again held in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, is Clm 11321, fols. 101r-120r. This manuscript is significant because on fols.101r-101v it is dedicated to another abbess, Hadamout, usually identified as Hathumod of Gandersheim (c.840-874). She is instructed to read the text for profit—she must seek to emulate Leoba in her own life—but also for her own pleasure. As Hathumod was not born when Rudolf completed the Life, this dedication must have been added by him some years later, and he goes on to extend the intended audience to include the entire community of nuns.

The religious house at Heidenheim, where Hugeburc was a nun, was founded by St Winnebald in 752. Walburg, sister of Willibald and Winnebald, became abbess following Winnebald’s death in 761, and at that point it became a double monastery, the only one outside of England. Hugeburc joined at the same time. Hugeburc was related to this powerful missionary family and was deeply personally invested in her hagiographical writings.

One of Hugeburc’s two biographical works is the Hodoeporicon or voyage narrative of St Willibald. It offers an account of the saint’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the 730s that is closely based on his own account, which he dictated to Hugeburc some forty years later (in 778). Elsewhere, I have suggested that Hugeburc’s narrative reads like an early guidebook, full of practical details and information about place to visit and sights to be seen, and that within it Hugeburc creatively reimagines a journey that she may well have wished she could have undertaken herself.

Hugeburc introduces herself at the start of this text as an indigna Saxonica [unworthy Saxon Woman] (‘Vita Willibaldi’, 86; translation my own) apparently deflecting attention away from herself as author and writer. She asserts that she is motivated to write by a desire to preserve the memory of Willibald for posterity and she goes onto apologize because, as she says, she is ‘feminea fragilique sexus inbecillitate corruptibilia, nulla prerogativa sapientiae suffultus aut magnarum virium industria elata’ [corruptible by the feminine frailty of the fragile sex, neither supported by the prerogative of wisdom nor elevated by the industry of great strength] (‘Vita Willibaldi’, 86; translation my own).

Yet there is something of an inevitable paradox in Hugeburc’s adoption of the humility topos, because even as she directs her readers away from herself, she makes them very aware of her identity: a female religious from a saintly Saxon family. And indeed within the text, on folio 71v of the earliest surviving manuscript, Clm 1086, which dates to the early ninth century (also held in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek), she encrypts her own name (for an explanation of the cryptogram, see this blog post by Thijs Porck).

Unencrypted, the Latin reads:

Ego una Saxonica nomine Hugeburc ordinando hec scribebam

[I, a Saxon nun named Hugeburc, wrote this]

(translation my own)

Hugeburc thus ensures that, like the narrative she recounts, her name will also be preserved for posterity. Her role as writer is acknowledged even as it is disguised and hidden. Hugeburc, it seems, hoped that future generations at least would remember who she was and what she had achieved.

In Leoba’s letter and Hugeburc’s hagiographies we find crucially important early examples of Anglo-Saxon women’s writing in prose and poetry, albeit in codices preserved only in modern day Germany. Leoba may well also have had considerable, if indirect, input into Rudolf of Fulda’s account of her life. These texts and the manuscripts in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich are then absolutely central to English women’s literary history.